5427

Reducing contrast agents’ residuals in hospital wastewater: the GREENWATER study1Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy, 2Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy, 3IRCCS Policliico San Donato, Milano, Italy, 4IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, Milano, Italy, 5Università degli Studi di Milano - IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, Milan, Italy

Synopsis

In order to provide preliminary data about the potential reduction of contrast agents’ residuals in hospital wastewater and to estimate contrast agent excretion in the first hour after administration, the GREENWATER study aims to prospectively monitor over a 12-months timeframe the quantity of retrievable ICAs and GBCAs from urine collected from outpatients within an hour from contrast agent administration, also evaluating the influence of patient age and sex and the overall rate of acceptance to participate to the study. Our current purpose is to provide a first glance on this initial experience.

Background

Imaging techniques, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), represent fundamental diagnostic tools in almost every clinical setting, with further and ever-growing applications in interventional imaging-guided procedures. Most iodine-based contrast agents (ICAs) are derivatives of the triiodobenzoic acid and are largely eliminated via urinary excretion without metabolization, generally within 24 hours from administration. Conversely, gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) are chelated complexes of the trivalent gadolinium ion with polyaminocarboxylic acids. Chelation ensures that the toxic effects of the free gadolinium are avoided and allows for the excretion of GBCAs without metabolization. ICAs and GBCAs relatively rapid excretion profile after intravenous administration in humans could allow for a considerable recovery by specific targeting of hospital sewage, for example if outpatients being administered ICAs or GBCAs could be kept in the facility long enough to allow for the urinary excretion of a sizable quantity of these contrast agents in monitored sewers. The GREENWATER study aims to prospectively monitor over a 12-months timeframe the quantity of retrievable ICAs and GBCAs from urine collected from outpatients within an hour from contrast agent administrationMethods

Inclusion criteria for the study were outpatients (both males and females) scheduled to perform a contrast-enhanced MRI or a contrast-enhanced CT for any reason, aged ≥18 years. We excluded those unable to provide informed consent, and those who did not wish to extend the observation time after examination to 60 min after contrast administration or to provide the urine sample requested for the study, those with known infectious disease in the last two months or signs and symptoms of ongoing infectious diseasesPatients eligible for enrolment will be informed about the study aims and design. For each eligible patient, data on age, sex, and type and time of scheduled examination (categorized as early, late morning, afternoon) will be recorded to estimate the possible impact on the two endpoints by these variables, namely 1) the acceptance rate by the patients; and 2) the urinary excretion of contrast agents per patient within one hour, in relation to patients age and sex, season and other covariates/predictors.

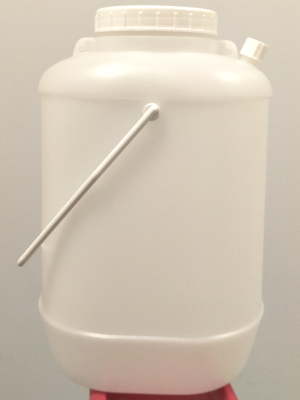

After standard anamnesis, all enrolled patients will undergo their scheduled contrast-enhanced examination (CT or MRI) without any modifications to the currently-adopted clinical protocols. Contrast agent molecule, concentration, dose, and injection rate will be recorded for each patient, alongside the examination protocol, type, and diagnostic purpose. After the examination, the usual observation time of approximately 30 min will be extended to 45−50 min, with a total timespan after contrast agent administration of 60 min. During this time interval and specifically before leaving the hospital, enrolled patients will be required to urinate in a urine containe.

Results

After the first three months of enrolment, acceptance rate was 126/130 (96%, 95% confidence interval, CI, 94−100%). Patients’ median age was 59 years (interquartile range, IQR, 47−73 years), 65 males (50%). Overall, 74 patients underwent MRI and 56 CT. In particular, 58 (45%) patients were referred to imaging for cardiac indications, 48 (36%) for neurological indications, and 24 (18%) for other reasons. The median volume of iodine injected per patient was 22.2 g (IQR 19.2−26.0 g), whereas the median volume of gadolinium injected per patient was 1.2 mol (IQR 1.0−1.6 mol). The median volume of collected urine was 100 mL (IQR 70−144 mL). ICAs recovered from urine was 53.31% [IQR 37.99%–88.33%], while GBCAs recovered from urine was 13.94% [IQR 10.24–19.76%].Conclusions

Patients’ acceptance rate was very high (over 90%), indicating a high patients’ “green” awareness and interest for a sustainable radiology. The percentage of iodine and gadolinium molecules recovered from patients’ urine is more than half for iodine and only 14% for gadolinium. Urine samples displayed sufficient volumes to allow patient-by-patients analyses for building a model to predict the amount of iodine and gadolinium retrievable using this approach.Acknowledgements

Funding for this study: Bracco imaging.References

1. Weissbrodt D, Kovalova L, Ort C, et al (2009) Mass Flows of X-ray Contrast Media and Cytostatics in Hospital Wastewater. Environ Sci Technol 43:4810–4817

2. Nowak A, Pacek G, Mrozik A (2020) Transformation and ecotoxicological effects of iodinated X-ray contrast media. Rev Environ Sci Bio/Technology 19:337–354

3. Sengar A, Vijayanandan A (2021) Comprehensive review on iodinated X-ray contrast media: Complete fate, occurrence, and formation of disinfection byproducts. Sci Total Environ 769:144846

4. Ebrahimi P, Barbieri M (2019) Gadolinium as an Emerging Microcontaminant in Water Resources: Threats and Opportunities. Geosciences 9:93

5. Brünjes R, Hofmann T (2020) Anthropogenic gadolinium in freshwater and drinking water systems. Water Res 182:115966

6. Dekker HM, Stroomberg GJ, Prokop M (2022) Tackling the increasing contamination of the water supply by iodinated contrast media. Insights Imaging 13:1–9

7. Rogowska J, Olkowska E, Ratajczyk W, Wolska L (2018) Gadolinium as a new emerging contaminant of aquatic environments. Environ Toxicol Chem 37:1523–1534

8. Papoutsakis S, Afshari Z, Malato S, Pulgarin C (2015) Elimination of the iodinated contrast agent iohexol in water, wastewater and urine matrices by application of photo-Fenton and ultrasound advanced oxidation processes. J Environ Chem Eng 3:2002–2009

9. Thomsen HS (2017) Are the increasing amounts of gadolinium in surface and tap water dangerous? Acta radiol 58:259–263

10. Kaegi R, Gogos A, Voegelin A, et al (2021) Quantification of individual Rare Earth Elements from industrial sources in sewage sludge. Water Res X 11:100092

11. Brünjes R, Bichler A, Hoehn P, Lange FT, Brauch H-J, Hofmann T (2016) Anthropogenic gadolinium as a transient tracer for investigating river bank filtration. Sci Total Environ 571:1432–1440