5276

Workflow and performance measures for integrating magnetic field monitoring with an 8-channel pediatric head coil for 7T MRI1McConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 3Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4Siemens Healthcare Limited, Montreal, QC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: System Imperfections: Measurement & Correction, RF Arrays & Systems

Ultra-high field MRI is particularly susceptible to dynamic magnetic field fluctuations. To address this, commercial field probes were integrated into an 8-channel dipole Tx/Rx 7 T pediatric head coil. Coil performance was assessed before and after probe integration. Probe performance was compared on and off the coil. After probe integration, reflection coefficients were maintained below -10dB in all channels, noise correlation was shown to improve, and maximum SNR was shown to decrease. Probe performance did not change substantially once mounted on the coil. Future work will aim to address the reduction in SNR observed after probe integration.Introduction

Highly accurate and reproducible 7 Tesla (T) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) requires precise knowledge of the behaviour and spatio-temporal evolution of the magnetic field during image acquisition1. Fluctuations in the dynamic magnetic field caused by system imperfections and subject motion can significantly reduce image quality and reproducibility. The severity of these fluctuations and resultant image reconstruction errors increases with field strength2. We have designed a 7T pediatric head coil with built-in magnetic field monitoring capability using commercial field monitoring probes (Skope Clip-On Camera, Skope Magnetic Resonance Technologies AG, Zurich, CH). Our coil aims to address the increased prevalence of motion artifacts in pediatric MRI and the impact of dynamic magnetic field fluctuations on high resolution 7T brain imaging3.Methods

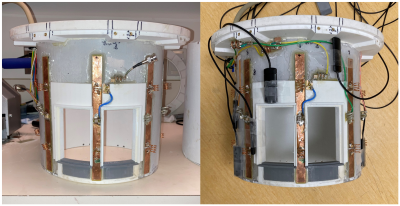

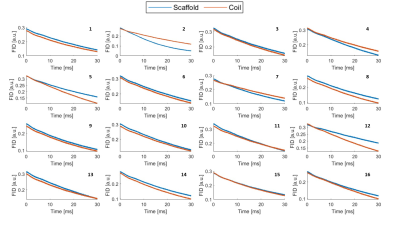

The coil consisted of 8 dipole antennas with dimensions of 205 x 15 mm2. The dipole antennas were mounted onto a cylindrical polycarbonate former (internal diameter = 240 mm) and offset by 45⁰ relative to one another to provide full coverage of the head. Each dipole functioned as a transceiver and was connected to a transmit/receive (Tx/Rx) switch. The specific dipole geometry was optimized using the CST electromagnetic simulation software (CST Studio, Dassault Systems) to produce a highly homogenous B1+ excitation field. The coil was optimized on the lab bench to have reflection coefficients below -15 dB. The dipole elements were advantageous as they offered reduced footprint on the former compared with other element designs, allowing for flexible positioning of the field probes.The Skope Clip-On camera system consisted of 16 19F based NMR field probes4. The probes were positioned between dipole transceivers on the coil former (Figure 1). The resulting free-induction decay (FID) signals from each probe were measured. A goal of this measurement was to ensure the normalized FID signal was above 10% of the initial magnitude at a timepoint 30 ms after the probe radiofrequency (RF) excitation. Once all 16 probes were integrated with the coil, their positions were adjusted to maximize the measured FID signal at t=30ms. The coupling and reflection coefficients of the coil elements were then measured. The coil elements were then retuned using adjustable inductors to achieve reflection coefficients below -10 dB.

The performance of the coil was quantitatively evaluated, with and without field probes, based on Scattering Matrix (S-Matrix) parameters, noise correlation, and SNR by imaging a 120mm diameter cylindrical NiSO4×6H2O doped water phantom using a 7T whole-body MR system (MAGNETOM Terra, Siemens Healthineers). Field probe FID signals were measured with the probes mounted on the Skope probe scaffold (i.e., optimal positioning, no interaction with coil) and mounted on the dipole transceiver coil5.

