5236

An open-source platform for simulating internal organ motion: Preliminary results

Eddy Solomon1 and Leeor Alon2

1Radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

1Radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Phantoms, Motion Correction

Motion-correction techniques require an objective quantitative assessment under controlled conditions. In this work, we present an open-source platform for simulating internal ‘organ’ motion under realistic scan conditions. The phantom was composed of two partitions which include a high-resolution inner compartment translated in space using a Lorentz force, within a larger body-like second compartment. The motion phantom was controlled using custom-made software and was tested with a radial MR sequence, demonstrating motion-resolved capabilities.KEYWORDS

motion-phantom, motion-correction, Lorentz Force, high-resolution phantomINTRODUCTION

Prospective and retrospective motion-correction methods have a long history with an array of solutions1. The effectiveness of these methods relies on many factors, including the physics, sampling trajectory, temporal-resolution, quality information provided by surrogate motion sensors, and more2. The verification of these techniques raises the need for objective quantitative assessment under controlled conditions. One possible solution is the development of a standardized motion platform that can simulate the physiology and that can be used for assessment of MR-specific applications. While MR-compatible motion phantoms are challenging to fabricate, they can provide an invaluable ground truth tool for validation, analysis, and quality control. Moreover, to mirror more accurately internal body organs, high-resolution features and motion-specific characteristics are needed. In this work, we describe a joint solution to the above by the development of an open-source motion-controlled phantom driven by a Lorentz Force mimicking internal ‘organ’ displacement. The phantom is composed of two partitions which include a high-resolution inner compartment translated in space within a larger body-like compartment. The motion phantom approach was tested with a radial MR sequence, demonstrating motion-resolved capabilities.METHODS

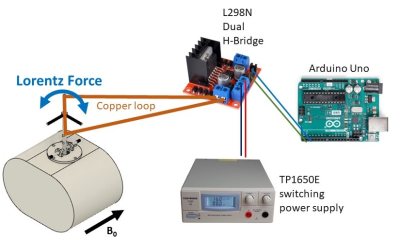

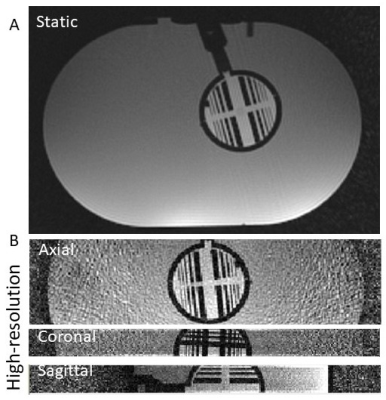

Phantom setup: The phantom was designed using the publicly available Fusion 360 software (Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA), composed of inner and outer compartments. The inner compartment included high-resolution features between 0.25mm and 4mm (Fig. 1A) that could be translated in space within a larger body-like volume (Fig 1B), which served as a second compartment. The phantom was printed using an HP Jet Fusion 580 3D printer (HP Inc., Palo Alto, CA) with nylon, resulting in water-tight 3D prints. Inner (Fig. 1A) and outer (Fig. 1B) compartments were filled with water and Gadovist such that they target the T1 values of muscle3 (0.1mM; 1400 ms) and pancreas4 (0.2mM; 850 ms) at 3T. Displacement of the inner compartment was achieved by introducing a current carrying copper wire attached to the vertical rod of the phantom, creating a Lorentz force on the rod, resulting in movement of the inner phantom in the x- and y-directions (Fig. 2). By changing the polarity of the current, the Lorentz force was reversed such that the inner phantom reverted its direction. An Arduino microcontroller was used to control the displacement using a custom-made script and an L298N dual H-bridge board was used to produce currents with different polarities (Fig 2). The H-Bridge and current carrying wire were connected in series to a TP1650E (Tekpower, Dongguan, China) power supply set at 4.6V and outputting 1.1 Amps. The motion phantom was tested during an 80 sec scan inside the magnet, while inner motion compartment (Fig 1A) was programmed to move every 10 to 12 seconds.Data acquisition: Images were acquired on a 3T Prisma system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a 16-channel spine matrix coil. The acquisition protocol included a radial stack-of-stars 3D GRE (RAVE) sequence with golden-angle scheme. RAVE imaging parameters included TR/TE=4.1/1.8ms, 20 slices, matrix size of 256x256, 1000 radial views and spatial resolution of 1.3x1.3x3.0 mm3. Since all spokes capture an equal distribution of k-space information, a Golden-angle RAdial Sparse Parallel MRI5 (GRASP) reconstruction was used, sorting and grouping the radial views into different frames, each representing a single motion state with 4.1 sec temporal resolution.

