5316

Altered cerebellar lobular volumes correlate with neurodevelopment and cognitive scores in children with ASD and ASD-siblings at an early age

Manoj Kumar1, Chandrakanta Hiremath2, Eshita Bansal2, Sunil Kumar Khokhar2, Kommu Johnvijay Sagar3, Swetha Narayanan4, Akhila S. Girimaji5, BK Yamini5, Rose Dawn Bharath2, Jitender Saini2, and M. Thamos Kishore4

1Neuroimaging and Interventional Radiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India, 2Neuroimaging and Interventional Radiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India, 3Child and Adolescents Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India, 4Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India, 5Speech pathology and Audiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India

1Neuroimaging and Interventional Radiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India, 2Neuroimaging and Interventional Radiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India, 3Child and Adolescents Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India, 4Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India, 5Speech pathology and Audiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India

Synopsis

Keywords: Neonatal, Neonatal, Neurodevelopmental disorders, ASD

Neuroimaging methods comparing individuals with ASD and healthy-controls posited a distinction in various cerebellar regions; including arrested growth of posterior vermis and reduced gray matter in right Crus I, and lobule VIII and IX. Younger cohorts of ASD, ASD-siblings, and healthy-children demonstrates volumetric differences in cerebellar lobules and look for correlation with neurodevelopmental measures. Multiple cerebellar lobules demonstrate abnormal volumes in ASD compared to ASD-sibling and healthy controls, including Vermis, dentate, and lobule I-V. Lobular volumes were also significantly correlates with social quotient, language, and cognition measures in ASD.Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairment in social and communication with narrow interests and repetitive behaviors at an early age1. Recently, there has been an increasing interest in the role of the cerebellum in pathophysiology of ASD2. Current literature suggests that the cerebellum is one of the most consistent sites of abnormality in ASD, and disruption in the cerebellum in the initial years of life is positively correlated with clinical features of ASD3-5. Neuroimaging studies on differentiating individuals with ASD and healthy controls posit a distinction in various cerebellar regions6,7. Using structural imaging, multiple studies have described the arrested growth of the posterior Vermis and consistent findings of reduced gray matter in right Crus I, lobule VIII, and lobule IX in ASD groups compared to typically developing children2,5,8. Early detection and characterization of abnormal development are vital for developing targeted therapies for early intervention that can facilitate the defining deficits of ASD and improve long-term clinical outcomes.Material and Methods

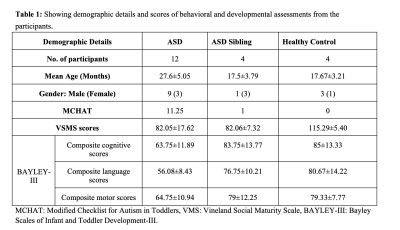

This prospective cross-sectional study was performed on Twenty children ages between 15-36months, with following cohorts: ASD (N=12; mean-age=27.67±5.1months); ASD-siblings (n=4; mean-age=17.5±3.79months); and healthy-control (N=4; mean-age=17.67±3.21months) (Table-1). All participants underwent a detailed clinical and neurodevelopmental evaluation and MRI scanning on a 3.0T Skyra MRI under natural sleep without any sedative medication. High-resolution axial 3D-T1-Weighted images with following acquisition parameters FOV=220x220mm, TR/TE/TI= 8.5/3/1610ms, FA=13o, resolution=1×1mm3 were acquired.Data processing and analysis:

MRI data were transferred to an offline workstation for further processing and quantitative analysis. As a routine preprocessing pipeline, DICOM images were converted to NifTI file format. Cerebellum was preprocessed individually using Spatially Unbiased Infratentorial Template (SUIT) toolbox9 implemented in SPM-8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Preprocessing of the data involved conducting AC-PC correction, cerebellar cropping, and isolation from T1 images. Manual cerebellar mask correction and normalization of isolated cerebellum into SUIT template space and inverse transformation by using the probabilistic cerebellar atlas (total 34 lobules; 17 lobules from each hemisphere) into individual subject space using deformation parameters from normalization (Fig. 1). The modulated gray matter probability maps were smoothed using an 8-mm FWHM Gaussian kernel9. Finally, individual cerebellar lobular and whole cerebellar volumes were extracted using ITK-SNAP tools10 (Fig. 1).Statistical methods

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD, and categoric variables, as frequencies and percentages. Demographic and neuropsychological data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Two-way ANOVA was conducted to analyze differences in the volume of cerebellum lobules across the three groups. Correlation between 34 cerebellar lobular volumes with various developmental measures such as SQ from VSMS, cognition, language, and motor scores from BSID-III was calculated using Pearson correlation. Age and gender were used as covariable to regress their confounding effects. Results were considered significant at P-values < 0.05 after FWE cluster-level correction (clusters formed with P < 0.005 at uncorrected level). SPSS-22 was used for statistical computations.Results

