5294

Memory and learning relationships with hippocampal morphometry and multi-modal connectivity after pediatric severe TBI1Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Department of Psychology and Neuroscience Center, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States, 4Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, United States, 5Biostatistics, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 6Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 7Critical Care, Faculty of Medicine, Melbourne University, Melbourne, Australia, 8Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 9Pediatrics, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, United States, 10Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Traumatic brain injury

Traumatic brain injury in adolescents is a major public health concern, leading to tens of thousands of hospitalizations in the U.S. each year. Our study aims to identify multimodality imaging biomarkers of long-term neurocognitive outcome after severe adolescent TBI. For this investigation we explored memory performance using the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) in relation to structural and functional connectivity of the memory network, as well as hippocampal volume and fornix microstructure.

Introduction

From a quantitative neuroimaging perspective, the volume of the hippocampus as a marker of hippocampal damage has been consistently related to various memory deficits, especially in severe TBI. The relationship is however not exceptionally robust1–3. The memory network is complex including not only the hippocampus, but fornix, mammillary bodies, anterior thalamic projections and aspects of the cingulum bundle4. Furthermore, the hippocampus is a structure that interfaces with all primary sensory and motor cortical regions as well as association cortices and therefore, poses a complex neural structure throughout the brain5–7. In terms of TBI-induced hippocampal pathology, a multimodality neuroimaging approach is most appropriate as it takes into account not only the target structure, but also the neural network associated with the hippocampus8. As such, in the current study we employed anatomical as well as structural and functional neuroimaging analyses that examined the memory network in relation to neuropsychological learning and memory performance on the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT-C/II) in children recovering from severe traumatic brain injury and typically developing controls.Methods

Twenty-two adolescents with severe TBI (Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8) enrolled in the Approaches and Decisions in Acute Pediatric TBI (ADAPT) study were recruited for multimodal MRI scanning 1-2 years post-injury at 13 participating sites. A typically developing (TD) control cohort of 49 age-matched children also underwent scanning and neurocognitive assessment. Brain imaging was performed using 3T MRI standardized neuroimaging protocols across several sites. T1-weighted, T2-weighted, T2-weighted FLAIR, T2*-weighted, diffusion tensor (DTI), and resting state functional MRI (fMRI) data were obtained for each subject. Manufacturer-specific protocols were harmonized to conform to protocols similar to the multi-site Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in TBI (TRACK-TBI) study.Hippocampal volume was derived from segmentations of the T1-weighted images using FreeSurfer9. Mean fractional anisotropy (FA) was sampled from fornix segmentations obtained using TractSeg10, which uses a pre-trained convolutional neural network to create region-specific tractograms.

Functional connectivity of hippocampus was computed by first averaging pre-processed fMRI data over hippocampus masks, and then computing the temporal Pearson’s correlation with all other voxel time series. The network of brain regions significantly connected to each hippocampus (“hippocampal network”) was determined by computing a 1-sample t-test of the Fisher-Z transformed voxel-wise connectivity maps in the control subjects. Voxels where the group-level functional connectivity exceeded a Bonferroni corrected p-value of 0.05 were considered to be significantly connected. The hippocampal functional connectivity in each TBI subject was then averaged over each hemisphere’s hippocampal network (defined by the control subjects).

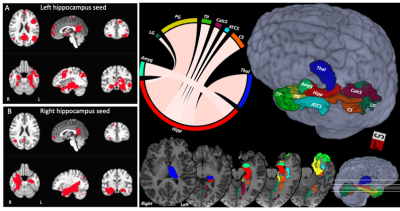

The hippocampus-specific structural connectome was derived by first producing individual connectomes using SIFT2-filtered probabilistic whole-brain fiber tracking off fODF maps11,12 combined with 164 cortical and subcortical gray matter regions based on the Destrieux atlas 9,13. The measure of structural connectivity was chosen to be the fiber bundle capacity (FBC), which represents the ability of a white matter pathway to carry information14. Then, full-brain structural connectomes were averaged across participants in the TD group. Subsequently, hippocampus specific connectivity was extracted from the mean connectome representing only those connections to or from the hippocampus. The resulting connectome was then sorted in descending order with respect to connectivity values. Finally, the top 5% connections were selected to form the hippocampus connectome. This definition was used to study connectivity in the TBI cohort as well.

