5331

A highly automated experimental setup to perform PHIP via proton exchange with high pressure and high reproducibility at various magnetic fields1Section Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology and Neuroradiology, University Medical Center Schleswig - Holstein, Kiel University, Kiel, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas), Contrast Agent

The PHIP-X methodology is a novel approach to produce contrast agents for metabolic MRI by hyperpolarization and combines the high polarization resulting from pH2 addition with the versatility of proton exchange. However, the polarization yield and reproducibility have to be improved. The proposed setup provides reproducible and well controlled experimental conditions for PHIP-X, including a pH2 pressure of up to 100 bar and a magnetic field of up to 95 mT. Using this setup allowed to reach high 1H polarizations of the transfer agent and to transfer the polarization to 13C in the target molecule glucose successfully.Introduction

MRI with hyperpolarized contrast agents has allowed imaging of metabolism in real-time and with unprecedented sensitivity using different hyperpolarization methods. One hyperpolarization method uses parahydrogen (pH2) as a source of spin order to polarize a target molecule. These methods are cost efficient and usually fast. However, a limitation is the need of an unsaturated precursor for hydrogenation (PHIP1 and PHIP-SAH2) or molecule that undergoes reversible exchange with pH2 at a catalyst (SABRE3). Recently, it was proposed to transfer the pH2-derived polarization to other molecules via proton exchange (SABRE-RELAY4, PHIP-X5). PHIP-X combines high polarization resulting from pH2 addition with the versatility of proton exchange. Here, a transfer agent is polarized by addition of pH2 before the polarization is transferred via proton exchange to a target molecule. However, for several applications, the polarization yield and reproducibility must be improved. Here, we propose a setup that provides reproducible and well controlled experimental conditions for PHIP-X, including a pH2 pressure of up to 100 bar and a magnetic field of up to 95 mT.Methods

Chemistry:100 µl of 830 mM 13C6-D-Glucose (Sigma Aldrich, CAS: 110187-42-3) in Dimethylsulfoxid-d6 (DMSO-d6, Sigma Aldrich, CAS: 2206-27-1), and 8 µl of Propargyl alcohol (99%, Sigma Aldrich, CAS: 107-19-7) were mixed with 900 µl of 7 mM catalyst ([Rh(dppb)(COD)]BF4, 98%, Sigma Aldrich, CAS: 79255-71-3) in acetone-d6 (Sigma Aldrich, CAS: 666-52-4).

Polarizer:

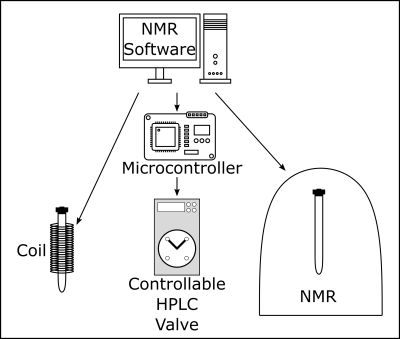

The polarizer consisted of a copper tube with a resistive coil, programmable power supply, multifunctional HPLC valve (Knauer Azura 4.1) and 1T benchtop NMR. The valve guided the pH2 into the copper tube (26 cm length, diameter 6 mm), holding the liquid sample, and transferred it into the NMR (Spinsolve 43 Carbon, Magritek, Fig. 1). The valve was controlled using a custom-made microprocessor circuit board. The coil (1 mm copper wire, 5200 windings, NGL 202 power supply, Rohde & Schwarz) around the tube generated a magnetic field during the hydrogenation of up to Bhydro = 95 mT. Other components included a pressure control valve, flow regulator and two exhausts. All parts were rated for pressures exceeding 100 bar. About 95% enriched pH2 was produced using a high-pressure pH2 generator at 25 K (unpublished).

Experiment:

After injecting the sample and closing the reactor, the experiment was started in the NMR software, which set the magnetic field and triggered the board controlling the valve (Fig. 2). The valve connected the pH2 supply (35 bar) with the reactor, initiating the hydrogenation. After five seconds, the valve connected the reactor to the tube inside the NMR, where the data acquisition was started 1.5 seconds later (either pulse-acquisition 1H spectra or spin order transfer from 1H to 13C using the DEPT sequence (135° pulse, 140 Hz)). Note that the sample passed through earth magnetic field during the transfer from Bhydro to the detection field of 1 T.

