5293

Glutamate in the visual cortex changes within the migraine cycle in children and adolescents

Lydia Y Cho1,2,3, Tiffany K Bell1,2,3, Kate J Godfrey1,2,3, Andrew D Hershey4,5, Jonathan Kuziek2,3,6, Mehak Stokoe1,2,3, Kayla Millar1,2,3, Serena L Orr2,3,6, and Ashley D Harris1,2,3

1Department of Radiology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 3Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 4Division of Neurology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States, 5Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati School of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, United States, 6Departments of Pediatrics, Community Health Sciences, and Clinical Neurosciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

1Department of Radiology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 3Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 4Division of Neurology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States, 5Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati School of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, United States, 6Departments of Pediatrics, Community Health Sciences, and Clinical Neurosciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Spectroscopy, Migraine

Migraine is a common neurological disorder in pediatrics, yet the pathophysiology remains unclear. Migraine is characterized by episodic attacks, suggesting a shifting excitation-inhibition imbalance that when tipped, will trigger an attack. We used magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentrations to examine changes in these brain metabolites across different phases of the migraine attack in children and adolescents. We show fluctuations in glutamate with migraine cycle phases in the visual cortex. There were no observed changes in glutamate nor GABA in the sensorimotor cortex and the thalamus.Introduction

Migraine is a major cause of disability worldwide, with a prevalence of approximately 8% in children and adolescents1. Symptoms associated with migraine in children, such as headaches, nausea, and sensory sensitivity, decrease quality of life and cause disability in the home, school, and extracurricular domains2,3. Despite its high prevalence, the pathophysiology of migraine is not clear.Migraine is characterized by episodic attacks (ictal period) with phases that include: prodrome, aura, headache, and postdrome. However, the majority of studies are done during attack free times (interictally) at a single time point. The few studies that have investigated the interictal and ictal periods in adults have suggested an excitation-inhibition imbalance in the brain that fluctuates during the phases, including cortical hyperexcitability during the headache phase4,5, suggesting glutamate (excitatory neurotransmitter) and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA; inhibitory neurotransmitter) as candidates for further investigation. However, there have been no studies observing the migraine cycle in children and adolescents. These types of studies are crucial for better insight into the pathophysiology of migraine.

This project uses advanced proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to examine how glutamate and GABA concentrations fluctuate throughout the attack in children and adolescents.

Methods

Twenty-three participants (6M/17F) aged 10-17 years with migraine (with or without aura) were recruited. All individuals completed four appointments within a two-week period.Each participant completed baseline headache characterization questionnaires prior to the first appointment. For the duration of their participation, participants completed daily headache diaries to record headache occurrence and duration.

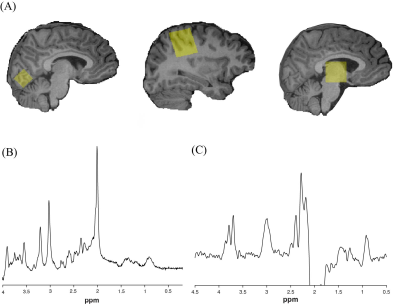

Data were collected at 3T (MR750w, General Electric). Each scan session began with a T1-weighted anatomical image for voxel placement and segmentation (BRAVO; 230 slices, TR/TE = 7.4/2.7 ms, 0.8 mm3 isotropic voxels). GABA was measured in the thalamus and right sensorimotor cortex using macromolecule-suppressed GABA-edited MRS6 (TR/TE = 1800/80 ms, 20 ms editing pulses applied at 1.5 and 1.9 ppm, 256 averages, 3x3x3 cm3 voxel). A short-echo time Point RESolved Spectroscopy (PRESS) acquisition (TR/TE = 1800/30 ms, 64 averages) was also acquired in the same voxels. Additionally, PRESS data were also acquired in a 2x2x2 cm3 voxel in the visual cortex. GABA data was preprocessed and analyzed using Gannet 3.27. PRESS data was preprocessed and analyzed using FID-A8 and LCModel9. Data were cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-corrected while accounting for tissue specific relaxation. The α-correction method10 was additionally applied to GABA data to account for twice the amount of GABA being present in grey matter compared to white matter.

Relationships between brain metabolite concentrations and attack phase were explored using linear mixed effect models. Scans were binned into phases as prodrome (within 24 hours before headache), headache, postdrome (within 24 hours after headache), or interictal (more than 24 hours before or after headache). Two models were generated to test the relationship between brain metabolite concentrations and migraine phase: (1) time leading to an attack (phases ordered as “Interictal”, “Prodrome”, and “Headache”) and (2) time following an attack (phases ordered as “Headache”, “Postdrome”, and “Interictal”). Age and sex were included as fixed effects and subject was included as a random effect to account for repeated measures.