Results

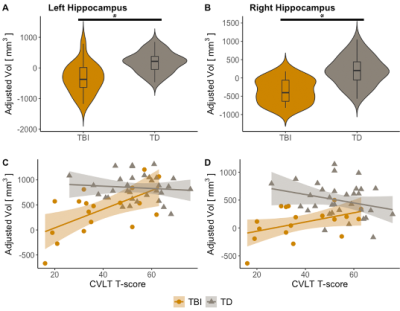

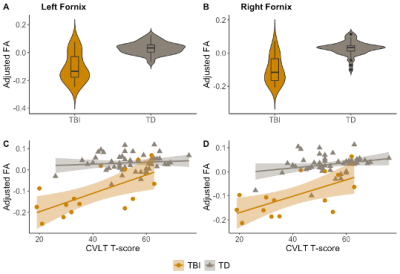

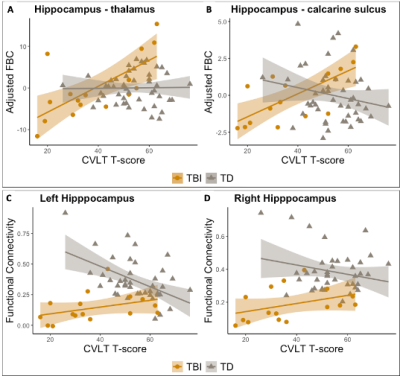

Results showed hippocampus volume was decreased in TBI with respect to controls (Figure 3, A-B). Further, hippocampal volume loss (left and right) was associated with worse performance on CVLT in TBI subjects (Figure 3, C-D). Similarly, hippocampal fornix fractional anisotropy (FA) was reduced in TBI with respect to controls (Figure 4, A-B), while decreased FA in the hippocampal fornix (left and right) also was associated with worse performance on CVLT in TBI subjects (Figure 4, C-D). Additionally, reduced structural connectivity of left hippocampus to thalamus and calcarine sulcus was associated with CVLT in TBI subjects (Figure 5, A-B). Functional connectivity in the left hippocampal network was also associated with CVLT in TBI subjects (Figure 5, C-D).Discussion

Advanced neuroimaging methods have become important to examine where a specific TBI-induced lesion or focal abnormality may be identified as well as to how neural networks are impaired15–17. Following the use of an assortment of those methods, the current investigation demonstrates that memory performance relates to the integrity of the entire memory network, not just a single component. Most importantly, these regional findings from a multi-modal MRI approach should not only be useful for gaining valuable insight into TBI-induced memory and learning disfunction, but may also be informative for monitoring injury progression, recovery, and for developing rehabilitation as well as therapy strategies.Acknowledgements

Funding

Support for this work was provided by the UW-Madison Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, and NIH grant U01 NS081041 (Bell) and RO1 NS092870 (Ferrazzano). This study was also supported in part by a core grant to the Waisman Center from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development P50HD105353. JG’s effort was supported in part by the Medical Physics Radiological Sciences Training Grant NIH T32 CA009206. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ADAPT MRI Biomarkers Investigators

The ADAPT MRI Biomarkers Investigators are: Warwick Butt, Melbourne, Australia; Ranjit Chima, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; Robert Clark, University of Pittsburgh; Nikki Ferguson, Virginia Commonwealth University; Mary Hilfiker, UC-San Diego; Kerri LaRovere, Boston Children’s; Iain Macintosh, Southampton, UK; Darryl Miles, University of Texas Southwestern; Kevin Morris, Birmingham, UK; Nicole O’Brien, Nationwide Children’s Hospital; Jose Pineda, Washington University; Courtney Robertson, Johns Hopkins University; Karen Walson, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta; Nico West, University of Tennessee; Anthony Willyerd, Phoenix Children’s Hospital; Brandon Zielinski, University of Utah Primary Children’s; Jerry Zimmerman, Seattle Children’s Hospital.

References

1. Bigler, E. D. et al. Hippocampal volume in normal aging and traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 18, 11–23 (1997).

