5436

Antiretroviral therapy use is associated with ectopic pericardial and paracardiac adipose deposition in people living with HIV1Division of Biomedical Engineering,Department of Human Biology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2Cape Universities Body Imaging Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 3South African Medical Research Council Extramural Unit on Intersection of Noncommunicable Diseases and Infectious Diseases, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 4Cape Heart Institute Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 5Division of Cardiology Department of Medicine, Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa, 6Faculty of Health and Wellness Sciences, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa, 7Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute and Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States, 8Charite University and Noninvasive Cardiac Imaging, Klinik und Poliklinik fur Kardiolgie und Nephrologie, Charite University, Berlin, Germany, 9Metabolism Unit, Endocrine Division, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 10Division of Cardiology and Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

Synopsis

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality in people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV). In the general population, increased pericardiac adipose tissue is associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes, but its role in HIV-associated CVD is not well described. Using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR), we report increased pericardial adipose tissue (PAT) and paracardiac adipose tissue (ParaAT) in PLHIV on ART compared to uninfected controls, with untreated PLHIV having an intermediate phenotype. For PLHIV not on ART, myocardial inflammation is associated with more significant impairment in strain and tissue characteristics, but not PAT and ParaAT volume.

Background

There are approximately 8.2 million people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) infection in South Africa. The widescale availability and use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically decreased the number of HIV/AIDS-related deaths and improved quality of life1,2,3; however, ART may also be associated with development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In particular, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, myocardial inflammation, myocardial fibrosis, and myocardial steatosis are common phenotypes in ART-treated PLHIV4.Hypothesis

We hypothesised that PLHIV on ART would exhibit lipodystrophy and excess ectopic pericardial adipose tissue (PAT) and paracardiac adipose tissue (ParaAT) deposition associated with adverse cardiovascular remodeling.Purpose

The aims of this study were two-fold: (1) to quantify, using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR), PAT and ParaAT in ART-treated and untreated PLHIV and matched controls without HIV; and (2) to investigate the relationship of PAT and ParaAT volume to HIV disease duration, ART regimen, and myocardial phenotypes of ventricular function, deformational characteristics, inflammation, and fibrosis.Methods

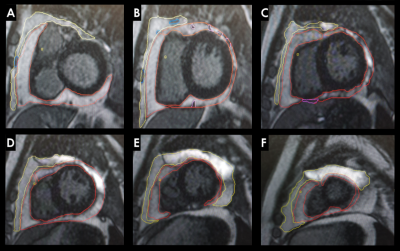

We employed a cross-sectional study design including 3 groups of participants: (1) PLHIV on ART; (2) untreated PLHIV; and (3) matched uninfected controls that were drawn from SA-CMR registry database, who were matched for age, sex, and ethnicity. CMR was performed on a Siemens Magnetom Skyra 3Tesla between February 2017 and March 2020. Images were postprocessed and analysed with proprietary software from Circle Cardiovascular Imaging (CVI)42®. PAT and ParaAT volumes were obtained by Simpson’s method, by manually contouring the borders of PAT and the ParaAT with regions of interest at end-diastole, from base to the apex of the heart5 (Figure 1). To differentiate pericardial effusion from PAT, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images acquired with a phase-sensitive inversion-recovery sequence were used. PAT and ParaAT volumes from different short-axis slices (8mm thickness) were summed to obtain whole-heart PAT and ParaAT volumes. Left (LV) and right (RV) ventricular volumes, LV mass (LVM), and function, T2 short Tau inversion-recovery imaging, strain and strain rates, T1 and T2 mapping, LGE, and extracellular volume (ECV) were also assessed.Results

