5321

Imaging sexual dimorphism in white matter across the lifespan: A rat model of healthy ageing1Molecular Neurobiology and Neuropathology, Instituto de Neurociencias de Alicante, San Joan d'Alacant, Spain, 2Cellular and Systems Neurobiology, Instituto de Neurociencias de Alicante, San Joan d'Alacant, Spain

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Aging

White matter microstructure evolves across the lifespan due to maturation and degeneration. Recently, MR imaging in humans uncovered region- and sex-specific trajectories of microstructural integrity decline, suggesting prolonged neoteny in the female brain. Here, using advanced diffusion-weighted MRI, we characterize the contribution of different cell-specific white matter biomarkers in a longitudinal rat model of healthy ageing, from puberty to early senescence. Our results validate the use of a rat model of healthy ageing for dissecting longitudinal brain ageing patterns, replicate the sexual dimorphism found in humans and points at myelin as the neurobiological substrate driving the observed sex difference.

INTRODUCTION

Brain evolution through the lifespanWhite matter (WM) tissue, mainly composed of axons, glial cells and myelin, undergoes macroscopic and microscopic alterations due to maturation and degeneration of its cellular components across the lifespan1. An important aspect of WM evolution is axons myelination, key for neuronal communication and plasticity. In humans, myelination begins at gestation, and continues2 until early senescence, when a slow and gradual decline kicks in3. Similarly, axons undergo morphological changes, increasing their calibre5. While gender differences in brain microstructure have been consistently reported, differential patterns of ageing across sexes have only recently been proposed6.

MRI to study brain evolution with age

Imaging the brain non-invasively through MRI is particularly important to study ageing, as most of the research questions need in-vivo and/or longitudinal studies. MRI-derived brain size follows an asymmetrical inverted-U pattern as a function of age7. Fractional anisotropy (FA), an index sensitive to microstructural integrity but unspecific to its cellular substrate, also follows the same trend8. Previous work from our laboratory characterized the age at which such curve reaches its peak and inverts the maturation trend, interpreted as the timepoint which marks the onset of microstructural decline9. Importantly, using advanced diffusion-weighted (dw)-MRI, we unveiled that age-driven decay starts a few years later in females, in accordance with evolutionary theories and numerous recent evidences across non-MRI domains10,11.

Preclinical models of ageing

While rodents are an ideal target to study ageing, due to their relatively short life expectancy (~2-3 years) and their genetic proximity to humans, only a few imaging studies are available, and none using advanced dw-MRI and/or including both sexes. These studies generally confirm MRI sensitivity to detect age-related changes12, but do not specify the neurobiological substrate of the observed changes. Therefore, our aim was to build and characterize a rat model of healthy ageing. Specifically, we seek to i) replicate the sexual dimorphism observed in humans, and ii) use advanced MRI to dissect the neurobiological substrate driving this difference.

THEORY, ACQUISITION AND MODEL FITTING

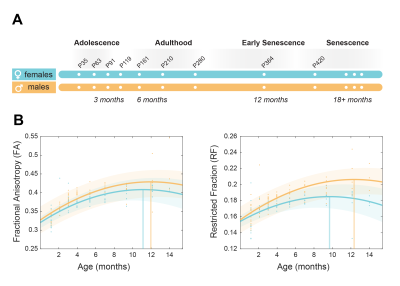

Data AcquisitionMRI longitudinal experiments on 29 Wistar rats, in the range 35-420 postnatal days (14 females) were performed on a 7T scanner (Bruker, BioSpect 70/30; Fig. 1 A for experimental design). Dw-MRI data were acquired using a stimulated echo sequence with 30 uniform distributed gradient directions, b=1000 and 2500 s/mm2, diffusion times 15, 25, 40 and 60 ms, three b=0 images, TR=3000 ms and TE=34 ms. Sixteen slices covered the whole brain with field of view 25×25 mm2, matrix size 110 × 110, in-plane resolution 0.225×0.225 mm2 and slice thickness 1 mm. A T2-weighted sequence was acquired with the same geometry, TR=3000 ms, TE=11.25 ms, 4 averages.

MRI analysis and models

Dw-MRI data was non-linearly registered to T2w scan and corrected for motion and eddy current. Data with b=1000s /mm2 was used for DTI analysis13,14 and FA maps were computed for each subject. Then, all shells were employed to fit the AxCaliber model to extract the restricted fraction (FR) and the average axonal diameter (Ax) maps, as described here9. Data were normalized and parceled using an in-house FA template and mean values in each WM region of interest (ROI) were extracted for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

According to previous work9, we tested a mixed regression model with predictors: age, sex, age squared and the interaction between age and sex. We adjusted the model separately for each dependent variable FA, FR and Ax. Random effects of ROI and time were considered in the model as repeated measures. Guided by the Akaike Information Criterion15, we chose the best model taking into account both parsimony and minimization of fit residuals. In regions in which a second order model was supported by the data, we calculated the peak of the curve and interpreted it as the age at which microstructural maturation is completed.

