5302

The Circulatory Arrest Recovery Ammonia Problem (CARAP) Hypothesis1Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Cardiothoracic Surgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neonatal, Spectroscopy, brain, cardiopulmonary bypass, neuronal injury, surgery

Brain injury remains an ongoing concern for patients requiring cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery. Observations in a neonatal pig model of build-up of blood ammonia levels may be a significant unrecognized source of metabolic stress in these surgeries. Ammonia entering the brain upon restarting the CPB pump appears highly correlated with the level of hypothermia and glutamine/glutamate appears highly correlated with brain lactate levels. These changes are also strongly dependent on the choice of surgical parameters such the use of deep hypothermia cardiac arrest (whereby all blood flow is stopped) versus antegrade cerebral perfusion (whereby brain blood flow is maintained).

Introduction

Congenital heart disease affects 1% of US births, with many babies requiring major surgery, resulting in ~50% of the more critical patients suffering from neurological impairment or developmental delay. Hypothermia is commonly used, but optimal surgical parameters to minimize potential neuronal injury are yet unknown [1]. Here, we use 1H MRS and blood ammonia assays in a neonatal pig model to compare two surgical approaches: deep hypothermia cardiac arrest (DHCA) and antegrade cerebral perfusion (ACP).Methods

Two-week old piglets were put on a cardiopulmonary bypass pump and placed in a GE MR750 3T scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with a 16-channel knee coil to study brain metabolism during CPB surgery. Single-voxel MRS data were acquired from a 12x12x15-mm3 right midbrain voxel continuously for approximately three hours using sLASER (TE/TR=30ms/2s, 5000Hz bandwidth, 4096 data points, 64 averages/acquisition) [2]. Brain temperature was monitored via the chemical shift difference between water and NAA. The distribution of animals in terms of surgical protocol and temperature were as follows: DHCA 18ºC (N=6) animals) DHCA 28ºC (N=7), ACP 18ºC (N=1), ACP 28ºC (N=1) and ACP 30ºC (N=2). For the purposes of analysis presented here, data from the ACP 28º and ACP 30ºC animals were combined and labeled “ACP 28ºC”. After brain temperature equilibrated at the hypothermic target, the pump was turned off for 45-55 minutes of circulatory arrest (CA). For DHCA, all blood flow was stopped during this period, whereas, in ACP, blood flow was stopped to the body but maintained to the brain. The pump was then restarted and warming initiated until the brain temperature reached 37°C. Based on 1H MRS findings suggesting the presence of brain ammonia (see Results), a second cohort of piglets under when analogous surgeries outside of the magnet to allow regular blood sampling with ammonia assays. The distribution of animals for this cohort were: DHCA 18ºC (N=1) animals) DHCA 28ºC (N=7), ACP 18ºC (N=1), ACP 28ºC (N=1) and ACP 30ºC (N=2). The blood samples were centrifuged and then assayed for ammonia using a VITROS 250 Chemical System (GMI Lab Solutions, Ramsey, MN).Results

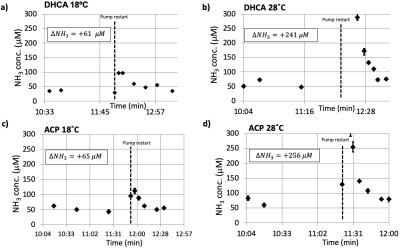

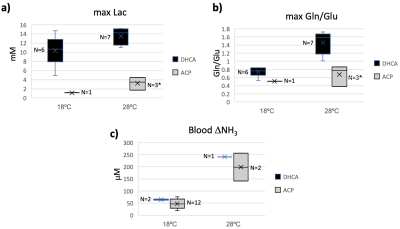

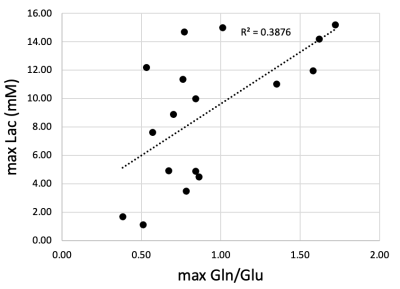

Figure 1 shows the experimental setup and typical data acquisition times. Spectra were reconstructed with eddy-current correction, coil-combination, and pure water spectrum subtraction, and then quantified via LCModel.2 Representative findings for the time evolution of lactate (Lac), glucose (Glc), and the glutamine to glutamate ratio (Gln/Glu) acquired under DHCA or ACP at 18ºC and 28ºC are shown in Figure 2. Given the brain’s primary method for processing ammonia is via the conversion of Glu to Gln, we found the Gln/Glu ratio to be the most informative metric . Representative blood ammonia measurements for the parallel non-MRI 18ºC and 28ºC DHCA and ACP studies are shown in Figure 3, and findings summarized in Figure 4.During DHCA, there was a blood glucose dependent increase in Lac during CA. Elevated Gln/Glu ratios were also observed, starting ~30 min post-CA, whereas ACP studies showed minimal metabolic changes. In contrast, both DHCA and ACP showed similar temperature-dependent blood ammonia levels, peaking immediately upon restarting the CPB pump at end CA, before returning to baseline levels ~20 min later.

