5275

Using Convolutional Neural Networks to detect and remove out-of-voxel MRS artefacts

Aaron T Gudmundson1,2, Kathleen E Hupfeld2,3, Yulu Song2,4, Helge J Zöllner1,2, Christopher W. Davies- Jenkins1,2, İpek Özdemir1,2, Georg Oeltzschner2,3, and Richard A E Edden1,2

1The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological SciencesRadiology and Radiological Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 4The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

1The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological SciencesRadiology and Radiological Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 4The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Spectroscopy, Out-of-voxel (OOV), MRS, Artefacts, Deep Learning, Convolutional Neural Network

Out-of-voxel (OOV) artefacts, or echoes, are common in-vivo artefacts seen in MRS data. These artefacts are typically not identified until post-processing and are challenging to remove without modifying the underlying data. Here, we developed 2 Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to overcome OOV artefacts at different stages. The first network (CNN1) was designed to identify OOV artefacts in single average data and offer a real-time assessment during data acquisition. The second (CNN2) predicts the OOV artefact to subtract during post-processing without impacting the metabolite data.Introduction

Out-of-voxel (OOV) echoes are a common in vivo artefact seen in MR spectra, which appear as broad signals with a ‘squiggly’ appearance1. These artefacts can mask signals of interest and cannot be accommodated by current modeling approaches for metabolite quantification. OOVs arise from gradient echoes; that is, signals from outside the shimmed voxel of interest are refocused by evolution in local field gradients that are either inherent (from air-tissue-bone interfaces) or arise from second-order shim terms2. Therefore, brain regions close to air cavities (e.g. medial prefrontal cortex) or which require stronger shim gradients (e.g. thalamus, hippocampus) most commonly exhibit OOV artefacts2 and can limit the utility of MRS in these disease-relevant regions3. Changing slice order, optimizing gradient schemes, or knowing where OOV signals originate can mitigate these artefacts to some extent3-6. Deep learning provides a promising approach but must be carefully implemented so as not to modify the target data7. In this work, two Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) were developed: the first network (CNN1), to detect OOV echoes (ultimately, to make real-time adjustments to acquisition protocols); and the second (CNN2), to predict the OOV echo for subtraction from the data.Methods

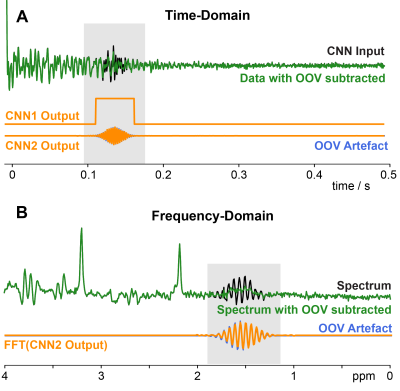

186,600 (180,000 training, 1,800 validation, 4,800 testing) synthetic spectra were simulated with in vivo-plausible combinations of metabolite, macromolecule, residual water signals, and noise in order to train and evaluate the CNN. Complex Gaussian OOV signals were modeled in the time domain with 4 parameters: center timepoint, frequency, width, and amplitude, and then added to 85% of the synthetic spectra. An example of the time-domain input and corresponding frequency-domain spectrum for visualization can be seen in Figure 1. Both CNNs used a U-net architecture with the input and output layers receiving and returning complex time-domain data of the same size (2048 points). The OOV detection network CNN1 was trained to return a binary vector with a value of 1 within the time range of OOV echoes (defined for training purposes as the 5% Gaussian cut-off), and zero otherwise. The OOV prediction network CNN2 was trained to return the OOV echo, or a zero vector where there was no OOV echo.Results

CNN1 had a 98% discovery rate in identifying OOV echoes, and a 4% false discovery rate, and localized the echo center-point within 0.5 ms for unseen testing data. CNN2 successfully predicted the OOV signal with a high level of fidelity – subtracting the predicted OOV signal reduced OOV echo amplitude by 89% (78%-93%; Q1-Q3).Discussion

OOV echoes have become a particular recent concern because: 1. New studies increasingly focus on challenging brain regions; 2. Use of multi-metabolite editing increases the likelihood of exciting OOVs; 3. Detection of low-concentration metabolites reduces the maximum size of OOV that can be tolerated; 4. Recent consensus analysis methods do not apply exponential line-broadening filters, which reduce the amplitude of OOV signals. The approach that we are taking is to combat OOV artefacts at two stages: acquisition and processing. Since collecting artefact-free data is the ideal, we have developed CNN1 to ultimately be integrated into the scanner sequence and trigger automatic adjustments to improve data quality during acquisition. As some artefacts may persist even after adjustments, we have also developed CNN2 to remove artefacts in post-processing. By predicting the echo and subtracting it, rather than predicting the echo-free data, we reduce the chances of modifying the underlying metabolite data. Overall, CNN1 was highly successful in detecting OOVs in synthetic MRS data. Preliminary testing suggests that the network is also successful in detecting in vivo OOV artefacts in single averages (including detecting multiple OOV signals in a single FID). CNN2 was able to predict the OOV signal directly while having negligible impact on the underlying data. Together, these findings clearly demonstrate the potential for CNNs to identify and reduce OOVs in in vivo MRS.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 NS123115, R01 EB016089, R01 EB023963, R21 AG060245, R00 AG062230, K00 AG068440, P41 EB031771.References

- Kreis R. Issues of spectral quality in clinical 1H‐magnetic resonance spectroscopy and a gallery of artifacts. NMR in Biomedicine 2004;17(6):361-381.

- Starck G, et al. K‐space analysis of point‐resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) with regard to spurious echoes in in vivo 1H MRS. NMR in Biomedicine 2006;22(2):137-147.

- Ernst T, & Chang, L. Elimination of artifacts in short echo time 1H MR spectroscopy of the frontal lobe. MRM 1996, 36(3), 462-468.

- Carlsson Å., et al. Degraded water suppression in small volume 1H MRS due to localised shimming. MAGMA 2011;24(2):97-107.

- Berrington, A, et al. (2021). Estimation and removal of spurious echo artifacts in single‐voxel MRS using sensitivity encoding. MRM 2021; 86(5):2339-2352.

- Song Y, et al. Impact of gradient scheme and shimming on out-of-voxel echo artifacts in edited MRS. NMR in Biomedicine 2022; e4839.

- Kyathanahally, SP, et al. Deep learning approaches for detection and removal of ghosting artifacts in MR spectroscopy. MRM 2018; 80(3):851-863.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5275