5257

Navigator-Based In-Plane Motion Correction for High Resolution 2D T2-Weighted Spin-Echo Prostate MRI

Eric A. Borisch1, Adam T Froemming1, Roger C. Grimm1, Daniel Reiter2, Phillip J. Rossman1, and Stephen J. Riederer1

1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2St. Olaf College, Northfield, MN, United States

1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2St. Olaf College, Northfield, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Motion Correction

The addition of ky≈0 navigator views to detect anterior-posterior prostate (peristalsis-induced) motion to the end of each echo train for a 2D T2-weighted acquisition stack with slice-profile recovery reconstruction is investigated. ROVir virtual coils are used to focus the spatial sensitivity in the phase direction of the navigator response on the small, central prostate region. Mutual information is used to register these navigators across the acquisition, with the resulting movement time course used to correct the acquired data. Results both in motion controlled phantom and human studies are discussed.Introduction

T2-weighted 2D multi-slice spin-echo (T2SE) acquisition is central to prostate MRI1. With PI-RADS recommendations for in-plane resolution to be well under 1mm, motion due to peristalsis can be a limitation. Although antispasmodics can be effective, there is no consensus on their usage1, and motion may still occur2. Methods such as PROPELLER3 can be used for motion correction but at a cost of 50% increased scan time. It has been noted previously that displacement of the prostate due to peristalsis is primarily in the A/P direction4,5. Thus, the purpose of this work was to develop a means for detecting subtle (<2mm) A/P motion of the prostate during a T2SE acquisition. To sensitize motion detection to the relatively small prostate deep within the stationary tissues of the pelvis, the region-optimized virtual coils (ROVir6) technique was also employed.Methods

To avoid slice-to-slice interference, T2SE acquisition of abutting slices is typically done in multiple passes; e.g. odd-numbered slices in one pass, even-numbered in a second. The starting point in this work was a four-pass acquisition which provided overlapping slices, devised to allow improved slice resolution using slice profile correction7. For the typical acquisition parameters used: TR (3000-4000 msec), phase resolution (280 samples over 20 cm), acceleration factor (1.5), and echo train length (21), the data for each slice is collected over 16-20 repetitions. Specific to this project, at the end of each echo train we added two low-pass (k-space phase encodings closest to ky=0) 1-D navigator “NAV” echoes. While these are effectively averages of intensity along the entire phase encode direction (here L/R), they retain high (0.6mm) resolution in the frequency encode (A/P) direction. Addition of these NAVs slightly increased the TR time.The reference acquisition uses 30-35 coil elements, with roughly half positioned in-table posterior to the patient and half configured in an anterior blanket coil array. The ROVir method requires definition of target and interference regions. An oval target region of approximately 8cm diameter was defined centrally, encompassing the region of the prostate. The interference region was defined laterally to this, devised to account for the lack of spatial selectivity along the phase direction for the near-ky=0 NAV echoes. After acquisition and ROVir processing the targeted NAV echoes for each slice were aligned via a mutual-information metric, resulting in a measure of the time course of shifts in the frequency (A/P) direction. The temporally-matched k-space views for each NAV were then corrected via phase ramps, and these adjusted views were then used as input for the conventional (non-ROVir) reconstruction process.

The new method was tested using a phantom and in humans, the latter done under an IRB-approved protocol requiring written consent. The phantom was comprised of a central 6cm wide narrow region containing an egg-sized prostate inclusion, surrounded by two 16cm wide, stationary, laterally-placed signal-generating regions. Motion of the narrow central region was controlled by a programmable stepper motor.