RESULTS

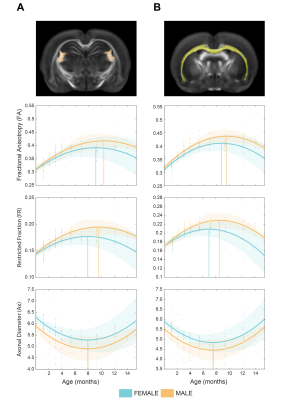

Our longitudinal data support significant main effects for age (p <0.001; for FA, FR and Ax), sex (p <0.001; for Ax), age squared (p <0.001) and sex*age interaction (p<0.01 for FA; p<0.001 for FR; p<0.05 for Ax). Microstructural maturation was reached earlier in females for FA and FR (Fig. 1 B). The presence of significant sex*age interaction replicates the trend observed in humans and demonstrate that the sexual dimorphism in brain trajectories is conserved in rats.ROI-wise analysis revealed a significant sex*age interaction in FR (p<0.001) while this effect is not significant for Ax (Fig. 2 A,B). This result points at the density/myelination of WM tracts, rather than the caliber of axons, as the neurobiological substrate driving sex differences in brain maturation and degeneration.

CONCLUSIONS

These results validate the use of a rat model of healthy ageing for dissecting the brain ageing patterns seen in humans. By using advanced diffusion MRI, we characterised biomarkers of microstructural brain development and deterioration in a longitudinal and non-invasive manner. Taken together, our results indicate that the sexual dimorphism in brain trajectories is an intrinsic microstructural property conserved across species, and that axonal density and myelination, but not caliber, is an important substrate driving this difference.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Rice, D. & Barone, S. Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environmental Health Perspectives 108, 511–533 (2000).

2. Miller, D. J. et al. Prolonged myelination in human neocortical evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 16480–16485 (2012).

3. Yeung, M. S. Y. et al. Dynamics of Oligodendrocyte Generation and Myelination in the Human Brain. Cell 159, 766–774 (2014).

4. Peters, A. The effects of normal aging on myelinated nerve fibers in monkey central nervous system. Front. Neuroanat. 3, (2009).

5. Stahon, K. E. et al. Age-Related Changes in Axonal and Mitochondrial Ultrastructure and Function in White Matter. Journal of Neuroscience 36, 9990–10001 (2016).

6. Wang Y, Xu Q, Luo J, Hu M and Zuo C (2019) Effects of Age and Sex on Subcortical Volumes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11:259. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00259

7. Courchesne, E. et al. Normal Brain Development and Aging: Quantitative Analysis at in Vivo MR Imaging in Healthy Volunteers. Radiology 216, 672–682 (2000).

8. Lebel, C. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. NeuroImage 60, 340–352 (2012).

9. Toschi, N., Gisbert, R. A., Passamonti, L., Canals, S. & De Santis, S. Multishell diffusion imaging reveals sex-specific trajectories of early white matter degeneration in normal aging. Neurobiology of Aging 86, 191–200 (2020).

10. Gilbert, T. M. et al. Neuroepigenetic signatures of age and sex in the living human brain. Nat Commun 10, 2945 (2019).

11. Goyal, M. S. et al. Persistent metabolic youth in the aging female brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116, 3251–3255 (2019).

12. Han, X., Geng, Z., Zhu, Q., Song, Z. & Lv, H. Diffusion kurtosis imaging: An efficient tool for evaluating age‐related changes in rat brains. Brain Behav 11, (2021).

13. Leemans A, Jeurissen B, Sijbers J, Jones DK. ExploreDTI: a graphical toolbox for processing, analyzing, and visualizing diffusion MR data, 2009 In 17th annual meeting of International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Berkeley, CA, USA. http://www.exploredti.com/

14. Chang LC, Jones DK, Pierpaoli C. RESTORE: robust estimation of tensors by outlier rejection. Magn Reson Med 53, 1088-95 (2005).

15. Sakamoto, Y., Ishiguro, M., and Kitagawa G. (1986). Akaike Information Criterion Statistics. D. Reidel Publishing Company.

16. Chambers, J. M. and Hastie, T. J. (1992) Statistical Models in S, Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole.

Figures

Figure 1. Brain maturation in a rat model of healthy ageing. a) Experimental scheme. N=15 male and 14 female rats underwent MRI 9 times from 1 to 14 months of age. b) White matter biomarkers (Fractional anisotropy and axonal density) showed as marginal mean over all ROIs. Both biomarkers show different maturation trends across the lifespan for males and females.

Figure 2. Cell-specific ageing trajectories measured in ROIs. a) Cell-specific white matter biomarkers (Fractional anisotropy, axonal density and diameter) were measured in the fimbria tract. b) same as a, measured in the corpus callosum. Fractional anisotropy and axonal density, but not axonal diameter, show different maturation trends across males and females.