5232

What should I use to fill my Ultra-high Field MRI phantom?

Felix Horger1,2,3, Jyoti Mangal1,2,3, Raphael Tomi-Tricot1,2,3,4, David Carmichael1,2,3, Joseph Hajnal1,2,3, and Shaihan Malik1,2,3

1Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3London Collaborative Ultra high field System (LoCUS), London, United Kingdom, 4MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Limited, Frimley, United Kingdom

1Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3London Collaborative Ultra high field System (LoCUS), London, United Kingdom, 4MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Limited, Frimley, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: High-Field MRI, Phantoms

We explored commonly used substances for phantoms, air, water, oil and Perfluoropolyether, for their suitability for imaging at ultra-high field (7T). We illustrate the impact of susceptibility matching and how to prevent transmit field doming by selecting a substance with low dielectric constant. This work provides insights into the variety and expected magnitude of effects and can serve as guidance when designing a phantom for a specific application.Introduction

Physical phantoms are a key tool for quality assurance, sequence development, and validation of quantitative MRI. Phantoms can be anything from water bottles to more sophisticated arrays of vials filled with different substances. Within the community there is a move toward standardisation for some applications, for example on the ISMRM-NIST phantom for quantitative MRI [1]. Although there are many possible designs for phantoms used for different specific purposes, a common design consists of samples with varying relaxation times embedded within a larger fluid-filled vessel. The latter is required for susceptibility matching to avoid large B0 variation in the samples. This is particularly important at ultra-high fields (UHF) where B0 distortion at interfaces between substances leads to significant signal loss with gradient echo sequences. Another problem at UHF is transmit field (B1+) inhomogeneity, leading to wide spatial variability in flip angles, and hence image contrast. A major issue is that water, which is commonly used for filling phantoms, also has a high dielectric constant (~80 [2]) which leads to severe B1+ inhomogeneity. In this abstract, the UHF-suitability of several commonly employed substances for filling phantoms is tested.Methods

A cylindrical phantom (MultiSample 120, Gold Standard Phantoms, UK) consisting of a circular array holding eight 15ml vials was used. The vials were filled with water doped with Manganese-Chloride in different concentrations {0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.5} mM.Five experiments were performed in which different media were used to fill the phantom’s body: (a) store-bought rapeseed oil, (b) mineral oil (Johnson’s Babyoil), (c) Doped water (1.5L 0.5mM Gad + 3.75g NaCl and 1kg sucrose [3]) recommended for matching tissue characteristics at UHF, air (i.e. empty), and Perfluoropolyether (PFPE; ‘Galden DET’, Performance fluids, UK). The PFPE formulation used had density 1.7g/cc and $$$\epsilon=2.1$$$ according to the data sheet.

For each filling-substance, high-bandwidth (1kHz/Px) T2*-weighted scans were acquired to investigate B0 inhomogeneities at media interfaces. For supporting this qualitative scan, B0 maps were also acquired using a multi-echo-time gradient echo sequence. Chemical shift was examined with a standard low bandwidth (250Hz/pixel) and higher resolution scan. A high-bandwidth (1kHz/pixel) multi-spin-echo scan was performed to show contrast changes due to B1+. Finally, quantitative B1+ maps were acquired with Actual Flip Angle Imaging (AFI) [4] (nominal flip angles $$$20^\circ$$$ for case (c) and $$$50^\circ$$$ for other cases).

Scans were performed on a 7T scanner (London Collaborative Ultra high field system, MAGNETOM Terra, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a Nova 8-TX 32-RX head coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA, USA).

