5297

Hippocampal subfield alterations and working memory in children with congenital heart disease1University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2Child Development Center, University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 3Cardiology, University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Segmentation

Reduced hippocampal volumes are associated with working memory impairments in children with congenital heart disease (CHD). However, the volumes of individual hippocampal subfields are largely unexplored in the context of different working memory domains in CHD. In 57 children with complex CHD and 82 age-matched control children, the CHD group showed smaller hippocampal subvolumes, particularly for the hippocampal tail, and poorer verbal and spatial working memory scores, which were differentially related to the hippocampal subvolumes. In addition, hippocampal volumes in cyanotic CHD were significantly smaller than in acyanotic CHD, supporting the link between hypoxia, hippocampal damage, and memory impairment.Introduction

Children and adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) are at risk of structural brain abnormalities including reduced brain volumes.1 While volumetric changes have been related to a variety of cognitive outcomes, one of the most consistent findings has been an association between reduced hippocampal volumes and memory impairment.2 The hippocampus is a complex medial temporal lobe structure which is involved in the processing of semantic, episodic, and spatial memory,3 as well as in learning, emotion, and behaviour4. It is divided into subregions which are thought to be involved in different memory functions.5,6 Most previous studies investigating hippocampal alterations in CHD have examined the volume of the whole hippocampus rather than individual subfields,7-9 or have used self-report scores or composite memory indices to explore brain-behaviour relationships.9,10 Memory is a broad construct with different domains which may relate differentially to different hippocampal subfields, but the link between hippocampal subfield volumes and specific memory domains remains largely unexplored in CHD. The purpose of this study was to examine the association between hippocampal subfield volumes and verbal and spatial working memory, in a cohort of children and adolescents with complex CHD compared to age-matched control children.Methods

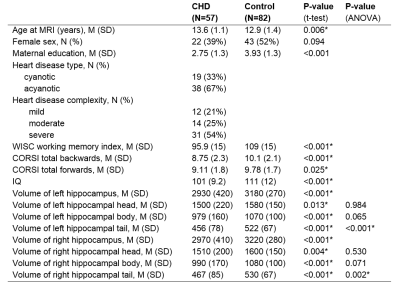

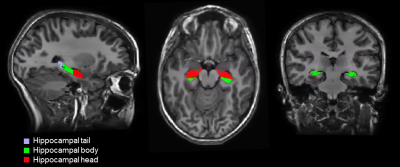

The participant group included 57 children with complex CHD without genetic comorbidities, who had undergone cardiopulmonary bypass surgery before the age of 6 years, and 82 healthy control children (see table 1 for demographics). Verbal working memory was assessed with the working memory index from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children (WISC-IV), and visuo-spatial working memory was assessed from the CORSI block-tapping test. High resolution, 3D T1-weighted cerebral MRI data were collected with a 3T GE MR750 MRI scanner, using an inversion-recovery prepared, spoiled gradient echo volume (IR-SPGR) with TI/TE/TR= 600/5/11 ms and a voxel resolution of 1x1x1mm3. The 3D IR-SPGR data were segmented with FreeSurfer version 7.111, including an automated hippocampal subfield segmentation (Figure 1).12 The volume of the left and right hippocampal head, body, and tail were extracted, and groupwise differences in the volume of these subregions were tested with unpaired t-tests and a univariate ANOVA, with group (CHD vs control) as the fixed factor, covarying for the total brain volume (TBV). Within the CHD group, post-hoc analyses were performed to assess the effect of cyanotic vs acyanotic CHD on the volumes of the hippocampal subregions, covarying for TBV. Associations between working memory measures and hippocampal volumes were tested with partial Spearman correlations, covarying for the group allocation (CHD/control) and TBV. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 27.Results

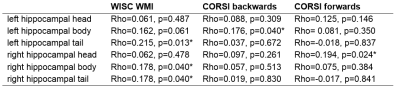

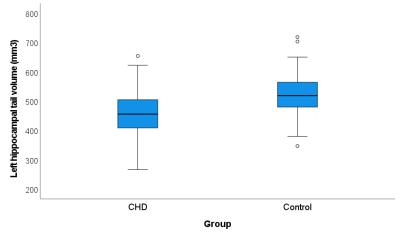

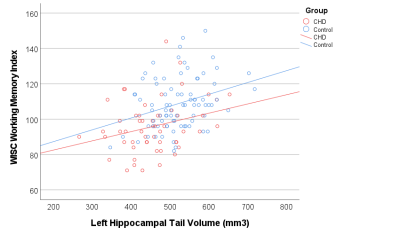

The volumes of the left and right hippocampal head, body, and tail were significantly smaller in the patient group (table 1), but only the hippocampal tail showed a significant groupwise difference after controlling for total brain volume (left hippocampal tail: p<0.001, right hippocampal tail: p=0.002). Within the CHD group, patients with cyanotic CHD had significantly smaller volumes of the left and right hippocampal tail (p=0.019, p=0.024, respectively) as well as the right hippocampal body and head (p=0.004, p=0.015, respectively). Across all participants, the volumes of the left hippocampal tail and right hippocampal body and tail were significantly associated with verbal working memory, while the volumes of the right hippocampal head and left hippocampal body were associated with spatial working memory (table 2).Discussion

The hippocampus is a core brain region involved in memory function and is sensitive to hypoxic injury. Infants with complex CHD may be vulnerable to hypoxic hippocampal injury arising during the neonatal and perioperative period. In the present study, the CHD group showed smaller hippocampal volumes and poorer working memory scores, which were differentially related to the hippocampal subvolumes. In addition, hippocampal volumes in patients with cyanotic CHD were significantly smaller than those in patients with acyanotic CHD, lending weight to the suggestion of a causal sequence leading from hypoxia to hippocampal damage and memory impairment8. These observations are consistent with previous reports of an association between regional hippocampal atrophy and working memory deficits5,6 and the selective vulnerability of different hippocampal subfields to hypoxic/ischemic injury.13 Early detection of hippocampal changes may help to identify those children with complex CHD at risk for memory function impairments.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project Number: 32003B_172914).References

1. Bolduc M-E, et al. Dev Med Child Neurol. 60(12):1209-1224 (2018)

2. Aleksonis HA & King TZ. Neuropsychol Rev, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-022-09547-2 (2022)

3. Moskovitch M, et al. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 16 (2): 179-190 (2006)

4. Catani M, et al. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1724–1737 (2013)

5. Coras R, et al. Brain 137(7):1945–1957 (2014)

6. Menzler K, et al. Seizure 87: 94-102 (2021)

7. Latal B, et al. Pediatric Research, 80(4), 531–537. (2016)

8. Muñoz‐López M, et al. Hippocampus. 27(4): 417–424. (2017)

9. Pike NA, et al. Brain Behav 11(2):e01977. (2021)

10. Fontes K, et al. Hum Brain Mapp. 40(12): 3548–3560. (2019)

11. Dale AM, et al. Neuroimage 9, 179-194 (1999)

12. Iglesias, JE, et al. Neuroimage 115:117-137. (2015)

13. Hatanpaa KJ, et al. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 73(2): 136–142. (2014)

Figures