Results

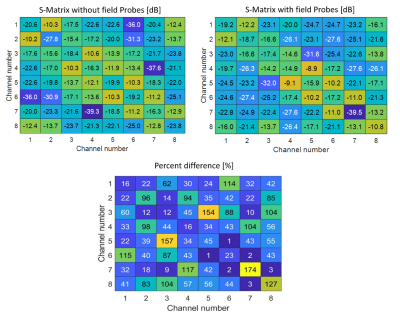

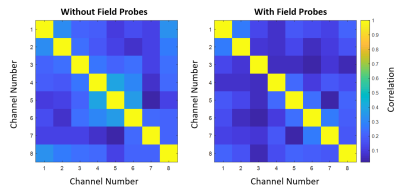

S-parameter matrices for the coil with and without field probes are displayed in Figure 2. Without the probes, all coil elements had reflection coefficients below -15 dB. The worst reflection occurred in channels 4 and 7 (-16.3 dB). After probe integration, all reflection coefficients were measured to be below -10 dB with the worst reflection occurring in channel 8 (-10.8 dB). The mean percent difference in S-parameters between the coil with and without the probes was 52%.Noise correlation matrices measured without and with field probes are displayed in Figure 3. The mean noise correlation decreased from 19% to 12% and the maximum noise correlation decreased from 41% to 28% with the addition of the field probes.

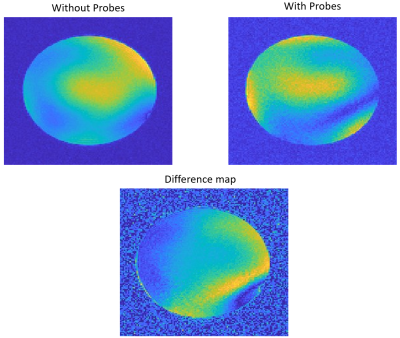

Gradient echo (GRE) images acquired using the pediatric dipole transceiver coil with and without field probes are shown in Figure 4. Both the overall SNR and signal intensity across the phantom were altered with the addition of the field probes. The maximum measured SNR decreased from 37.7 dB to 29.5 dB with the addition of the field probes.

The FID signal for each probe was measured when placed on the Skope scaffold and on the coil (Figure 5). The mean normalized FID signal magnitudes recorded 30 ms after probe excitation on the scaffold and on the coil were 43.8% and 43% of the initial FID magnitude, respectively.

Discussion

We demonstrated the application of a custom-engineered, 8 channel dipole transceiver coil for pediatric 7 T imaging with magnetic field monitoring probes. With the addition of the probes, power reflection remained below -10 dB (Figure 1). Interestingly, the addition of the field probes improved the noise correlation performance of the coil (Figure 2). A reduction in SNR was apparent in GRE images acquired with and without the probes (Figure 4). This may be attributed to the proximity of the field probes to the transceiver elements. The FID decay signal of the field probes on the coil was comparable to the corresponding decay signal observed with the probes mounted on the Skope scaffold.Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate (a) the viability of integrating field monitoring in a 7 T pediatric head coil and (b) a preliminary workflow for optimizing both probe positioning and coil hardware for integrated field monitoring. Future work will address a more concrete optimization procedure for positioning the probes and investigate the application of the dipole transceiver for pediatric human brain imaging.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Paul Weavers from Skope for providing helpful directions in analyzing acquired Skope data. This work was supported by the Transforming Autism Care Consortium, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the McGill Healthy Brains Healthy Lives Initiative.References

1. B. E. Dietrich, D. O. Brunner, B. J. Wilm, C. Barmet, S. Gross, L. Kasper, M. Haeberlin, T. Schmid, S. J. Vannesjo, K. P. Pruessmann, A field camera for MR sequence monitoring and system analysis. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 75, 1831–1840 (2016).

2. Y. Duerst, B. J. Wilm, B. E. Dietrich, S. J. Vannesjo, C. Barmet, T. Schmid, D. O. Brunner, K. P. Pruessmann, Real-time feedback for spatiotemporal field stabilization in MR systems. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 73, 884–893 (2015).

3. M. Zaitsev, Julian. Maclaren, M. Herbst, Motion Artefacts in MRI: a Complex Problem with Many Partial Solutions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 42, 887–901 (2015).

4. S. Gross, C. Barmet, B. E. Dietrich, D. O. Brunner, T. Schmid, K. P. Pruessmann, Dynamic nuclear magnetic resonance field sensing with part-per-trillion resolution. Nat Commun. 7, 13702 (2016).

5. K. M. Gilbert, P. I. Dubovan, J. S. Gati, R. S. Menon, C. A. Baron, Integration of an RF coil and commercial field camera for ultrahigh‐field MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Med. 87, 2551–2565 (2022).

Figures