Diffusion

1Department of Radiology, Stanford University, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Contrast mechanisms: Diffusion

Diffusion weighted MRI (DWI) and diffusion-tensor MRI (DTI) are MRI techniques that enable measuring the self-diffusion of water molecules in soft tissues. DWI and DTI methods enable quantitative estimates of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) or mean diffusivity (MD), fractional anisotropy (FA), fastest direction of diffusion (eigenvectors and tracts), and more. DWI and DTI measures are uniquely sensitive to tissue orientation and organization and provide insight to tissue changes that accord with edema, anisotropy, cellularity, and more. DWI and DTI are powerful research and diagnostic clinical tools with applications in the brain, body (abdominal), chest, muscles, prostate, breasts, and beyond.Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) first emerged as a remarkable diagnostic imaging tool capable of soft-tissue contrast attributed to relative differences in tissue relaxation properties (i.e., $$$T_1$$$ and $$$T_2$$$). During the subsequent decades, substantial improvements in MRI hardware (e.g., stronger and more homogenous main fields, higher performance gradient systems, multi-channel receiver systems) coupled with profound advances in data sampling and image reconstruction theory have resulted in MRI becoming established as an essential diagnostic imaging tool in radiology and other medical specialties. A key contribution to both the research and clinical impact of MRI was the development of “diffusion weighted MRI” (DWI) methods made sensitive to the self-diffusion of water molecules in soft-tissues [1]. Later, the work of Basser et al. [2] demonstrated that the MRI signal is directionally dependent on the tissue-level diffusion anisotropy, thus giving rise to “diffusion tensor MRI” (DTI or DT-MRI). Both DWI and DTI enable the quantitative assessment of several tissue microstructural properties related to the self-diffusion of water. The remarkable ability to non-invasively probe tissue diffusion with DTI has captured the attention of neuroscientists, neurologist, psychiatrists, and neurosurgeons owing to the unrivaled ability to probe brain anatomy and microstructure [3]. Beyond that, DWI and DTI have emerged as important methods with research and diagnostic applications in body (abdominal), thoracic, musculoskeletal, breast imaging, and beyond [4].Theory

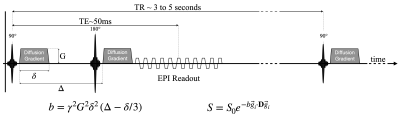

Several papers review the basic theory of DWI and DTI [5]. Water molecules are thermally driven to undergo Brownian motion and consequently they “randomly walk” in accordance with the surrounding tissue microstructure that governs the local diffusion coefficient ($$$D>0$$$). The diffusion tensor ($$$\mathbf{D}$$$) is a simple model used to characterize the intravoxel diffusive process. $$$\mathbf{D}$$$ can be thought of as a 3x3 matrix (rank-2, symmetric) representation of the underlying diffusive process that can be decomposed into a system of eigenvectors ($$$\vec{e}_i$$$, principal directions of diffusion) and eigenvalues ($$$\lambda_i$$$, principal magnitudes of diffusion). The magnitude of diffusion is not directionally dependent for isotropic tissues, but it is directionally dependent for anisotropic tissues. If diffusion is anisotropic, then there is one fastest direction ($$$\vec{e}_1$$$, primary eigenvector) that accords with the fast magnitude of diffusion ($$$\lambda_i$$$, primary eigenvalue). This primary direction of diffusion accords with the elongated direction of many cell types, thereby providing an imaging-based method to probe the orientation and organization of soft tissues. Tensor invariants are another way to describe and extract information from $$$\mathbf{D}$$$. For example, mean diffusivity (MD$$$=trace$$$\mathbf{D}) estimates the average intravoxel diffusivity and is bound on $$$\left\{0, D_{H_2O}= 0.00308 mm^2/s \right\}$$$; and fractional anisotropy (FA) is related to the eigenvalue variance and estimates the magnitude of anisotropy where $$$FA=0$$$ is isotropic and $$$FA=1$$$ is anisotropic [6]. MD increases with a loss of diffusive barriers. FA increases when diffusive barriers are organized to restrict diffusion more (or less) in one direction. The MRI signal’s sensitivity to the self-diffusion of water molecules in soft-tissues arises from the application of “diffusion gradients” (Fig. 1). Diffusion gradients are usually applied on either side of the refocusing pulse found in a spin echo sequence; and the magnetization is sampled with an echo planar imaging (EPI) readout. The diffusion gradients have an area large enough to impart an intravoxel phase dispersion. In theory, if the water molecules do not move ($$$\mathbf{D}=0$$$), then the second diffusion gradient lobe perfectly rewinds the phase imparted by the first diffusion gradient lobe. In general, however, water molecules are thermally driven to undergo Brownian motion and consequently they “randomly walk” and the resultant phase distribution can be estimated as zero-mean Gaussian distributed with a phase variance $$$<\phi^2>$$$. A non-zero phase variance implies an intravoxel phase dispersion ($$$<\phi^2>$$$) that gives rise to an intravoxel signal drop ($$$S<S_0$$$) that is exponentially proportional to the rate of diffusion ($$$D$$$) and a measure of the diffusion gradient magnitude termed the b-value ($$$b$$$) according to: $$S=S_0e^{-<\phi^2>}=S_0 e^{-bD}, Eqn. 1$$ Therein, $$$S$$$ is the measured DWI signal and $$$S_0$$$ is the non-DWI signal (acquired without diffusion encoding gradients or b=0). The b-value (typically 500 to 1000 $$$s/mm^2$$$) summarizes the magnitude of the diffusion encoding gradients and considers the gradient magnitude ($$$G$$$), duration ($$$\delta$$$), and separation ($$$Delta$$$), Fig. 1. For rectangular gradients (i.e., ignoring gradient slewing) the b-value is defined as: $$$b=\gamma^2 G^2 \delta^2 \left(\Delta - \delta/3 \right)$$$. Typically, estimating $$$D$$$ is of greatest interest and Eqn. 1 is used to solve for $$$D$$$ from two measurements ($$$S$$$ and $$$S_0$$$) obtained with a programmed b-value. The extension of Eqn. 1 to obtain estimates of the diffusion tensor ($$$\mathbf{D}$$$) is aided by recognizing that Eqn. 1 samples a projection of the underlying tissue’s diffusion tensor process along the direction of the applied diffusion encoding gradients ($$$\vec{g}$$$). Owing to the need to estimate the six unique diffusion tensor components, plus a reference image, acquired without diffusion gradients applied ($$$S_0$$$), a total of seven signal estimates are required to quantify $$$\mathbf{D}$$$ from: $$S=S_0 e^{-b \vec{g}_i \cdot \mathbf{D} \vec{g}_i }, Eqn. 2$$ The methods used to acquire these signals (i.e., images) are described in the following section.Methods