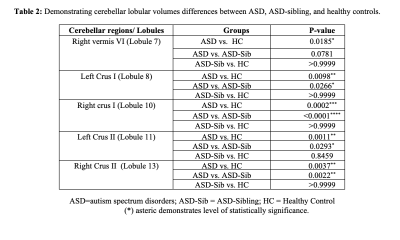

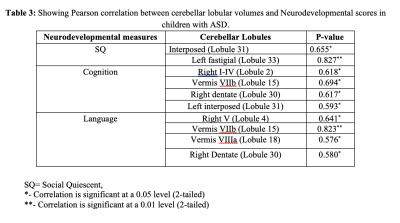

In this study, we observed significantly altered cerebellar volume at lobular levels from the specific lobules among the three groups, i.e., ASD, ASD siblings, and healthy controls at an early age (Table 1). Specifically, we observed significant differences in lobular volumes between ASD and healthy controls, including right Vermis VI, left and right Crus I and Crus II), respectively (Table-2). Similar patterns were also observed when compared between ASD and ASD siblings. Interestingly, none of the lobular regions reached to statistical level when compared between ASD-sibling and healthy controls. We also observed a significant correlation between the various developmental and behavioral scores (i.e., SQ, motor, cognitive, and language) with specific cerebellar lobular volumes (i.e., Vermis, right dentate, and left and right left lobule I-IV) associated with distinct socio-behavioral functions in children with ASD (Table-3). However, we did not find any statistically significant difference in total cerebellar volume and its correlation with between these three groups.Discussion

Neuroanatomical diversity appears to account for a substantial proportion of risk for ASD11,12. Specifically, disrupted growth of cerebellum in initial years of life is positively correlated with clinical features of ASD3-5. The vermis is one of the most implicated cerebellum structures in children with ASD13-15. Our study has also found an increase in gray matter volume in Vermis and dentate in ASD children compared to healthy controls, and the altered lobular volumes were also positively correlated with behavioral and developmental measures like social quotient and cognitive, motor, and language scores. Our findings demonstrate that these altered lobular volumetric differences may be due to abnormal neuronal pruning at an early age in children with ASD16,17. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that investigated cerebellar volumetric differences at such an early age with three different groups, i.e., children with ASD, ASD-siblings, and healthy controls.Conclusion

New findings demonstrate that early brain imaging holds great promise for early targeted interventional therapies in children with ASD. Early altered cerebellum volumes in ASD can be captured using structural MRI during early childhood and may inform much-needed advancements in the early detection of ASD. Alterations in volumes of specific lobules of the cerebellum have been found in preschool ASD children, which can be used as potential imaging biomarkers for early evaluation and characterization of ASD at a younger age.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the children and family members who gave their time and energy to participate. We also thank the funding agency (DBT, Govt. India, Grant Award Number: DBT-RF/007/303/2017/01027) for supporting us in this work.References

1. Hiremath CS, Sagar KJV, et. al. Emerging behavioral and neuroimaging biomarkers for early and accurate characterization of autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021 Jan 13;11(1):42.2. Wang SS, Kloth AD, Badura A. The cerebellum, sensitive periods, and autism. Neuron. 2014 Aug 6;83(3):518-32.3. Beversdorf DQ, Manning S, et al. Timing of Prenatal Stressors and Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005; 35: 471-478.4. Courchesne E, Karns CM, et al. Unusual brain growth patterns in early life in patients with autistic disorder: an MRI study. Neurology. 2001 Jul 24;57(2):245-54.5. Bolduc ME, Limperopoulos C. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with cerebellar malformations: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009 Apr;51(4):256-67.6. D'Mello AM, Crocetti D, et al. Cerebellar gray matter and lobular volumes correlate with core autism symptoms. Neuroimage Clin. 2015 Feb 20;7:631-9.7. Ramos TC, Balardin JB, et al. Abnormal Cortico-Cerebellar Functional Connectivity in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2019; 12:74.8. Zhao X, Zhu S, et al. Abnormalities of Gray Matter Volume and Its Correlation with Clinical Symptoms in Adolescents with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022 Apr 1;18:717-730.9. Diedrichsen J. A spatially unbiased atlas template of the human cerebellum. Neuroimage. 2006 Oct 15;33(1):127-38.10. Yushkevich PA, Piven J, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 2006 Jul 1;31(3):1116-28.11. Traut N, Beggiato A, et al. Cerebellar Volume in Autism: Literature Meta-analysis and Analysis of the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange Cohort. Biol Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;83(7):579-588.12. Sabuncu MR, Ge T, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Morphometricity as a measure of the neuroanatomical signature of a trait. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Sep 27;113(39):E5749-56.13. Webb SJ, Sparks BF, et al. Cerebellar vermal volumes and behavioral correlates in children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009 Apr 30;172(1):61-7.14. Courchesne E, Campbell K, Solso S. Brain growth across the life span in autism: age-specific changes in anatomical pathology. Brain Res. 2011 Mar 22;1380:138-45.15. Scott JA, Schumann CM, et al. A comprehensive volumetric analysis of the cerebellum in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2009 Oct;2(5):246-57.16. Sathyanesan A, Zhou J, et al. Emerging connections between cerebellar development, behaviour and complex brain disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019 May;20(5):298-313.17. Donovan AP, Basson MA. The neuroanatomy of autism - a developmental perspective. J Anat. 2017 Jan;230(1):4-15.Figures

Figure 1: A representative T1-weighted coronal image demonstrating the cropped cerebellar structure from the cerebrum (A). Fig. B demonstrates the segmented cerebellar lobules overlaid on the cropped cerebellum. Fig. C shows the 3D mesh from the segmented lobules.

Table 1: Showing demographic details and scores of behavioral and developmental assessments from the participants.

Table 2: Comparison of cerebellar lobular volumes between ASD, ASD-siblings, and healthy controls.

Table 3: Pearson correlation between lobular volumes and neurodevelopmental scores in children with ASD

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5316