Results

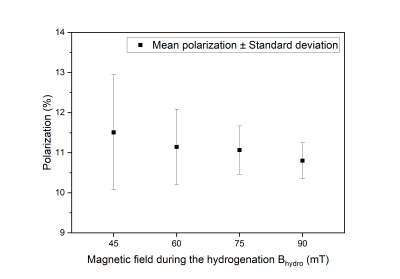

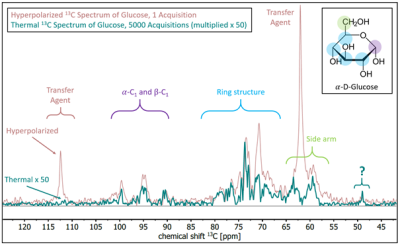

First, we investigated the hyperpolarization on the transfer agent. We conducted the experiment at four different magnetic fields between 45 mT and 90 mT (five times each). A mean polarization of about 11% was observed (Fig. 3), with the highest polarization and the largest variation at 45 mT. The polarization (P) and the standard deviation (SD) decreased with increasing fields from P(1H) ≈ 11.5% to 11% and from SD = 1.4% (45 mT) to 0.4% (90 mT), respectively.Next, we investigated the polarization transfer from the transfer agent to the biological target molecule 13C6-D-glucose. PHIP-X was conducted using a solution containing glucose, propargyl alcohol and the catalyst at 35 bar pH2 and Bhydro = 60 mT. Strong 13C signal enhancement was observed after 1H-to-13C polarization transfer with DEPT (135°, 140 Hz). An enhancement of approx. 80-fold was found with respect to thermal equilibrium using the same sequence, corresponding to a polarization of 0.0071% (Fig. 4, across all 13C resonances of glucose).

Discussion

The presented setup allowed highly automated and reproducible PHIP-X experiments with pH2 pressures of 35 bar and external magnetic fields of up to 90 mT. High 1H polarization of the transfer agent of ≈11% was reached. SD was higher at lower fields, which may be connected to changing relaxations and more chaotic spin dynamics at lower fields.The polarization transfer to 13C in the target glucose was successful, although on a lower level of P(13C) ≈ 0.0071%. This polarization appears low with respect to other methods and for biomedical imaging, it should be noted that the concentration was high (83 mM) and further optimizations are ongoing. Specifically, the optimization of the chemical exchange rates between transfer agent and target molecule appears to be very promising. The advantage of polarization transfer via proton exchange remains that it is universally applicable to all exchanging molecules

The removal of catalyst and transfer agent after polarization is still a challenge for biomedical applications and remains a future research scope.

Conclusion

The presented setup allowed us to conduct highly automated PHIP-X experiments and improving the reproducibility significantly. A wide range of magnetic fields (up to 95 mT) and a high pH2 pressures (up to 100 bar) assures fast hydrogenation and facilitates parameter optimization. As a successful proof-of-concept, the setup is the starting point for further optimizing this interesting variant of PHIP.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the Emmy Noether Program “Metabolic and Molecular MR” (HO 4604/2-2), the research training circle “Materials for Brain” (GRK 2154/1-2019), DFG-RFBR grant (HO 4604/3-1, No 19-53-12013), Cluster of Excellence “Precision Medicine in Inflammation” (PMI 2167), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the framework of the e:Med research and funding concept (01ZX1915C). Kiel University and the Medical Faculty are acknowledged for supporting the Molecular Imaging North Competence Center (MOIN CC, MOIN 4604/3). MOIN CC was founded by a grant from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Zukunftsprogramm Wirtschaft of Schleswig-Holstein (Project no. 122-09-053). The Russian team thanks the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Grant 19-53-12013) for financial support.References

1. Hövener, J.-B.; Pravdivtsev, A. N.; Kidd, B.; Bowers, C. R.; Glöggler, S.; Kovtunov, K. V.; Plaumann, M.; Katz-Brull, R.; Buckenmaier, K.; Jerschow, A.; Reineri, F.; Theis, T.; Shchepin, R. V.; Wagner, S.; Bhattacharya, P.; Zacharias, N. M.; Chekmenev, E. Y. Parahydrogen-Based Hyperpolarization for Biomedicine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (35), 11140–11162. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201711842.

2. Reineri, F.; Cavallari, E.; Carrera, C.; Aime, S. Hydrogenative-PHIP Polarized Metabolites for Biological Studies. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2021, 34 (1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-020-00904-x.

3. Adams, R. W.; Aguilar, J. A.; Atkinson, K. D.; Cowley, M. J.; Elliott, P. I. P.; Duckett, S. B.; Green, G. G. R.; Khazal, I. G.; López-Serrano, J.; Williamson, D. C. Reversible Interactions with Para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science 2009, 323 (5922), 1708–1711. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1168877.

4. Iali, W.; Rayner, P. J.; Duckett, S. B. Using Parahydrogen to Hyperpolarize Amines, Amides, Carboxylic Acids, Alcohols, Phosphates, and Carbonates. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4 (1), eaao6250. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao6250.

5. Them, K.; Ellermann, F.; Pravdivtsev, A. N.; Salnikov, O. G.; Skovpin, I. V.; Koptyug, I. V.; Herges, R.; Hövener, J.-B. Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization Relayed via Proton Exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (34), 13694–13700. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c05254.

Figures