2. Himanen, L. et al. Cognitive functions in relation to MRI findings 30 years after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 19, 93–100 (2005).

3. Tomaiuolo, F. et al. Gross morphology and morphometric sequelae in the hippocampus, fornix, and corpus callosum of patients with severe non-missile traumatic brain injury without macroscopically detectable lesions: a T1 weighted MRI study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 75, 1314–1322 (2004).

4. Budson, A. E. & Price, B. H. Memory dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 692–699 (2005).

5. Ekstrom, A. D. & Ranganath, C. Space, time, and episodic memory: The hippocampus is all over the cognitive map. Hippocampus 28, 680–687 (2018).

6. Lavenex, P. & Amaral, D. G. Hippocampal-neocortical interaction: a hierarchy of associativity. Hippocampus 10, 420–430 (2000).

7. Raut, R. V., Snyder, A. Z. & Raichle, M. E. Hierarchical dynamics as a macroscopic organizing principle of the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 20890–20897 (2020).

8. Irimia, A. et al. Traumatic Brain Injury Severity, Neuropathophysiology, and Clinical Outcome: Insights from Multimodal Neuroimaging. Front. Neurol. 8, 530 (2017).

9. Fischl, B. et al. Whole Brain Segmentation. Neuron 33, 341–355 (2002).

10. Wasserthal, J., Neher, P. & Maier-Hein, K. H. TractSeg - Fast and accurate white matter tract segmentation. NeuroImage 183, 239–253 (2018).

11. Smith, R. E., Tournier, J.-D., Calamante, F. & Connelly, A. SIFT2: Enabling dense quantitative assessment of brain white matter connectivity using streamlines tractography. NeuroImage 119, 338–351 (2015).

12. Tournier, J.-D. et al. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. NeuroImage 202, 116137 (2019).

13. Destrieux, C., Fischl, B., Dale, A. & Halgren, E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. NeuroImage 53, 1–15 (2010).

14. Smith, R., Raffelt, D., Tournier, J.-D. & Connelly, A. Quantitative streamlines tractography: methods and inter-subject normalisation. https://osf.io/c67kn (2020) doi:10.31219/osf.io/c67kn.

15. Gordon, E. M. et al. Three Distinct Sets of Connector Hubs Integrate Human Brain Function. Cell Rep. 24, 1687-1695.e4 (2018).

16. Rangaprakash, D. et al. Identifying disease foci from static and dynamic effective connectivity networks: Illustration in soldiers with trauma. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 264–287 (2018).

17. Yan, H., Feng, Y. & Wang, Q. Altered Effective Connectivity of Hippocampus-Dependent Episodic Memory Network in mTBI Survivors. Neural Plast. 2016, 6353845 (2016).

Figures

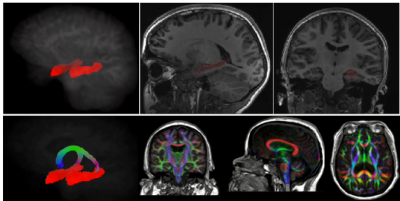

Hippocampus and fornix example segmentations. Top panel: segmentation of hippocampus embedded and overlaid in T1 weighted image. Bottom panel: segmentation of the fornix and directionally color-coded fractional anisotropy (FA) embedded in T1-weighed image.

Fornix FA by group and memory performance. A-B, group comparison of left and right fornix FA between TBI (yellow) and control cohort (gray), adjusted for age and sex; *p<0.05. C-D, left and right fornix FA as a function of CVLT T-score for TBI (yellow) and control cohorts (gray), adjusted for age and sex.

Hippocampal connectivity and CVLT . Top panel: Correlation between structural connectivity and memory performance. Fiber bundle capacity (FBC) as a function of CVLT T-score for TBI (yellow) and control cohort (gray), adjusted for age and sex, for hippocampus with thalamus (A) and with calcarine sulcus (B). Bottom panel: Association between hippocampus functional network connectivity (FC) and memory performance for left (C) and right (D) hippocampi. Spearman rank correlation between Hippocampal FC and CVLT T-score is shown for TBI (yellow) and control (gray) subjects.