RESULTS

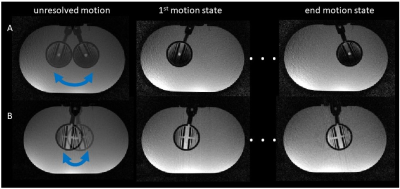

Inner and outer compartments, as illustrated in Figure 1, were imaged during a static (no motion) scan (Fig. 3A) and a dedicated high-resolution scan was acquired to illustrate the high-resolution features of the phantom across axial, coronal and sagittal planes (Fig. 3B). During a scan under motion conditions (Fig. 4, left), details are shown to be blurred thus obfuscating fine features of the structure. Motion-resolved reconstruction is shown in Figure 4 (middle and right), demonstrating ‘freezing’ of two motion states, at the beginning and end of the motion cycle. The extent of the motion was controlled and depicted in two different scenarios with large (Fig. 4A) and small (Fig. 4B) rotational angles.DISCUSSION

In this work, we present a highly customizable, open-source platform for simulating realistic motion that can be used for evaluation of image acquisition and reconstruction approaches in the presence of motion. While this approach utilizes displacement of the inner compartment in two directions, we are currently working on expanding the use of Lorentz forces for a more flexible 3D motion control, which will be pertinent for improved organ-like displacements. For improving repeatability and reproducibility, the project computer assisted design (CAD), schematics, and software can be found at: https://github.com/eddysolo/MR-Motion-Phantom-Platform.git.Acknowledgements

R21EB031336References

- Havsteen I, Ohlhues A, Madsen KH, Nybing JD, Christensen H, Christensen A. Are Movement Artifacts in Magnetic Resonance Imaging a Real Problem?-A Narrative Review. Front Neurol 2017;8:232. 2.

- Kober T, Gruetter R, Krueger G. Prospective and retrospective motion correction in diffusion magnetic resonance imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage. 2012 Jan 2;59(1):389-98. 3.

- Gold G, Han E, Stainsby J, Wright G, Brittain J, Beaulieu C. Musculoskeletal MRI at 3.0 T: relaxation times and image contrast. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004 Aug;183(2):343-51. 4.

- Tirkes T, Mitchell J, Li L, Zhao X, Lin C. Normal T1 relaxometry and extracellular volume of the pancreas in subjects with no pancreas disease: correlation with age and gender. Abdom Radiol 2019 Sep;44(9):3133-3138. 5.

- Feng L, Grimm R, Block KT, Chandarana H, Kim S, Xu J, Axel L, Sodickson DK, Otazo R. Golden-angle radial sparse parallel MRI: combination of compressed sensing, parallel imaging, and golden-angle radial sampling for fast and flexible dynamic volumetric MRI. Magn Reson Med 2014;72(3):707-717.

Figures

Figure 1: Motion phantom design. A 3D

print of the high-resolution phantom (A) placed inside a bigger, body-like,

compartment (B).

Figure 2. Motion control system. Phantom

was placed inside the magnet and was displaced using Lorentz force created by a

current-carrying copper wire placed inside the main magnetic field.

Figure 3. An axial view of the two

compartments (A). High resolution zoomed

view of the inner motion compartment across axial, coronal, and sagittal

projection (B).

Figure 4. 3D reconstruction of

unresolved and resolved motion states. Motion-resolved data was binned into two

different motion states, featuring large (A) and small (B) induced internal rotation

angles.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5236