Inflammatory Basis of Neurological Diseases II: Cerebrovascular, Neurodegenerative & Neuropsychiatric Disorders

1INSERM U1237 - Normandie University, Caen, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro: Cerebrovascular, Cross-organ: Inflammation, Contrast mechanisms: Molecular imaging

Inflammation is a hallmark of most neurological disorders. Following perturbation of the homeostasis of the central nervous system, both innate and adaptive immune systems are at play to limit the extent of diseases and mediate repair and regeneration. Yet, abnormal activation of the immune system in the brain can worsen brain damages and influence cognitive functions. The pathophysiological mechanisms driving neuroinflammation in the context of cerebrovascular, neurodegenerative, and neuropsychiatric disorders are similar and offer interesting biomarkers for imaging.Leukocyte diapedesis is triggered by a cascade of pro-inflammatory events: after CNS damage, resident brain cells (mainly astrocytes and microglia) release inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1-β, which activate the endothelium and lead to the luminal expression of selectins and adhesion molecules. This activated endothelium supports the adhesion of circulating leukocytes that are attracted by the gradient of chemokines originating from the CNS. Lastly, leukocytes egress from the blood into the brain to participate in the neuroinflammatory reaction1.

The roles of cerebral endothelial cells during the CNS inflammatory response, the related signaling pathways, and the crosstalk between cerebral endothelial cells and immune resident CNS cells are key to this process2. Microglia are resident immune cells of the CNS that belong to the population of primary innate immune cells. Microglia operate as safeguards of the CNS, scanning the environment for danger cues and/or invading pathogens: being regularly distributed throughout the CNS, like watchmen, they undergo activation by local danger cues. Microglia actively adapt cell morphology in response to these signals, by increasing soma size and retracting their thin cytoplasmic processes. The activation of microglia is overall protective for the brain. However, sustained or chronic activation of microglia can lead to irreversible CNS damage. Indeed, persistent inflammation in the brain affects neuronal plasticity, impairs memory, and is generally considered a typical driver of tissue damage in neurovascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Comparing microglia signature in neuroinflammatory vs. neurodegenerative disorders suggests the existence of subsets of activated microglia – that can be defined by common cell surface markers – expressing heterogeneous cytokines that might contribute to the tissue damage versus repair in different ways. Moreover, activated microglial cells are considered potential specific biomarkers of neuroinflammation. As part of the neurovascular unit, microglial cells play a role in the crosstalk between the CNS and the rest of the body through activation of the cerebrovasculature.

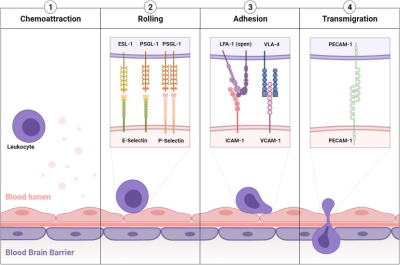

Under physiological conditions, the vascular endothelium of the CNS is in a quiescent state characterized by a limited interaction with circulating leukocytes. Accordingly, adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule I (ICAM-1), E-selectin and P-selectin are expressed in only trace amounts at the extracellular surface of the endothelial microvasculature. Upon injury, the endothelial cells shift from a quiescent to an activated phenotype, involving increased vascular permeability, switch to a pro-thrombotic state, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and exposure of adhesion molecules (Figure 1)1,2.

