5382

Artifacts in breast imaging when using SPAIR fat suppression in the presence of large B0 variations1Biomedical Engineering, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 2Radiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 3Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Radiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 5Carbone Cancer Center, Madison, WI, United States, 6Holden Cancer Center, Iowa City, IA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Breast, Breast, Fat Suppression

In this educational presentation we will discuss the impact of B0 field inhomogeneity on fat suppression related artifacts when using adiabatic spectrally selective inversion preparation in the setting of breast MRI setting.Introduction

Clinical breast MRI places high technical demands on B0 and B1 homogeneity due to the challenges caused by dielectric effects of the complex anatomy. Uniform fat suppression is needed to facilitate diagnostic assessment, and this can be particularly challenging when imaging in the presence of local susceptibility sources such as biopsy clips or chemotherapy ports. Patient specific shimming can help, but clinical MRI systems typically have limited shim geometries. Even with higher order shimming, MRI systems do not have sufficient flexibility to match the array of complex geometries encountered in the clinical environment. A common method to overcome B1 inhomogeneity is the use of adiabatic radiofrequency (RF) pulses with spectral attenuated inversion recovery (SPAIR) [1,2]. Adiabatic pulses with wide spectral bandwidth can provide some robustness to B0 variations [3] but, SPAIR has limitations to the overall B0 variation that can be accommodated. This can introduce complex fat and water signal dynamics in regions of B0 inhomogeneity where water and fat can be far from the imaging resonance frequency. This exhibit demonstrates the off-resonance sensitivity and failure modes of the SPAIR fat suppression approach at 3T in the setting of breast MRI.Methods

Phantom Imaging: A breast-mimicking phantom that included separate regions of fat and water (CaliberMRI, Boulder, CO) was imaged using a T2w fast spin echo acquisition with an adiabatic SPAIR RF pulse on a 3T clinical MRI (Premier, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). B0 field maps (IDEAL-IQ, GE Healthcare) and B1 maps were also collected. Initially, the scanner prescan software determined the center frequency as is typical. To simulate B0 field inhomogeneity, scanning was repeated multiple times with the center frequency manually adjusted each time. The frequency offset was incremented in steps of 110Hz spanning the range of -550Hz to +550Hz (11 total offsets). The signals from fat, water, and the background in air were measured using ROIs in corresponding regions of the phantom. The ROIs were then measured in each image volume corresponding to each center-frequency offset.Volunteer Imaging: A normal healthy volunteer was consented and imaged under IRB approval. T2w images and B0 maps were collected as the linear x-shim (volunteer left/right direction) of the MRI system was varied. In total, images were collected at 3 separate shim settings including the system optimized shim values as well as +200 a.u. and -200 a.u. to create a linearly varying B0 across the body.

Results

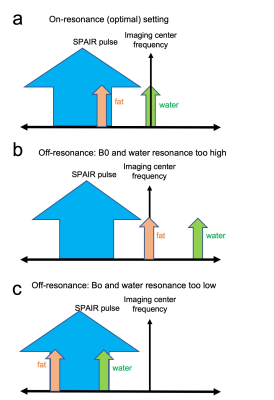

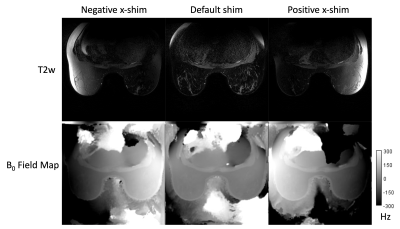

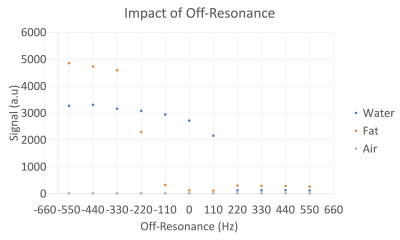

Phantom Imaging: A graph of the water and fat signals as a function of center frequency demonstrates the complex asymmetry due to off-resonance (Fig.1). High quality fat suppression is achieved when the center frequency is on- and near-resonance (-110 to 110Hz) with bright water signal and suppressed fat signal. At more negative frequency offsets consistent with lower B0, there is a loss of fat saturation and both water and fat signals become bright. The SPAIR pulse is shifted far enough below the fat resonance such that it no longer inverts fat signal. However, at positive frequency offsets consistent with higher B0, the SPAIR pulse begins to overlap with the resonance frequency of water resulting in inversion of both water and fat leading to signal loss of both chemical species. Fig. 2 shows the relation of the SPAIR pulse to fat, water, and imaging frequencies.Volunteer Imaging: Images from the normal volunteer are consistent with the phantom studies. When imaging with the system optimized settings, we can see highly uniform fat suppression across the breasts and axilla with uniform B0 (Fig 3, center column). When large negative or positive x- shims were introduced, loss of fat saturation was observed in the regions of very low B0 and loss of both fat and water signals were observed in regions of very high B0. Comparison of the images from negative vs. positive x-shim demonstrates the ability to invert these signal characteristics based on the local B0.

Discussion and Conclusion

Adiabatic SPAIR approaches provide homogeneous fat saturation that is robust to B1 variation and is relatively robust to B0 field variations. However, it is also known to be sensitive to large B0 variations due to the inherent resonance frequency separation between water and fat. Alternatively, if the spectral bandwidth of the SPAIR pulse is narrow, this can result in poor overall B0 robustness while still resulting in a loss of water signal if the SPAIR pulse overlaps with water (case not shown here). We demonstrate the effect in the setting of T2w imaging however similar fat/water signal behavior would be expected in other settings that use SPAIR such as T1w Breast DCE. Although SPAIR based approaches provide several advantages in the setting of breast imaging, clinicians should be aware of the asymmetric sensitivity and failure modes of the approach when imaging in less homogeneous B0 settings. In particular, the loss of both fat and water signals in regions of more positive B0 inhomogeneity may not be obvious and it is important to reference non-fat suppressed images.Acknowledgements

NIH NCI R01CA248192. This research is supported by the departments of Radiology and Medical Physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The University of Wisconsin-Madison receives research support from GE Healthcare.References

1. Lauenstein TC, Sharma P, Hughes T, Heberlein K, Tudorascu D, Martin DR. Evaluation of optimized inversion recovery fat-suppression techniques for T2-weighted abdominal MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 27:1448–14542.

2. Ribeiro MM, Rumor L, Oliveira M et al (2013) STIR, SPIR and SPAIR techniques in magnetic resonance of the breast: a comparative study. JBiSE 6:395–4023.

3. Tannús A, Garwood M (1997) Adiabatic pulses. NMR Biomed 10:423–434.

Figures

Figure 1. Scatter plot of asymmetry in the off-resonance B0 vs. signal measured in the T2w images for water, fat, and air measured in the phantom. When imaging within +/-110 Hz, water signals remain bright with fat signals being suppressed. At more negative off-resonance fat suppression is lost. Conversely, at larger positive off-resonance, fat remains suppressed, but the water signal also becomes suppressed.