5292

Adapting the NODDI-GBSS Framework for the 1-Month Infant Brain

Marissa DiPiero1,2, Patrik Goncalves Rodrigues2, Hassan Cordash2, Jose Guerrero Gonzalez2, Richard J. Davidson3,4,5, Andrew Alexander2,3,6, and Douglas C. Dean III2,6,7

1Neuroscience Training Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 5Center for Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 6Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 7Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

1Neuroscience Training Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 5Center for Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 6Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 7Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Gray Matter

The brain’s cytoarchitecture undergoes highly dynamic morphological changes during early life that establish the brain’s structural and functional framework and lays the foundation for future cognitive and behavioral skills. While differences in early cortical organization are thought to subserve future behavioral and psychiatric challenges, little is known regarding cortical organization in early life. For the first time, we adapt the NODDI-GBSS framework for the infant brain while keeping the data in its native diffusion space. We show feasibility for cortical skeletonization and show relationships with age across the GM microstructure within the first month of life.Introduction

The neurodevelopmental epoch from fetal stages to early life embodies a critical window of peak growth and plasticity in which differences believed to be associated with many neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders first emerge1-6. Obtaining a detailed understanding about the developmental patterns of the cortical gray matter (GM) microstructure is necessary to characterize differential patterns of neurodevelopment that may subserve future intellectual, behavioral, and psychiatric challenges. The Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density (NODDI) Gray-Matter Based Spatial Statistics (NODDI-GBSS)7, 8 framework enables sensitive characterization of the gray matter microstructure, while limiting partial voluming and misregistration issues between images collected in different spaces. However, limited contrast and poor tissue segmentation in the developing brain creates challenges for implementing the NODDI-GBSS framework on infant diffusion MRI (dMRI) data. Currently, two other studies have used GBSS to assess cortical microstructure for the infant brain9, 10, however, these studies relied on structural imaging for tissue segmentation and spatial normalization. Here, we aim to refine the NODDI-GBSS framework for the 1-month brain while keeping the dMRI data entirely in native space for processing and analysis, a method that has not been accomplished previously. Taking this approach, we cross-sectionally investigate age-relationships in the developing GM microstructural organization in infants within the first month of life.Methods

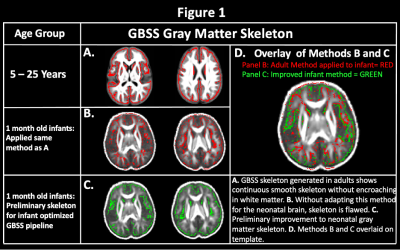

Multishell dMRI data were acquired from 34 1-month old infants on a 3-T scanner (MR750 Discovery scanner; General Electric) equipped with a 32-channel head coil (Nova Medical). A three-shell protocol was acquired in 9/18/36 diffusion-encoding gradient directions at b = 350/800/1500 s/mm2, respectively, and 6 with no (b = 0 s/mm2) diffusion weighting. Images were corrected for eddy-current distortions and head motion11, Gibbs ringing, and EPI distortions using an in house-processing pipeline and software developed through FSL12 and MRTrix313 and were then fit to the DTI and NODDI14 models.A population template was generated from each subject’s FA maps using Advanced Normalization Tools software suite15 with reference to the 0-to-2-month T2-weighted template from the NIHPD Objective 2 atlases16. The NODDI ODI map was utilized for segmentation to provide improved contrast between tissue types. Based on the reduced average GM fraction values in the 1-month brain compared to adults, an adjusted GM fraction threshold of 0.45 (compared to 0.65 in adults) was used to construct the GM skeleton. We investigated voxel-wise age-relationships with GM along the infant GM skeleton generated with our adapted infant pipeline (Fig. 1C.). Non-parametric permutation testing was carried out using Permutation Analysis of Linear Models (PALM)17, 18 and threshold free cluster enhancement19 were used to identify significant regions at p < 0.05, FWER-corrected within modality and contrast.