According to current knowledge, endothelial activation can be divided into type I and type II. Type I is characterized by an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration typically driven by G-protein coupled receptor activation. This transient elevation in Ca2+ triggers the exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies (small, preformed intracytoplasmic vesicles containing essentially two proteins, von-Willebrand Factor and P-selectin) and induces the addressing of P-Selectin to the endothelial surface, which contributes to leukocyte binding on the vessel wall. Interestingly, the CNS vasculature presents a specific regulation of P-selectin expression, that was proposed to be independent on Weibel-Palade bodies, thus suggesting that the role of P-selectin is different in the cerebrovasculature and in other vascular beds. Type II activation of endothelial cells is a more sustained inflammatory response induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is characterized by an increased transcription and protein synthesis of cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules. In particular, type II activated endothelial cells present high expression levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin. Once engaged, leukocyte transmigration requires platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1), which is expressed in endothelial cell intercellular junctions. P- and E-selectin are mainly involved in the initial recruitment of leukocytes (rolling) whereas ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are mainly involved in firm leukocyte adhesion. The main ligands of both P- and E-selectins are P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) and sialylated carbohydrates, which are present on the surface of neutrophils, monocytes, platelets, eosinophils and some lymphocyte subtypes. Ligand selectivity and vascular bed expression profiles of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 explain their differential roles: the main ligands of ICAM-1 are macrophage adhesion ligand-1 (Mac-1) and leukocyte associated antigen-1 (LFA-1), whereas the main ligand of VCAM-1 is very late antigen-4 (VLA-4). According to the expression profile of VLA-4, VCAM-1 is mainly involved in the diapedesis of lymphocytes, monocytes and eosinophils. Importantly, LFA-1 and VLA-4 are integrins that require a change in their conformation to acquire high affinity for ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, a process triggered by an increase in cytosolic Ca2+. As a result, only activated leukocytes can bind ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. PECAM-1 has both homophilic (binding with itself) and heterophilic ligands. Except for PECAM-1 (which is not reachable by large contrast carrying particles), all these proteins, which are differentially expressed by activated and quiescent endothelial cells, are potential targets for molecular MRI of neuroinflammation1,3.

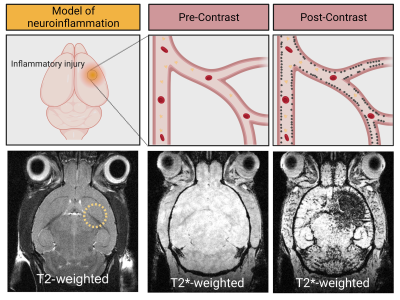

The feasibility to reveal and measure cerebral endothelial activation has been demonstrated using Micro-sized Particles of Iron Oxide (MPIO) targeted to adhesion molecules (Figure 2)4. Since the seminal study introducing the use of MPIO for molecular MRI, numerous studies have confirmed the viability of this method and demonstrated its application for early diagnosis, detection of subclinical injury, monitoring of therapeutic response and grading of the severity of CNS disorders (Figure 3)4-7.

Acknowledgements

Illustrations were created with BioRender.comReferences

1. M. Gauberti, A. P. Fournier, F. Docagne, D. Vivien, S. Martinez de Lizarrondo, Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endothelial activation in the central nervous system. Theranostics 8, 1195–1212 (2018).

2. M. Gauberti, A. Montagne, A. Quenault, D. Vivien, Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of brain-immune interactions. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8, 389 (2014).

3. J. Lohrke, T. Frenzel, J. Endrikat, F. C. Alves, T. M. Grist, M. Law, J. M. Lee, T. Leiner, K.-C. Li, K. Nikolaou, M. R. Prince, H. H. Schild, J. C. Weinreb, K. Yoshikawa, H. Pietsch, 25 years of contrast-enhanced MRI: Developments, current challenges and future perspectives. Adv. Ther. 33, 1–28 (2016).

4. M. A. McAteer, N. R. Sibson, C. von Zur Muhlen, J. E. Schneider, A. S. Lowe, N. Warrick, K. M. Channon, D. C. Anthony, R. P. Choudhury, In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of acute brain inflammation using microparticles of iron oxide. Nat. Med. 13, 1253–1258 (2007).

5. A. Montagne, M. Gauberti, R. Macrez, A. Jullienne, A. Briens, J. S. Raynaud, G. Louin, A. Buisson, B. Haelewyn, F. Docagne, G. Defer, D. Vivien, E. Maubert, Ultra-sensitive molecular MRI of cerebrovascular cell activation enables early detection of chronic central nervous system disorders. Neuroimage 63, 760–770 (2012).

6. Martinez de Lizarrondo S, Jacqmarcq C, Naveau M, Navarro-Oviedo M, Pedron S, Adam A, Freis B, Allouche S, Goux D, Razafindrakoto S, Gazeau F, Mertz D, Vivien D, Bonnard T, Gauberti M. Tracking the immune response by MRI using biodegradable and ultrasensitive microprobes. Sci Adv. 2022 Jul 15;8(28):eabm3596.

7. Gauberti M, Martinez de Lizarrondo S. Molecular MRI of Neuroinflammation: Time to Overcome the Translational Roadblock. Neuroscience. 2021 Oct 15;474:30-36.

Figures