5378

Imaging Cerebral Inflammation: Translational Findings from Preclinical MRI & 31P MRS1University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, Preclinical

Stroke is routinely diagnosed using clinical MRI and MRS, which provide information on tissue pathophysiology and metabolism respectively. However, within such a complex lesion, it is difficult to establish the relative contributions of the ischaemic and inflammatory components on the resulting pathophysiology. It would be useful for clinicians to be able to identify tissue MR signals attributable to cerebral inflammation and discern them from MR signals pertaining to ischaemic injury, facilitating targeted therapeutic strategies.

Clinical Significance

Every 40 seconds, someone in the US suffers a stroke18 – the single greatest cause of severe disability. Ischaemic stroke is the most common type of stroke and occurs when an artery is blocked by a blood clot, interrupting the brain’s blood supply18. In brief, insufficient blood flow starves the brain of oxygen and nutrients, resulting in neuronal cell death. However, strokes are more complex than this picture might suggest. Low blood flow around the core of the lesion gives rise to distinct pathology and strokes are invariably accompanied by an inflammatory response. Stroke is routinely diagnosed using clinical MRI and MRS, which provide information on tissue pathophysiology and metabolism respectively. However, within such a complex lesion, it is difficult to decipher the relative contributions of the ischaemic and inflammatory components to the resulting pathophysiology. It would be useful for clinicians to be able to discern the MR signals attributable to cerebral inflammation from those pertaining to ischaemic injury, facilitating targeted therapeutic strategies.Preclinical MRI & MRS Findings

We can separate the contribution of the ischaemic and inflammatory components of the stroke pathology using preclinical models that compare and combine lesions generated by the archetypal pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) - a key propagator of cerebral inflammation in stroke1 with those produced by the potent vasoconstrictive agent, endothelin-1 (ET-1)20. Microinjection of IL-1β into the rodent brain drives leukocyte recruitment, activates resident tissue macrophages and drives local cytokine and chemokine production21. ET-1 microinjection into the rodent brain generates a focal ischaemic stroke-like lesion, characterised by neuronal cell death and the absence of a typical inflammatory response that is devoid of leukocyte recruitment or blood-brain-barrier breakdown22,23,24,25,26. This is in contrast to the classic middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model of ischaemic stroke, which generates extensive and complex lesions involving an acute inflammatory response27,28,29.A body of preclinical MR work has attempted to characterise the IL-1β-induced inflammatory response and ET-1-induced ischaemic lesion in the rodent brain in terms of MRI- and phosphorus (31P) MRS-visible signals and discern them.

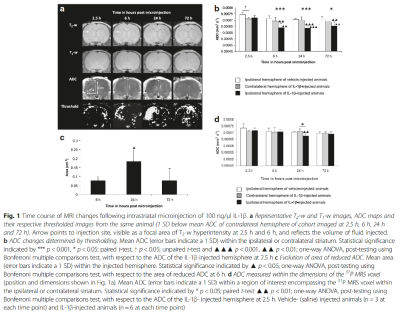

Intrastriatal microinjection of IL-1β in vivo induces a chronic reduction in the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of tissue water on MRI2. In acute cerebral ischaemia, reduced ADC is associated with compromised cerebral blood flow and correlates with the loss of high-energy phosphorus metabolites detected using 31P MRS3,4,5,6,7,8. Reduced oxygen and glucose delivery by the circulation leads to a decline in intracellular ATP, precipitating the failure of ATP-dependent ion pumps such as the Na+/K+-ATPase that regulate cell volume9. The increase in intracellular Na+ concentration promotes the osmotically driven movement of water from the extracellular to intracellular compartment10 causing cell swelling, reducing the extracellular space, and ADC11,12,13. Interestingly, despite inducing a persistently depressed ADC, classically associated with energy failure in the MCAO stroke model, IL-1β induces intraparenchymal vessel dilation14 and increases regional cerebral blood volume on MRI with no evidence of an increase in 1H MRS-detectable lactate2, which is inconsistent with an ischaemic event.

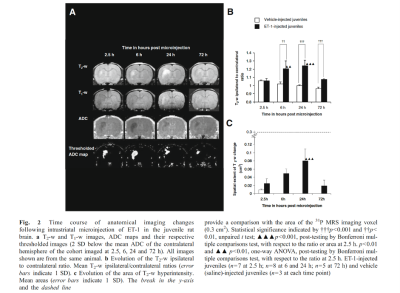

We presented the first study to address the energetic status of brain parenchyma when ADC becomes reduced by measuring 31P MRS-detectable metabolites following IL-1β challenge in an ex vivo preparation of organotypic hippocampal-slice cultures (OHSCs)15, which preserve synaptic connectivity and cellular organisation but avoid vasculature-related confounding factors such as perfusion changes, BBB breakdown and leukocyte recruitment16. Energy status, as defined by the PCr to γATP ratio, was unperturbed suggesting that IL-1β does not alter the energy status of brain parenchyma per se15. This gave rise to the question of whether intrastriatal microinjection of IL-1β may alter the energy metabolism of brain parenchyma in vivo where its effects may be augmented by vasculature-related neutrophil recruitment, BBB breakdown and perfusion changes. We further showed that 31P MRS-detectable energy status remained unaltered in vivo despite a chronically reduced ADC17. Previous work investigating BBB breakdown2 and microglial activation14 have not accounted for the IL-1β-induced chronic reduction in ADC either.