Protocols for acquiring DWI and DTI varying widely and depend on the available pulse sequences, hardware, anatomic location (i.e., organ), and acceptable scan times.Pulse Sequences – The majority of DWI and DTI data are acquired with single-shot EPI because it is very fast. Multi-shot methods are possible, but require more advanced approaches to mitigate complex phase discrepancies between shots that arise from bulk motion of the subject [7]. In general, the TE is minimized (typically ~50 ms for $$$b\approx500s/mm^2$$$ to 80 ms for $$$b\approx1000s/mm^2$$$) and the TR is several seconds to allow for signal recovery, which readily permits slice/slab interleaved acquisitions and/or respiratory motion management. EPI acquisitions are distorted owing to off-resonance and various methods are employed to limit this distortion [8]. Simultaneous multi-slice/slab imaging can be used to further accelerate image acquisition [8]. The targeted spatial resolution depends on the imaging goal but is typically <2.5 mm in-plane. Thin slices (<5 mm) are also preferred. The choice of b-value depends on the permissible signal attenuation and underlying bulk motion. Higher b-values (≥1000 $$$s/mm^2$$$) are used in the brain and central nervous system, but lower b-values are used elsewhere (e.g., ~500 $$$s/mm^2$$$ for the abdomen). Given the inherently lower SNR of DTI acquisitions, it may be important to obtain signal averages, but it is also possible to improve image quality by obtaining >6 diffusion encoding directions, thereby overdetermining the system of equations needed to estimate $$$\mathbf{D}$$$. In general, the trade-off between the number of averages and the number of directions to obtain (for a fixed amount of scan time) is best summarized as obtaining enough signal averaging to be above the noise floor, then increase the number of directions up to the limit of allowable scan time [10].

Hardware – DWI and DTI both benefit from higher field imaging ($$$>3 T$$$ for more inherent signal) because they are inherently signal attenuated sequences. High performance gradient hardware ($$$>50 mT/m$$$ and $$$150-200 T/m/s$$$) also permits shorter diffusion encoding gradients and minimum echo spacing. Together this minimizes the echo time (TE) and maximizes the available signal while mitigating off-resonance distortion. Receiver coils with 16 or more channels enables accelerated imaging by way of parallel imaging, which also helps limits off-resonance distortion and reduces scan time.

