5240

Rapid Luminescence Quantification of a Sensitized Gadolinium Based Contrast Agent1Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Radiology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Contrast Agent, Preclinical, Gadolinium Based Contrast Agent, Luminescence Quantification, Plasma Clearance Kinetics

Gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCA) are widely used in magnetic resonance imaging and are paramount to cancer diagnostics. Furthermore, accurate quantification of gadolinium in blood/plasma (clinical media) is essential to tumor pharmacokinetic analysis, with current methods being low throughput and clinically unavailable. As such, we have developed a simple luminescence quantification assay to measure the concentration of gadolinium in clinical media using a sensitized GBCA referred to as Gd[DTPA-cs124]. Here, we demonstrate the efficacy, increased relaxivity and enhanced biocompatibility of our agent when compared to other GBCA’s, as well as its ability to model pharmacokinetic clearance in a mouse model.Introduction

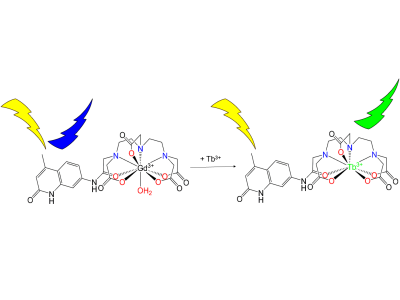

Gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCA) are widely used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and are especially important for early diagnoses of diseases such as cancer.1 The use of GBCA’s also extends to grading tumors or assessing tumor treatment response, by measuring contrast delivery to and from tumors.2, 3 However, accurate measurement of GBCA’s in tissue remains challenging due to uncertainties in multiple factors.3,4,5 A potential solution to this issue is to use a bimodal GBCA that can be quantified via MRI contrast enhancement as well as luminescence intensity. In the past a sensitized ligand known as DTPA-cs124 had been studied as an optical probe for detecting luminescent lanthanides outside the context of MRI.6 More recently, Russel et al. was able to demonstrate the use of this probe to detect gadolinium in mouse plasma with a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) assay using a luminescent probe (Tb[DTPA]) in the presence of Gd[DTPA-cs124].7 However, this method does not account for or explain the transmetallation occurring between these two metals in-situ. Alternatively, a controlled metal displacement assay between Gd[DTPA-cs124] and terbium can be utilized to transform an otherwise non-luminescent complex (Gd[DTPA-cs124]) into a long-lived, highly luminescent species (Tb[DTPA-cs124]), thereby offering luminescence quantification as a secondary method to measuring the concentration of gadolinium (Figure 1). Here we investigate the effectiveness of Gd[DTPA-cs124] as a bimodal MRI contrast agent that can be used to measure the concentration of gadolinium in blood and plasma via luminescence.Methods

The synthesis and purification of DTPA-cs124 and its chelates were performed using modified methods described by Russel et al.7Standard Curves: The luminescence assay was carried out at pH 7 by mixing known amounts of Gd[DTPA-cs124] along the concentration interval of 0.1 nM to 1 mM with an ICPMS standard solution of Tb(NO3)3 diluted to 1mM. Standard Curves were obtained for human blood (5%), human plasma (5%), mouse blood (5%), and aqueous buffer. All luminescence measurements were acquired in triplicate with excitation/emission at 330/545 nm, a 100 µs read delay and 1900 µs integration time using a Biotek H1MF plate reader.

Chelate Stability Measurements: All measurements were taken on a Bruker Minispec at 60 MHz following a modified protocol described by Laurent et al.8

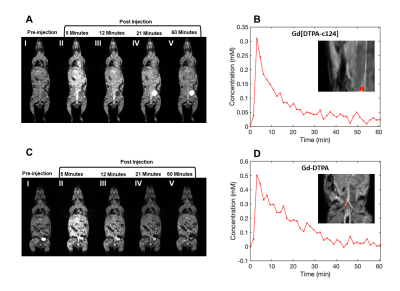

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: 4- to 6-week C57/BL6 mice were used for MRI experiments. To illustrate the in-vivo contrast enhancement and qualitative biodistribution of Gd[DTPA-cs124], a bolus of Gd[DTPA-cs124] was injected at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg via a tail vein (n = 3). The same imaging protocol was acquired in another animal serving as a reference with an injection of Gd[DTPA], at the same dose (n = 1).

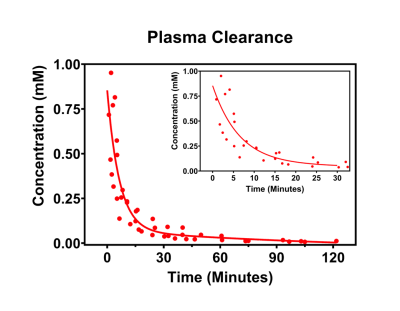

Transmetallation Assay to Measure Plasma Clearance: 4- to 6-week C57/BL6 mice (n = 5) were administered a bolus injection of Gd[DTPA-cs124] at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg via tail vein. Blood samples were obtained from each mouse at various time points post injection. Blood samples were prepared and measured following the assay method described above, and luminescence intensity measurements were plotted against a standard curve to infer the concentration of Gadolinium in each sample.