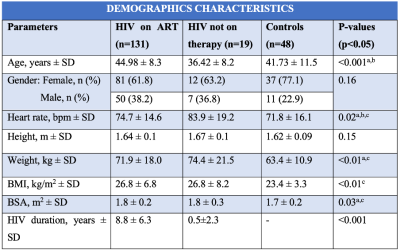

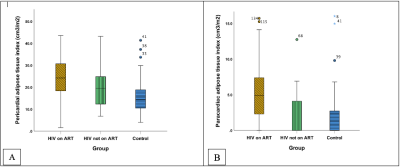

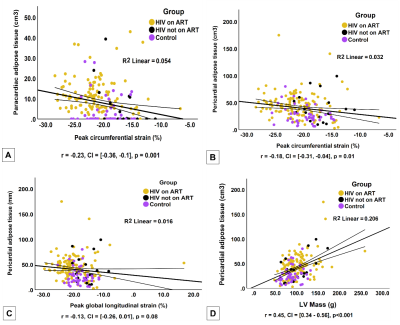

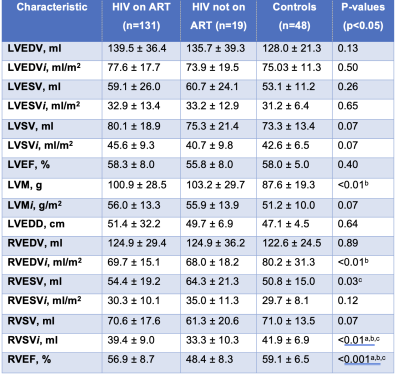

198 participants were included: PLHIV on ART (n=131), PLHIV naïve to ART (n=19), and matched uninfected controls (n=48). PLHIV on ART were older (44.9±8.3 years) than untreated PLHIV (36.4±8.2 years) and uninfected controls (41.7±11.5 years), respectively (p<0.001). A large distribution of our study cohort was female (Table 1). PLHIV on ART were on antiretroviral combination therapy treatment including nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor and protease inhibitor. PLHIV on ART had greater whole-heart PAT volumes 43.1cm3 (30.7-54.8 IQR) compared to untreated PLHIV 32.1 cm3 (22.8-52.8 IQR) or uninfected controls 22.99 cm3 (17.2-31.7 IQR), p<0.001. PLHIV on ART had higher whole-heart ParaAT volume 9.0 cm3 (3.8-13.4 IQR) compared to untreated PLHIV 0 cm3 (0.0-10.8 IQR) or uninfected controls 0 cm3 (0.0-5.2 IQR), p<0.001 (Figure 2). PLHIV on ART (100.9±28.5 g) and untreated PLHIV (103.2±29.7 g) had elevated LVM compared to uninfected controls (87.6 ± 19.3g), p<0.01 (Table 2). Untreated PLHIV had higher T1, T2 times and ECV (1301±58 ms; 42±4 ms; 32±5%) compared to PLHIV on ART (1251±47 ms; 39±3 ms; 31±5%) and uninfected controls (1224±48 ms; 39±2 ms; 29±9%), respectively. Similarly, untreated PLHIV had the largest burden of LGE and the greatest impairments in myocardial strain and strain rates. On univariate regression analysis in the pooled population, ParaAT demonstrated weak negative correlation with peak global circumferential strain (r=-0.23, p<0.001) and longitudinal strain (r=-0.21, p<0.01), while PAT showed a weak negative correlation with peak circumferential strain (r=-0.18, p<0.01) and moderate positive correlation with LVM (r=0.45, p<0.001) (Figure 3).Discussion

We demonstrate a gradient of PAT and ParaAT volume, which is greatest in PLHIV on ART, has an intermediate phenotype in untreated PLHIV, and is lowest in HIV uninfected persons. Abnormalities in strain, strain rate, LVM, myocardial inflammation and fibrosis are commonest in untreated PLHIV compared to PLHIV on ART and uninfected controls. Both PAT and ParaAT showed weak correlations with indices of myocardial function and tissue characteristics.Conclusion

Despite the higher volumes of ectopic PAT and ParaAT deposition in PLHIV on ART, we conclude that the magnitude of effect of inflammation in untreated PLHIV is greater than that of visceral cardiac adiposity on impairments in LV function and myocardial tissue characteristics.Acknowledgements

We grateful acknowledge:

- Prof Ntusi CMR research group for mentorship and guidance.

- The support of Cape Universities Body Imaging Centre (CUBIC)

References

- Ntusi N A B. HIV and myocarditis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12: 561-565.

- Bonou M. et al. Imaging modalities for cardiovascular phenotyping in asymptomatic people living with HIV. Vascular Medicine. 2020;26(3):326-337.

- Ntusi N, et al. HIV-1-Related Cardiovascular Disease Is Associated With Chronic Inflammation, Frequent Pericardial Effusions, and Probable Myocardial Edema. Circ Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(3): e004430.

- Buggey J. HIV and pericardial fat are associated with abnormal cardiac structure and function among Ugandans. Heart. 2020;106(2):147-153.

- Nelson MD, et al. Cardiac Steatosis and Left Ventricular Dysfunction in HIV-Infected Patients Treated With Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2014;7(11): 1175-1177.

Figures

Table 2. Continuous data are shown as mean ± SD. ANOVA post-hoc tests (p<0.05): a) HIV on ART vs HIV not on ART, b) HIV on ART vs Controls, c) HIV not on ART vs Controls. LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; SV, stroke volume; EF, ejection fraction; LVM, left ventricular mass; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter. Characteristics with an i are indexed to body surface area.