Anatomic Location – As with most MRI techniques, specific protocols depend on the anatomical location of interest [11-13]. Patient motion, respiratory motion, and cardiac pulsatility can all impact the quality of DWI/DTI. Both DWI and DTI are very motion sensitive, and any underlying motion can contribute significant artifactual signal attenuation. This can, for example, lead to estimates of ADC or MD that exceed that of free water (one way to confirm data quality) or produce FA values that exceed the interval [0,1], owing to unrealistic negative eigenvalues. When the location is relatively stationary (e.g., brain and musculoskeletal) higher b-values provide the diffusion sensitivity and longer scan times may be tolerated, which permits acquiring higher spatial resolution. When imaging the chest or abdomen respiratory motion must be managed with breath holding, respiratory gating, or navigators. Lower b-values are also used to limit bulk motion artifacts, preserve SNR, and limit susceptibility artifacts with lower TEs.

Challenges and Future Outlook

Challenges – Diffusion imaging faces several challenges for which numerous approaches have been developed. Acquisition speed remains a challenge as it does for most MRI methods. Managing image artifacts that arise from off-resonance (distortion), eddy currents (distortion), bulk patient motion (mis-registered images), and respiratory and cardiac motion (signal drop out) are also persistent challenges. Increasing emphasis is now being placed on quantitative accuracy, defining normal values across a range of anatomies and pathologies, and reconciling subtle differences in measured values within and between MRI platforms [14-15]. There is also a lot of emphasis on estimating increasingly specific diffusion-based tissue biomarkers (e.g., cellularity, axon diameter, etc.) with more complex acquisition and signal modeling approaches [16,17].Future Outlook – For those interested in furthering their understanding of emerging methods in DWI and DTI the following references are recommended: advanced diffusion encoding, advanced DWI and DTI acquisitions, advanced DWI and DTI image reconstruction [18].

Acknowledgements

I'm grateful for the collaborations I have with many faculty, research scientists, postdocs, graduate students, and undergraduate students. Many thanks also to those with whom I have the great pleasure of discussing MRI!References

1. Stejskal, Edward O., and John E. Tanner. "Spin diffusion measurements: spin echoes in the presence of a time‐dependent field gradient." The journal of chemical physics42.1 (1965): 288-292.

2. Basser, Peter J., James Mattiello, and Denis LeBihan. "MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging." Biophysical journal 66.1 (1994): 259-267.

3. Assaf, Yaniv, and Ofer Pasternak. "Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-based white matter mapping in brain research: a review." Journal of molecular neuroscience 34 (2008): 51-61.

4. Dietrich, Olaf, et al. "Technical aspects of MR diffusion imaging of the body." European journal of radiology 76.3 (2010): 314-322.

5. Basser, Peter J., and Derek K. Jones. "Diffusion‐tensor MRI: theory, experimental design and data analysis–a technical review." NMR in Biomedicine: An International Journal Devoted to the Development and Application of Magnetic Resonance In Vivo 15.7‐8 (2002): 456-467.

6. Ennis, Daniel B., and Gordon Kindlmann. "Orthogonal tensor invariants and the analysis of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance images." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 55.1 (2006): 136-146.

7. Runge, Val M., and Johannes T. Heverhagen. "Multishot EPI." The Physics of Clinical MR Taught Through Images. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022. 144-145.

8. Wu, Wenchuan, and Karla L. Miller. "Image formation in diffusion MRI: a review of recent technical developments." Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 46.3 (2017): 646-662.

9. Setsompop, Kawin, et al. "Improving diffusion MRI using simultaneous multi-slice echo planar imaging." Neuroimage63.1 (2012): 569-580.

10. Jones, Derek K., Mark A. Horsfield, and Andrew Simmons. "Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 42.3 (1999): 515-525.

11. Iima, Mami, et al. "Diffusion MRI of the breast: Current status and future directions." Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 52.1 (2020): 70-90.

12. Smith, Seth A., James J. Pekar, and Peter CM Van Zijl. "Advanced MRI strategies for assessing spinal cord injury." Handbook of clinical neurology 109 (2012): 85-101.

13. Ni, Ping, et al. "Technical advancements and protocol optimization of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in liver." Abdominal Radiology 41 (2016): 189-202.

14. Shukla‐Dave, Amita, et al. "Quantitative imaging biomarkers alliance (QIBA) recommendations for improved precision of DWI and DCE‐MRI derived biomarkers in multicenter oncology trials." Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 49.7 (2019): e101-e121.

15. Schmeel, Frederic Carsten. "Variability in quantitative diffusion-weighted MR imaging (DWI) across different scanners and imaging sites: is there a potential consensus that can help reducing the limits of expected bias?." European radiology 29 (2019): 2243-2245.

16. Hayashida, Y., et al. "Diffusion-weighted imaging of metastatic brain tumors: comparison with histologic type and tumor cellularity." American journal of neuroradiology 27.7 (2006): 1419-1425.

17. Assaf, Yaniv, et al. "AxCaliber: a method for measuring axon diameter distribution from diffusion MRI." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 59.6 (2008): 1347-1354.

18. Topgaard, Daniel, ed. Advanced diffusion encoding methods in MRI. Vol. 24. Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020.

Figures