Results

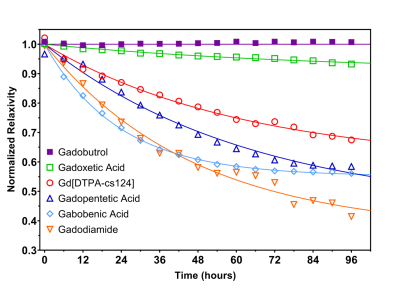

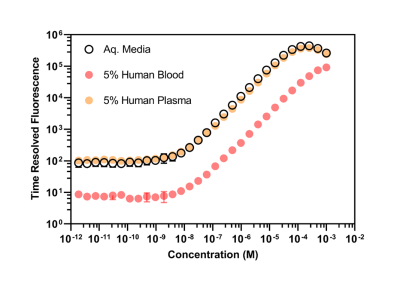

The r1 of Gd[DTPA-cs124] at 60 MHz was found to be 5.09 ± 0.02 s-1 mM-1 in aqueous buffer at 37.5 °C, and the stability index (SI) calculated as a normalized ratio from the competitive cation assay was 0.676 ± 0.015 (Figure 2). A strong linear correlation between relaxivity and molecular weight was established for all the contrast agents studied (R2 = 0.927, p = 0.987, Table 1). The limits of detection of Gd[DTPA-cs124] in each media were as follows: 0.46 nM for aqueous buffer, 0.43 nM for 5% human plasma, 3.02 nM for 5% human blood and 148.67 nM for 5% mouse blood (Figure 3). Using a Wilcoxon signed rank test, the limits of detection between aqueous buffer and human plasma were not significantly different (W = 252, p = 0.20). However, the limits of detection between aqueous buffer and human blood (W = 0, p < 0.001) as well as human plasma and human blood were (W = 0, p < 0.001). The fast and slow half-lives calculated from the plasma clearance measurements acquired using our quantification assay were 4.5, and 105.0 minutes respectively (Figure 5).Discussion/Conclusion

While the increase in relaxivity when comparing Gd[DTPA-cs124] to Gd[DTPA] is explained by the strong linear relationship between r1 and molecular weight, the increase in stability is most likely attributed to an increase in rigidity of the chelate (Figure 2).9 These findings imply that similar chemical modification to other clinically approved GBCA’s may enhance their relaxivity and biocompatibility, while providing them with the ability to serve as a bimodal tracer. Furthermore, our assay shows sensitivity to the nanomolar range, and is reflected by the limits of detection measured in aqueous buffer, human plasma, and human blood (Figure 3). Additionally, mice administered Gd[DTPA-c124] exhibited successful signal enhancement and in-vivo clearance when compared to reference images acquired using gadopentetic acid (Gd[DTPA]) (Figure 4). Finally, our assay provides half-lives that agree with previously reported GBCA clearance data in mice, measured using Gd-153 radiolabeled gadopentetic acid, where the fast clearance half-life was measured to be between 5-6 min (Figure 5).10Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSF-DMREF under Award Number DMR 1728858, NSF-MRSEC Program under Award Number DMR 1420073, the NYU Shiffrin-Myers Breast Cancer Discovery Fund, NIH/NCI R01CA160620, and the NYU CTSA grant UL1 TR000038 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The majority of this work was performed at the NYU Langone Health Preclinical Imaging Laboratory, a shared resource partially supported by the NIH/SIG 1S10OD018337-01, the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center Support Grant, NIH/NCI 5P30CA016087, and the NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center Grant NIH P41 EB017183. The authors would like to thank G&M, the members of the Radiochemistry lab at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, as well as the labs of Youssef Z. Wadghiri, Sungheon Gene Kim, Dan Turnbull, and Jiangyang Zhang for their continued support and feedback during the evolution of our work.

References

(1) Choyke PL, Dwyer AJ, Knopp MV. Functional tumor imaging with dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2003, 17 (5), 509-520. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.10304.

(2) Ramalho J, Semelka RC, Ramalho M, Nunes RH, AlObaidy M, Castillo M. Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agent Accumulation and Toxicity: An Update. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2016, 37 (7), 1192-1198. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A4615.

(3) Bharadwaj Das A, Tranos JA, Zhang J, Wadghiri YZ, Kim SG. Estimation of Contrast Agent Concentration in DCE-MRI Using 2 Flip Angles. Investigative Radiology 2022. DOI: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000845.

(4) Knowles BR, Batchelor PG, Parish V, Ginks M, Plein S, Razavi R, Schaeffter T. Pharmacokinetic modeling of delayed gadolinium enhancement in the myocardium. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2008, 60 (6), 1524-1530. DOI: 10.1002/mrm.21767.

(5) Harrigan CJ, Peters DC, Gibson CM, Maron BJ, Manning WJ, Maron MS, Appelbaum E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: quantification of late gadolinium enhancement with contrast-enhanced cardiovascular MR imaging. Radiology 2011, 258 (1), 128-133. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.10090526.

(6) Li M, Selvin PR. Amine-reactive forms of a luminescent diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid chelate of terbium and europium: attachment to DNA and energy transfer measurements. Bioconjugate Chemistry 1997, 8 (2), 127-132. DOI: 10.1021/bc960085m.

(7) Russell S, Casey R, Hoang DM, Little BW, Olmsted PD, Rumschitzki DS, Wadghiri YZ, Fisher EA. Quantification of the plasma clearance kinetics of a gadolinium-based contrast agent by photoinduced triplet harvesting. Analytical Chemistry 2012, 84 (19), 8106-8109. DOI: 10.1021/ac302136e.

(8) Laurent S, Vander Elst L, Henoumont C, Muller RN. How to measure the transmetallation of a gadolinium complex. Contrast Media & Molecular Imaging 2010, 5 (6), 305-308. DOI: 10.1002/cmmi.388.

(9) Clough TJ, Jiang L, Wong KL, Long NJ. Ligand design strategies to increase stability of gadolinium-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Nature Communications 2019, 10 (1), 1420. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-09342-3.

(10) Tweedle MF, Wedeking P, Kumar K. Biodistribution of Radiolabeled, Formulated Gadopentetate, Gadoteridol, Gadoterate, and Gadodiamide in Mice and Rats. Investigative Radiology 1995, 30 (6), 372-380. DOI: 10.1097/00004424-199506000-00008

Figures