Discussion

Whereas elevated lactate was expected during circulatory arrest when there is lack of oxygenated blood reaching the brain [3], the finding of increased brain Gln and decreased in brain Glu (as measured by the Gln/Glu ratio) observed during recovery from CA was not. The increase in Gln/Glu during recovery was dependent on CA-temperature. Blood ammonia increases during recovery from CA, and this increase is dependent on CA-temperature. This led us to the CARAP hypothesis: ammonia production dominated by anerobic gut bacteria, and unlikely to be impacted by CA hypoxia. Ammonia production, however, should be CA-temperature dependent, and ammonia trapped in the gut during CA generates a recovery-bolus that overwhelms the livers capacity to process when blood flow is restarted. Brain effects, however, are observed in DHCA but not ACP, leading to a second lactate-ammonia-glutamine (LAG) hypothesis. Namely, Gln to Glu conversion may be related to blood/brain pH differences as impacted by the high brain lactate formed during DHCA. The blood-brain distribution of ammonia is dependent on the relative pH of blood and brain [4]. Although the increased brain Gln/Glu appears to be linked to both elevated Lac and ammonia in this study, elevated Gln has been observed during ammonia infusion in the absence of elevated lactate [5], and elevated brain lactate could generate an increased blood-brain pH differential, trapping ammonia in brain, yielding an increase in brain Gln/Glu. This would also explain normal Gln/Glu levels during ACP recovery, since ACP avoids this lactate build up.Given the toxicity of ammonia to the developing brain [6], if confirmed in human studies, temperature-dependent build-up of brain ammonia during recovery from CA may represent a previously unreported source of significant metabolic stress during CBP surgery. Areas of ongoing investigation include the effects of blood glucose levels on CA ammonia production and approaches to ameliorate this metabolic stress via methods such as ammonia detoxifying drugs, purging of gut bacteria prior to surgery, or presurgical diet restricts of protein intake.

Acknowledgements

NIH grant R01HL152757, the Lucas Foundation, and GE Health Care.References

- Andropoulos, D.B., et al., Neurologic Injury in Neonates Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Clin Perinatol, 2019. 46(4): p. 657-671.2.

- Spielman, D.M., et al., Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment of neonatal brain metabolism during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. NMR Biomed, 2022. 35(9): p. e4752.3.

- Hanley, F.L., et al., Comparison of dynamic brain metabolism during antegrade cerebral perfusion versus deep hypothermic circulatory arrest using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2020. 160(4): p. e225-e227.4.

- Cooper, A.J. and F. Plum, Biochemistry and physiology of brain ammonia. Physiol Rev, 1987. 67(2): p. 440-519.5.

- Cudalbu, C., et al., Cerebral glutamine metabolism under hyperammonemia determined in vivo by localized (1)H and (15)N NMR spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2012. 32(4): p. 696-708.6.

- Braissant, O., V.A. McLin, and C. Cudalbu, Ammonia toxicity to the brain. J Inherit Metab Dis, 2013. 36(4): p. 595-612.

Figures

Figure 1. a) Experimental setup and timing. b) Representative single-voxel 1H MRS spectra from representative DHCA (top) and ACP (bottom) studies along with associated metabolite concentration vs time curves computed using LCModel fitting.

Figure 2. Representative 1H MRS findings for the time evolution of lactate (Lac) and glucose (Glc), concentrations and the glutamine to glutamate (Gln/Glu) ratio acquire using DHCA or ACP at 18ºC and 28ºC.

Figure 3. Representative blood ammonia measurements for DHCA (a and b) vs ACP (c and d) at 18ºC and 28ºC. An increase in ammonia is observed following the restart of the CPB pump, with this increase larger at higher surgical temperatures. Both ACP and DHCA generate similar amounts of ammonia, consistent with the CARAP hypothesis whereby ammonia is generated by gut bacteria during the circulatory arrest period.

Figure 5. Peak brain lactate (Lac) versus peak brain glutamine to glutamate (Gln/Glu) ratio values showing positive correlation between Gln/Glu elevation and brain lactate levels.