5265

Optimizing a Clinically Feasible 31P Liver MRSI Protocol at 3T1School of Health Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States, 2Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Liver, Fatty Liver Disease

Optimizing a clinically feasible 31P liver MRSI protocol on a 3T SIEMENS system through the lens of a diffuse fatty liver disease study. Protocol practicality is driven primarily by scan length, patient comfort, and data quality. Voluntary scanning subjects, ranging from healthy to overweight, are sourced from the university population. Both a dual-tuned, 8-channel 1H/31P phased array coil (wrapped around the whole torso) and an 11-cm-diameter flexible surface coil are available for use. Techniques, testing results, and relative advantages of either are discussed in detail, as well as the implications for each choice in a clinical setting.

Introduction

Numerous studies have demonstrated the potential of Phosphorus-31 (31P) MRS in assessing chronic fatty liver disease1-3. However, typical hepatology clinics serve significantly overweight patient populations and often lack access to large, multi-channel Tx/Rx volume coils that can effectively probe deeper regions. While 10-15 cm 31P surface coils (commonly used for muscle metabolism experiments) may not be the definitive choice for liver measurements4, careful protocol optimization can enable sufficient data quality even when faced with above average body-mass-indices (BMIs). This abstract reviews the general optimization process for a 31P liver MRSI protocol, drawing specifically from experiences with two coils on a 3T Siemens Prisma system.Project Goals

This research was aimed at studying a combination of 1H and 31P MRS metabolite signals as non-invasive biomarkers for diffuse liver disease prognosis. Although resources and definitions will inevitably vary between projects, this particular study regarded "clinically feasible" as requiring strictly less than 60 minutes of scanner room time, causing minimal patient discomfort, and acquiring highly reproducible results. Taking subject setup, imaging, shimming, and 1H MRS time into account allowed roughly 30 minutes for the 31P MRSI acquisition.Previously our group acquired 31P MRSI liver data with a custom, 8-channel dual-tuned 1H/31P phased array coil5. Thus, one side of optimization built off the old protocol, testing thoroughly for performance differences or changes compared to older data. Conversely, a recently obtained dual-tuned 1H/31P flexible surface coil (RAPID MR International), originally optimized for leg muscle, also had potential for liver application; the second approach made use of this newer, slimmer coil.

Methods

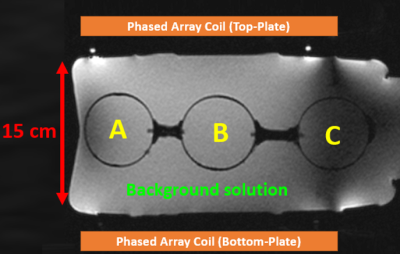

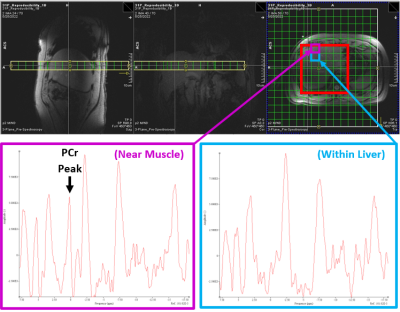

All protocol testing occurred on a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner at the Purdue MRI Facility. A signal localization phantom was constructed using a 10-L carboy with spherical compartments and various solutions of 31P metabolites (Figure 1) for initial testing and periodic coil QA. Most in vivo optimization utilized healthy university volunteers, with more overweight subjects (28+ BMI) in latter stages of testing.Since focal liver lesions were not of direct interest, but diffuse disease status, an SVS method (ISIS6) could have sufficed. However, testing demonstrated superior results from a weighted 2D CSI FID (TE = 2.3 ms) sequence. In addition to providing higher resolution, an MRSI approach also allowed differentiation of muscle and liver voxels based on phosphocreatine (PCr) signal (see Fig. 2). With this decision made, work focused on finding the ideal patient setup, shimming process, and parameters (TR, FOV, matrix size, coupling) for the clinical study.

Each parameter test involved uninterrupted scanning of a subject while altering one parameter (e.g. TR = 1000 ms vs. 2000 ms). In addition to 3D localizer planning, axial “pre-CSI” and “post-CSI” anatomical imaging was employed to detect any subject shifts during scanning. Operators made extensive use of the “manual adjustments” tab (VE11C) to minimize spectral linewidth. Data was exported in DICOM, RDA, and “raw” (TWIX) formats, then analyzed using jMRUI.