Results

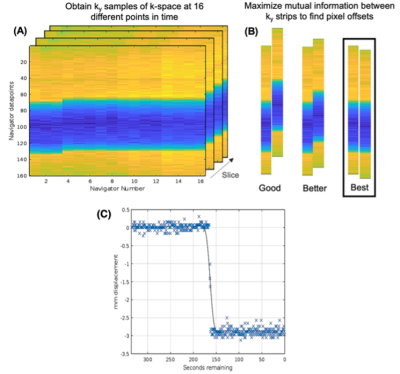

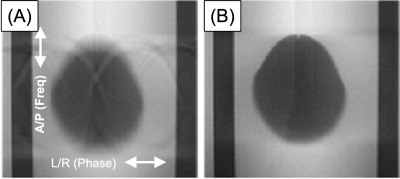

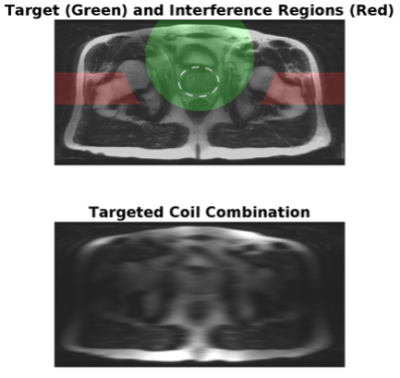

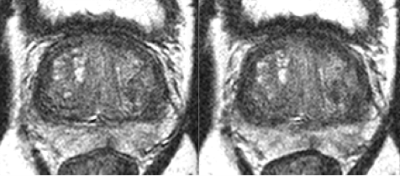

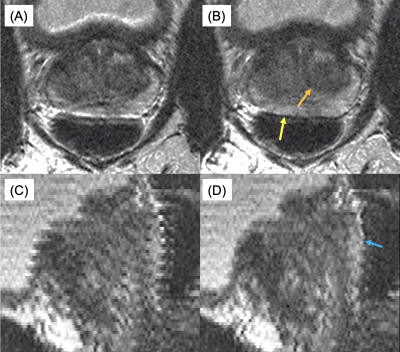

An example of navigator results over time and detected motion for a given slice from a phantom study are shown in Figure 1. For the phantom study all slices are subject to the same motion, and data points for all slices are shown in Figure 1C. Gaussian smoothing of the samples (black curve) closely follows the prescribed, abrupt 3mm movement. Similar results were obtained for other; e.g. gradual linear, motion. Figure 2 shows zoomed images of the central region and the dark, prostate-mimicking inclusion without (A) and after (B) correction for motion. An axial image containing the prostate (within the dashed white line) and showing the ROVir target (green) and interference (red) regions is shown in Figure 3. Axial images from one subject without and with correction are shown in Figure 4, demonstrating improved sharpness. Axial and sagittal images for second subject are shown in Figure 5, showing improved sharpness and better slice-to-slice registration.Discussion

This work provides initial results using near-ky=0 navigator echoes combined with ROVir, leveraging multi-coil data to weight the otherwise spatially insensitive in phase navigator data, to perform both intra- and inter-slice motion detection and correction in the context of slice-resolution-recovering reconstruction T2SE imaging of the prostate. Such acquisitions can be especially sensitive to motion. As seen in Figure 1C, with the use of the mutual information metric, the level of accuracy and precision (≈0.2mm) is well under the frequency encoding resolution (0.6mm). Addition of the NAV echoes to the echo train slightly increases the total readout duration per slice, resulting in a slight (<10%) increase in TR.Conclusion

The ability to detect and correct prostate motion from central phase-encode navigators with ROVir-based spatial suppression has been demonstrated, with the navigators adding less than 10% to the total scan time. The process for selecting ROVir masks and the optimal number of resulting coils to use remains an area for optimization. Alternative approaches leveraging the bulk of each echo train (in addition to the consistently acquired navigators) for motion detection, or preferentially applying correction by utilizing ROVir virtual coils during the reconstruction itself are potential future enhancements.Acknowledgements

References

- Turkbey B, et al. Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2.1: 2019 Update of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2. Eur Urol. 2019 Sep;76(3):340-351.

- Ullrich T, et al. Hyoscine butylbromide significantly decreases motion artefacts and allows better delineation of anatomic structures in mp-MRI of the prostate. Eur Radiol. 2018 Jan;28(1):17-23.

- Pipe JG. Motion correction with PROPELLER MRI: application to head motion and free-breathing cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999 Nov;42(5):963-9.

- Padhani AR, et al. Evaluating the effect of rectal distension and rectal movement on prostate gland position using cine MRI. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999 Jun 1;44(3):525-33.

- Borisch EA, et al. Cross correlation-based misregistration correction for super resolution T2 -weighted spin-echo images: application to prostate. Magn Reson Med. 2021 Mar;85(3):1350-1363.

- Kim D, et al. Region-optimized virtual (ROVir) coils: Localization and/or suppression of spatial regions using sensor-domain beamforming. Magn Reson Med. 2021 Jul;86(1):197-212.

- Kargar S, et al. Use of kZ -space for high through-plane resolution in multislice MRI: Application to prostate. Magn Reson Med. 2019 Jun;81(6):3691-3704.

Figures

Figure 1: 1-D Navigator response over time in a phantom study. A clear shift is visible (A) due to applied movement between (temporally ordered) navigators 3 and 4. A mutual information metric is used to spatially align the navigators across time, as visualized in (B). Detected movement (C) from a phantom study (separate series from A,B) with a motion-controlled 3mm shift.

Figure 2: Example of prostate inclusion in motion-controlled phantom as acquired (A) and with motion correction based on the described technique (B). Blur of lower edge due to partial volume effect with tilted egg-shaped inclusion.

Figure 3: Combination of all coil responses as received (top) showing the target (green) and interference (red) regions, and with ROVir targeting (visualized with fully-sampled central region only, bottom)

Figure 4: Example of improved result in the prostate (right) from KZM reconstruction with motion correction.

Figure 5: Uncorrected (A,C) and motion-corrected (B,D) axial images and sagittal reformats of the prostate. In (B) note the improved definition of the posterior prostate capsule (yellow arrow) and improved sharpness of the nodule (orange arrow). Note in (D) the improved consistency of the interface between the prostate and rectum (cyan arrow).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5257