Results

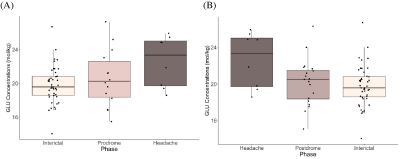

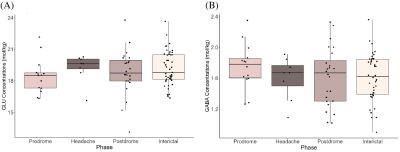

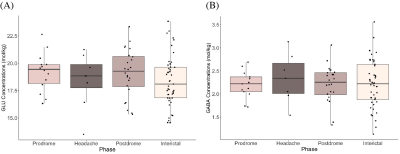

Figure 2 shows boxplots of visual cortex glutamate concentrations. Concentrations increased leading up to the headache phase and decreased after the headache phase (Figure 2). Model 1 (pre-headache) showed a significant effect of phase on glutamate levels, with levels increasing leading up to the headache (βphase = 1.29, 95% CI [1.01, 1.57], tphase(57) = 2.72, p = .009). In Model 2 (following headache), there was a significant effect of phase on glutamate, with levels decreasing following the headache (βphase = -1.06, 95% CI [-1.34, -0.78], tphase(61) = -2.46, p = .017).There were no significant effects of phase on glutamate or GABA levels in the sensorimotor cortex (Figure 3) and thalamus (Figure 4).

Discussion

Results suggest region-specific changes in glutamate across the migraine attack. Specifically, in the visual cortex, glutamate levels increase leading up to the headache phase and decrease following the headache. The occipital cortex is implicated in migraine pathophysiology and seen to be hyperresponsive in individuals with migraine11. It is the originating location of cortical spreading depression, the most likely neurophysiological correlate of aura12. Therefore, the increase in glutamate during the headache phase supports the suggestion that cortical hyperexcitability may contribute to the pathophysiology of migraine.In conclusion, changes in glutamate throughout the migraine cycle in children and adolescents were observed. While further exploration is required, this provides novel insight into the unique pathophysiology of migraine in children and adolescents, while opening avenues for treatment targets for this patient population.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Research was supported by a Sick Kids Foundation New Investigator Award, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. A D Harris holds a Canada Research Chair in MR Spectroscopy in Brain Injury.References

1. Abu-Arafeh I, Razak S, Sivaraman B, Graham C. Prevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies: Review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2010;52(12):1088–1097.2. Vannatta K, Getzoff EA, Gilman DK, et al. Friendships and social interactions of school-aged children with migraine. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(7):734–743.

3. Rocha-Filho PAS, Santos PV. Headaches, Quality of Life, and Academic Performance in Schoolchildren and Adolescents. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2014;54(7):1194–1202.

4. Cortese F, Coppola G, Di Lenola D, et al. Excitability of the motor cortex in patients with migraine changes with the time elapsed from the last attack. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):2.

5. Cosentino G, Fierro B, Vigneri S, et al. Cyclical changes of cortical excitability and metaplasticity in migraine: evidence from a repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Pain. 2014;155(6):1070–1078.

6. Harris AD, Puts NAJ, Barker PB, Edden RAE. Spectral-editing measurements of GABA in the human brain with and without macromolecule suppression: Relationship of GABA+ and MM-suppressed GABA. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74(6):1523–1529.

7. Edden RAE, Puts NAJ, Harris AD, Barker PB, Evans CJ. Gannet: A batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid-edited MR spectroscopy spectra: Gannet: GABA Analysis Toolkit. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40(6):1445–1452.

8. Simpson R, Devenyi GA, Jezzard P, Hennessy TJ, Near J. Advanced processing and simulation of MRS data using the FID appliance (FID‐A)—An open source, MATLAB‐based toolkit. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(1):23–33.

9. Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30(6):672–679.

10. Harris AD, Puts NAJ, Edden RAE. Tissue correction for GABA-edited MRS: Considerations of voxel composition, tissue segmentation, and tissue relaxations: Tissue Correction for GABA-Edited MRS. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(5):1431–1440.

11. Barbanti P, Brighina F, Egeo G, Di Stefano V, Silvestro M, Russo A. Migraine as a Cortical Brain Disorder. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2020;60(9):2103–2114.

12. Zhang L, Huang J, Zhang Z, Cao Z. Altered Metabolites in the Occipital Lobe in Migraine Without Aura During the Attack and the Interictal Period. Front Neurol. 2021;12:656349.

Figures

Figure 1. (A) Voxel placement in visual cortex, right sensorimotor cortex, and thalamus (left to right). (B) Example of glutamate PRESS data from sensorimotor cortex quantified using LCModel. (C) Example of macromolecule-suppressed GABA-edited MRS data from sensorimotor cortex quantified using Gannet.

Figure 2. Boxplots showing glutamate concentrations (mol/kg) in the visual cortex (A) leading up to headache phase (Model 1) and (B) following headache phase (Model 2).

Figure 3. (A) Glutamate concentrations (mol/kg) and (B) GABA concentrations (mol/kg) across migraine phases (prodrome, headache, postdrome, and interictal) in the sensorimotor cortex.

Figure 4. (A) Glutamate concentrations (mol/kg) and (B) GABA concentrations (mol/kg) across migraine phases (prodrome, headache, postdrome, and interictal) in the thalamus.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5293