Results & Discussion

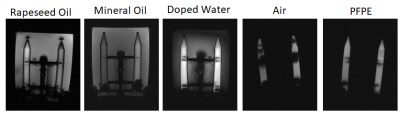

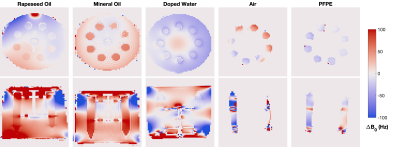

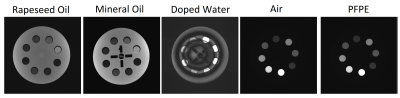

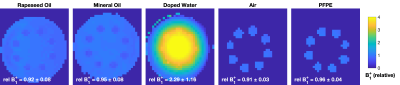

Fig. 1 shows T2* weighted scans. Signal loss at the ends of the tubes is worst in air; it also appears that the phantom’s fibre-glass structure holding the tubes has a non-negligible susceptibility offset, and affects the signal in the tubes regardless of the substance. Again this is most severe in air. B0 maps of the phantoms (Fig. 2) are not perfectly uniform in any phantom, owing to the difficulty of shimming the cylindrical shaped phantom particularly when filled with oil, which has a resonance frequency offset from water (present in the sample tubes). However, focusing on the degree of inhomogeneity of B0 within the sample tubes themselves, air gives by far the worst result – as expected.Hence a susceptibility matching medium is needed, however the B1+ maps (Fig. 5) and spin echo images (Fig. 4) show that water (which has relatively high $$$\epsilon$$$) causes severe B1+ inhomogeneity which can cause dramatic image artefacts and could severely confound quantitative imaging. Despite the doping added to the water, optimised to suppress doming, it failed to improve image quality significantly in our experience (data not shown).

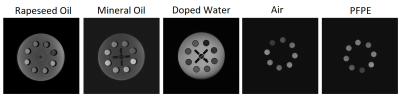

Hence, a low $$$\epsilon$$$ material is beneficial. Both the susceptibility and the permittivity conditions are fulfilled by oil; Fig. 5 shows very uniform B1+ for mineral and vegetable oil. However, oil may introduce chemical shift artifacts (Fig. 3), depending on the bandwidth, and might limit the choice of readout direction. The large chemical shift also complicates B0 shimming and choice of centre frequency, which can result in sub-optimal RF pulse settings for the water in the sample tubes.

PFPE has similar properties to the oils, but has no protons to generate an MRI signal. Thus, it will not produce chemical shift artefacts. The low dielectric constant of PFPE provided a significant advantage over other high $$$\epsilon$$$ PFPE materials causing less distortions in the RF field. Of all the materials tested, PFPE led to the most optimal conditions inside the sample tubes.

Potential drawbacks of PFPE are its relatively high expense, and also the lack of any background signal in the phantom; this could be an advantage or disadvantage depending on the application. Another potential issue with all non-conductive filling materials is that they do not load the RF coils in the same way as a human body which may lead to suboptimal performance.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we highlighted desirable as well as unfavourable properties of several commonly used substances in MRI for use in phantoms at UHF. The optimal choice depends on the exact scenario, and this abstract is to be seen as an illustration of the expected magnitude of possible effects.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT203148/Z/16/Z] and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London and/or the NIHR Clinical Research Facility. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.References

[1] KF Stupic et al. A standard system phantom for magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2021, DOI:10.1002/mrm.28779

[2] CG Malmberg et al, Dieletric Constant of Water from 0-100 degree C, Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, Vol. 56, No. 1, 1956.

[3] Q. Duan et al, Characterization of a dielectric phantom for high-field magnetic resonance imaging applications. Med Phys. 2014, DOI: 10.1118/1.4895823

[4] Yarnykh VL. Actual flip-angle imaging in the pulsed steady state: a method for rapid three-dimensional mapping of the transmitted radiofrequency field. Magn Reson Med. 2007 Jan;57(1):192–200.

Figures

Figure 1: T2* weighted scans demonstrating the need for susceptibility matching. Notice the signal loss at the tubes’ ends and at the middle of each tube where there appears to be a susceptibility mismatch caused by the phantom; signal loss is much worse in air than with any of the susceptibility matching fluids.

Figure 2: B0 maps reconstructed from multi-echo-time gradient echo scan. The B0 map for the air filled phantom shows strong inhomogeneity. Inhomogeneities observed in the others are due to difficult shimming (water-oil) and magnetic susceptibility of the phantom structure itself. Note that the different B0 in tubes of both oil phantoms is a reconstruction artefact (maximum frequency range +-100Hz, but water-oil shift is 1kHz), and in reality it is homogeneous.

Figure 3: Low bandwidth gradient echo scans demonstrating chemical shift artefacts.

Figure 4:

Multi-spin-echo scans for showing contrast changes due to

B1+ inhomogeneities for water, but not for other substances with low permittivity.

Figure 5: Relative B1+ maps acquired with an AFI scan. Mean and

standard error within the masked area are shown in each corner. All

substances apart from doped water give homogeneous B1+ close to the nominal value.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5232