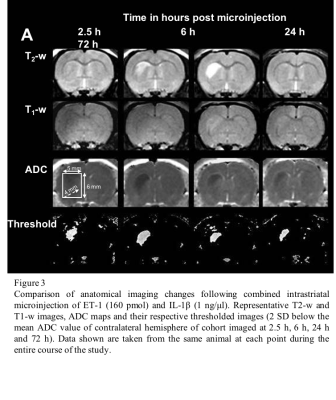

Finally, we have characterised a combined IL-1β and ET-1 challenge in vivo, mimicking a focal stroke-like lesion using MR, which compared to the ET-1-induced lesion, demonstrates attenuated end-point oedema and greater leukocyte recruitment without exacerbating the area of cell death (unpublished data). Few differences were observed on anatomical imaging with the ET-1-induced lesion exhibiting greater T2-w hyperintensity and area at 72 h, and a greater area of T1-w hypointensity at 2.5 h (Figure 3).

Conclusions

What can we learn by comparing the characterisation of the pro-inflammatory IL-1β-induced lesion with a the ischaemic ET-1-induced lesion in vivo in real-time? Clearly, cerebral inflammation and ischaemia exhibit distinct MRI signals (Figures 1 and 2). The effects of IL-1β are not detectable using T1-w or T2-w MRI whereas those of ET-1 are prominent, extensive and chronic. With respect to ADC changes, the temporal and spatial evolutions are distinct. Interestingly, despite both lesions demonstrating a chronically reduced ADC, typically associated with MCAO-induced energy failure, a 31P MRS-detectable reduction in the PCr to γATP ratio was not observed in either model, suggesting dissociation of tissue water diffusion and metabolic changes in pure ischaemic and pure inflammatory brain lesions. The cause of the reduction in ADC remains to be deciphered but BBB breakdown, microglial activation and metabolic failure are unlikely.Acknowledgements

References

1Walsh JG, Muruve DA, Power C. Inflammasomes in the CNS. Nat Rev

Neurosci. 2014;15(2):84–97.

2A.M. Blamire, D.C. Anthony, B. Rajagopalan, N.R. Sibson, V.H. Perry, P. Styles,

Interleukin-1beta-induced changes in blood–brain barrier permeability, apparent

diffusion coefficient, and cerebral blood volume in the rat brain: a magnetic

resonance study, J. Neurosci. 20 (2000) 8153–8159.

3T. Back, M. Hoehn-Berlage, K. Kohno, K.A. Hossmann, Diffusion nuclear magnetic

resonance imaging in experimental stroke. Correlation with cerebral

metabolites, Stroke 25 (1994) 494–500.

4A.L. Busza, K.L. Allen, M.D. King, N. van Bruggen, S.R. Williams, D.G. Gadian,

Diffusion-weighted imaging studies of cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Potential

relevance to energy failure, Stroke 23 (1992) 1602–1612.

5H.A. Crockard, D.G. Gadian, R.S. Frackowiak, E. Proctor, K. Allen, S.R. Williams,

R.W. Russell, Acute cerebral ischaemia: concurrent changes in cerebral blood

flow, energy metabolites, pH, and lactate measured with hydrogen clearance

and 31P and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. II. Changes during

ischaemia, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 7 (1987) 394–402.

6M.E. Moseley, Y. Cohen, J. Mintorovitch, L. Chileuitt, H. Shimizu, J. Kucharczyk,

M.F. Wendland, P.R. Weinstein, Early detection of regional cerebral ischemia in

cats: comparison of diffusion- and T2-weighted MRI and spectroscopy, Magn.

Reson. Med. 14 (1990) 330–346.

7H. Naritomi, M. Sasaki, M. Kanashiro, M. Kitani, T. Sawada, Flow thresholds for

cerebral energy disturbance and Na+ pump failure as studied by in vivo 31P and

23Na nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 8

(1988) 16–23.

8A. van der Toorn, E. Sykova, R.M. Dijkhuizen, I. Vorisek, L. Vargova, E. Skobisova,

M. van Lookeren Campagne, T. Reese, K. Nicolay, Dynamic changes

in water ADC, energy metabolism, extracellular space volume, and tortuosity

in neonatal rat brain during global ischemia, Magn. Reson. Med. 36 (1996)

52–60.