Parameters and Coil Comparison

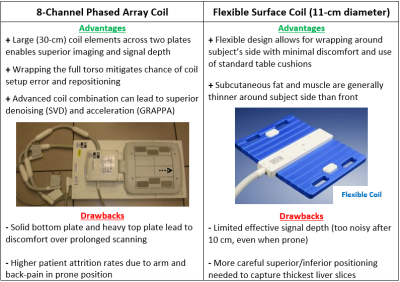

Phantom and in vivo testing supported the following MRSI parameters: FOV = 400 mm, slice thickness = 30 mm, matrix size = 16x16, spectral bandwidth = 5.0 kHz, flip angle = 90°, TR = 1000 ms, and no decoupling with 36 weighted averages (29:20 TA). While smaller FOVs can certainly capture the entire liver (Figure 2), data backed 400 mm FOV with 25 mm resolution as an ideal compromise of coverage, signal, and resolution. For bandwidth, anything above 2.0 kHz is more than adequate for capturing the relevant ~30 ppm range of 31P metabolites. Although proton decoupling offered a slight improvement to peak quality, it also introduced significant SAR limitations to flip angle and TR. Optimum shimming results were obtained by positioning the adjust volume entirely within the liver (Figure 2) and measuring, calculating, and applying a 3D “GRE Abdomen” field map twice. The best reference voltage was determined by incrementing from 30 V to 150 V in the “X Frequency” tab and recording each “Max signal” value, choosing a final voltage within the peak of the derived curve.Advantages and disadvantages of both the 8-channel phased array and flexible surface coils are outlined in Figure 3. Even though the former offers greater deep tissue signals, nearly all healthy volunteers reported significant discomfort with the 8-channel phased array. This often necessitated extra padding on the coil’s bottom plate, diminishing its effective signal depth; some subjects even refused future rescans, an opinion also shared among past hepatocellular cancer patients. In contrast, the flexible surface coil did not require removal of the standard table cushions and was the clear favorite among volunteers that experienced both. Figure 4 illustrates prone and supine coil setups with results.

Protocol and Future Plans

With these observations in mind, the flexible surface coil was deemed the superior choice for this clinical fatty liver disease study. Ideally, willing patients will be scanned head-first and prone to minimize breathing motion. If deemed unable, they can instead be scanned supine with the coil securely fastened in place. Future work is focused on developing an apparatus to reliably restrict breathing motion, as well as the application of novel accelerated sequences to reduce overall scan time.Acknowledgements

Data acquisition was supported in part by the Indiana CTS, funded in part by UL1TR001108. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Anshuman Panda (for his initial work with the 8-channel coil) and Dr. Jens Rosenberg (University of Florida) for his advice on SIEMENS X-nuclei sequence calibration.References

1Meyerhoff DJ, Karczmar GS, Matson GB, Boska MD, Weiner MW. Non-invasive quantitation of human liver metabolites using image-guided 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 1990;3(1):17-22.

2Jeon MJ, Lee Y, Ahn S, et al. High resolution in vivo 31P-MRS of the liver: potential advantages in the assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Radiol. 2015;56(9):1051-1060.

3Valkovic L, Chmelik M, and Krssak M. In-vivo 31P-MRS of skeletal muscle and liver: A way for non-invasive assessment of their metabolism. Anal Biochem. 2017;529:193-215.

4Chmelik M, Schmid AI, Gruber S, et al. Three-dimensional high-resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging for absolute quantification of 31P metabolites in human liver. Magn Reson Med. 2008;(4):796-802.

5Panda A, Jones S, Stark H, et al. Phosphorus liver MRSI at 3 T using a novel dual-tuned eight-channel 31P/1H H coil. Mag Reson Med. 2012;68(5):1346-1356.

6Ordidge RJ, Connelly A, and Lohman JAB. Image-selected in Vivo spectroscopy (ISIS). A new technique for spatially selective nmr spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1986;66(2):283-294.

Figures

Figure 1: 31P Signal Localization Phantom for Initial Testing and Coil QA.

Localization phantom constructed from a 10-L carboy (36x21x15 cm3) and filled with a background solution of 15 mM potassium phosphate monobasic (Pi peak ~5 ppm), 75 mm NaCl, and 0.04 g/L NiCl2. Sphere A contained 100 mM MPA (resonance ~34 ppm), Sphere B 100 mM PPA (~21 ppm), and Sphere C a mixture of 100 mM MPA and 50 mM Pi. The large phantom modeled a subject torso or abdomen, estimating the signal depth capabilities of either coil. Water-filled fiducial markers (bright white) on the top plate outline coil boundaries.

Figure 2: Typical CSI Grid and Adjust Volume Setup

2D CSI grid setup with FOV = 400 mm. Adjustment volume is highlighted red in the axial plane. Spectra have been phased-corrected within jMRUI and displayed with a 15 Hz Lorentzian filter. In this subject (BMI = 30 kg/m2) there are three full voxel rows (7.5 cm) of fat and muscle tissue before “true” liver signal with a lack of PCr peak. Since the anterior voxel borders muscle, it invites a significant amount of PCr contamination from the weighted point spread function

Figure 4: Prone vs. Supine Coil Setup and Results

Images of flexible surface coil placement and selected jMRUI voxels (15 Hz filter) from a subject (BMI = 30 kg/m2) scanned twice on the same day with prone and supine positioning. For head-first prone subjects, both arms remain above the head throughout scanning. For head-first supine, both arms remain at the subject's side. Signal rapidly falls off once exceeding 3-4 voxels (7.5-10 cm) of depth in the body. As expected, prone positioning visibly reduces breathing motion, improving spectral quality at the slight cost of subject comfort.