Results

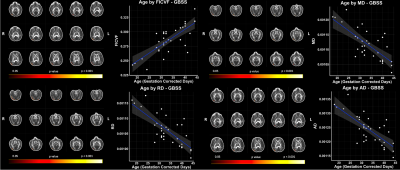

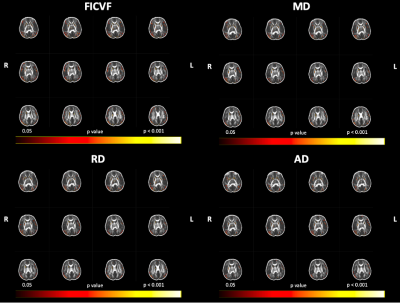

Using our adapted NODDI-GBSS method with enhanced segmentation and atlas-based template construction approach, we improved GM skeletonization in the underdeveloped brain such that the skeleton was specific to the GM and not white matter (WM) and was also more contiguous with the entire cortex when compared to applying the NODDI-GBSS pipeline without modification (Fig. 1C). We propose a robust approach for improved GM skeleton construction in the underdeveloped human brain with sensitivity to age-related organization in GM. We report significant relationships of GM microstructure with age in the first month of life, with FICVF increasing with age, and MD, RD, and AD decreasing with age (p < 0.05; FWE-Corrected) (Fig. 2). Preliminary findings also suggest early age-relationships of the developing GM microstructure across widespread cortical regions (p < 0.05; uncorrected) (Fig.3).Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate feasibility in utilizing the NODDI-GBSS framework to investigate the cortical GM microstructure in infants as young as 1 month of age. Given the limited contrast between GM and WM of the 1-month brain, traditional segmentation using an FA map may result in erroneous and inaccurate GM skeletonization in the NODDI-GBSS framework (Fig. 1B), which can propagate through performed analyses. With our adapted framework, we show improvement of infant cortical skeletonization with improved specificity to the GM compared to applying the NODDI-GBSS pipeline without modification from the adult method (Fig. 1C). We show significant relationships with the developing cortical GM organization and age in occipital brain areas (Fig. 2). Further, we observe relationships with age and the developing GM microstructure in widespread cortical regions, however, these relationships did not survive corrections for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05, uncorrected) likely due to our small sample size (Fig. 3). Future work will examine age-relationships in a larger sample of 1-month infants. Enhanced information about cortical organization from NODDI-GBSS in this age range will improve our understanding and detection of pre-clinical differences underlying future developmental conditions and make room for the development of targeted interventions and therapeutics.Conclusion

The cortical GM microstructure plays a critical role in overall brain function and connectivity. Establishment of the cytoarchitecture in early life lays the groundwork in which future cognitive and behavioral skills are built upon, with differences in early cortical organization thought to subserve future behavioral and psychiatric challenges. For the first time, we adapt the NODDI-GBSS for the infant brain while keeping the data in its native diffusion space. We show feasibility of cortical skeletonization in the underdeveloped brain and report relationships with age across the GM microstructure in the first month of life.Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank our research participants and their families who participated in this research as well as the dedicated research staff who made this work possible. This work was supported by grants by the National Institutes of Mental Health (P50 MH100031; Dr. Richard Davidson) and R00 MH11056 (Dr. Douglas Dean) from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health. Infrastructure support was also provided, in part, by grant U54 HD090256 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD, National Institutes of Health (Waisman Center). First author, Marissa DiPiero was also supported in part by NIH/NINDS T32 NS105602.References

1. Rees, S. and T. Inder, Fetal and neonatal origins of altered brain development. Early Human Development, 2005. 81(9): p. 753-761.2. Bale, T.L., et al., Early life programming and neurodevelopmental disorders. Biol Psychiatry, 2010. 68(4): p. 314-9.

3. De Asis-Cruz, J., N. Andescavage, and C. Limperopoulos, Adverse Prenatal Exposures and Fetal Brain Development: Insights From Advanced Fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 2022. 7(5): p. 480-490.

4. Al-Haddad, B.J.S., et al., The fetal origins of mental illness. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2019. 221(6): p. 549-562.

5. Oskvig, D.B., et al., Maternal immune activation by LPS selectively alters specific gene expression profiles of interneuron migration and oxidative stress in the fetus without triggering a fetal immune response. Brain Behav Immun, 2012. 26(4): p. 623-34.

6. Smith, K.E. and S.D. Pollak, Early life stress and development: potential mechanisms for adverse outcomes. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2020. 12(1): p. 34.

7. Nazeri, A., et al., Gray Matter Neuritic Microstructure Deficits in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 2017. 82(10): p. 726-736.

8. Nazeri, A., et al., Functional consequences of neurite orientation dispersion and density in humans across the adult lifespan. J Neurosci, 2015. 35(4): p. 1753-62.

9. Ball, G., et al., Development of cortical microstructure in the preterm human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(23): p. 9541-6.

10. Wang, W., et al., Altered cortical microstructure in preterm infants at term-equivalent age relative to term-born neonates. Cereb Cortex, 2022.

11. Andersson, J.L.R. and S.N. Sotiropoulos, An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage, 2016. 125: p. 1063-1078.

12. Jenkinson, M., et al., Fsl. Neuroimage, 2012. 62(2): p. 782-90.

13. Tournier, J.D., et al., MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage, 2019. 202: p. 116137.

14. Zhang, H., et al., NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage, 2012. 61(4): p. 1000-16.

15. Avants, B.B., N. Tustison, and G. Song, Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight j, 2009. 2(365): p. 1-35.

16. Fonov, V., et al., Unbiased average age-appropriate atlases for pediatric studies. Neuroimage, 2011. 54(1): p. 313-27.

17. Winkler, A.M., et al., Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage, 2014. 92: p. 381-97.

18. Winkler, A.M., et al., Faster permutation inference in brain imaging. NeuroImage, 2016. 141: p. 502-516.

19. Smith, S.M. and T.E. Nichols, Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage, 2009. 44(1): p. 83-98.

Figures

Figure 1: Improvement of NODDI-GBSS Skeleton for the 1-Month Brain.

Figure 2: Significant Age Relationships with GBSS Measures in the 1-Month Brain. Scatter plots represent mean values of voxels significantly associated with age. Color bar indicates level of significance and neuroanatomical location of voxels significantly associated with age.

Figure 3: Age Relationships with GBSS Measures in the 1-Month Brain, Uncorrected for Multiple Comparisons. Color bar indicates level of significance and neuroanatomical location of voxels associated with age, uncorrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5292