9J. Astrup, Energy-requiring cell functions in the ischemic brain. Their critical

supply and possible inhibition in protective therapy, J. Neurosurg. 56 (1982)

482–497.

10B.A. Bell, L. Symon, N.M. Branston, CBF and time thresholds for the formation

of ischemic cerebral edema, and effect of reperfusion in baboons, J. Neurosurg.

62 (1985) 31–41.

11A.J. Hansen, C.E. Olsen, Brain extracellular space during spreading depression

and ischemia, Acta Physiol. Scand. 108 (1980) 355–365.

12K. Kohno, M. Hoehn-Berlage, G. Mies, T. Back, K.A. Hossmann, Relationship

between diffusion-weighted MR images, cerebral blood flow, and energy state

in experimental brain infarction, Magn. Reson. Imaging 13 (1995) 73–80.

13H.B. Verheul, R. Balazs, J.W. Berkelbach van der Sprenkel, C.A. Tulleken, K.

Nicolay, K.S. Tamminga, M. van Lookeren Campagne, Comparison of diffusion weighted MRI with changes in cell volume in a rat model of brain injury, NMR

Biomed. 7 (1994) 96–100.

14D.C. Anthony, S.J. Bolton, S. Fearn, V.H. Perry, Age-related effects of interleukin-

1 beta on polymorphonuclear neutrophil-dependent increases in blood–brain

barrier permeability in rats, Brain 120 (Pt 3) (1997) 435–444.

15Saggu R, Morrison B 3rd, Lowe JP and Pringle AK. Interleukin-1beta does not affect the energy metabolism of rat organotypic hippocampal-slice cultures. Neurosci Lett. 2012 Feb 6; 508(2): 114-8.

16L. Stoppini, P.A. Buchs, D. Muller, A simple method for organotypic cultures of

nervous tissue, J. Neurosci. Methods 37 (1991) 173–182.

17Saggu R. Interleukin-1beta-induced reduction of tissue water diffusion in the juvenile rat brain on ADC MRI is not associated with 31P MRS-detectable energy failure. J Inflamm (Lond). 2016 Mar 17; 13:9.

18Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153–e639.

19Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer's disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 Census. Neurology.

20Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascularendothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–5.

21D. Anthony, R. Dempster, S. Fearn, J. Clements, G. Wells, V.H. Perry, K. Walker, CXC chemokines generate age-related increases in neutrophil-mediated brain inflammation and blood–brain barrier breakdown, Curr. Biol. 8 (1998) 923–926

22Agnati LF, Zoli M, Kurosawa M, Benfenati F, Biagini G, et al. A new model of focal brain ischemia based on the intracerebral injection of endothelin-1. Ital J Neurol Sci.1991;12:49–53.

23Frost SB, Barbay S, Mumert ML, Stowe AM, Nudo RJ. An animal model of capsular infarct: endothelin-1 injections in the rat. BehavBrain Res. 2006;169:206–11.

24Fuxe K, Kurosawa N, Cintra A, Hallstrom A, Goiny M, et al. Involvement of local ischemia in endothelin-1 induced lesions of the neostriatum of the anaesthetized rat. Exp Brain Res.1992;88:131–9.

25Hughes PM, Anthony DC, Ruddin M, Botham MS, Rankine EL, et al. Focal lesions in the rat central nervous system induced by endothelin-1. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1276–86.

26Moyanova SG, Kortenska LV, Mitreva RG, Pashova VD, Ngomba RT, Nicoletti F. Multimodal assessment of neuroprotection applied to the use of MK-801 in the endothelin-1 model of transient focal brain ischemia. Brain Res. 2007;1153:58–67.

27Lo EH, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:399–415.

28Mergenthaler P, Dirnagl U, Meisel A. Pathophysiology of stroke: lessons from animal models. Metab Brain Dis. 2004;19:151–67.

29Mitsios N, Gaffney J, Kumar P, Krupinski J, Kumar S, Slevin M. Pathophysiology of acute ischaemic stroke: an analysis of common signalling mechanisms and identification of new molecular targets. Pathobiology. 2006;73:159–75.

Figures

Fig. 1 Time course of MRI changes following intrastriatal microinjection of 100 ng/μl IL-1β.

Comparison of anatomical imaging changes following combined intrastriatal microinjection of ET-1 (160 pmol) and IL-1β (1 ng/μl). Representative T2-w and T1-w images, ADC maps and their respective thresholded images (2 SD below the mean ADC value of contralateral hemisphere of cohort imaged at 2.5 h, 6 h, 24 h and 72 h). Data shown are taken from the same animal at each point during the entire course of the study.