5222

Design and Production of a 3D Printed Anthropomorphic Head Phantom for MRI – The Story so Far

George Michael John Bruce1,2, Pauline Hall-Barrientos1,2, and David Brennan1,2

1MRI Physics, Department of Clinical Physics and Bioengineering, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom, 2School of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

1MRI Physics, Department of Clinical Physics and Bioengineering, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom, 2School of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Phantoms, Phantoms, 3D Printing

Commercial phantom objects for use in MR can be expensive and poorly representative of human anatomy. 3D printing provides the potential to produce cheaper, novel and reproducible phantoms . This project investigates the potential use of 3D printed materials in the construction of an anthropomorphic head phantom for MRI. It can be effectively split into two different, smaller projects: investigation into MR properties of 3D printed materials and design of an anthropomorphic head phantom for MRI.Introduction

Quality assurance (QA) is performed on MRI scanners at their acceptance, significant upgrade, or periodically throughout the scanner’s lifetime. It is therefore of the utmost importance to use a reliable phantom object which remains consistent through time and is capable of testing various aspects of the system, such as SNR, geometric distortion, resolution and intra scanner variability. Currently, the majority of MR Phantoms do not mimic human anatomy and as such are not optimal for use in a scanner, which is designed to correct for the distortions and artefacts introduced by human anatomy. While 3D printing technology is rapidly evolving, there has been little work done on the use of MRI visible materials. Work done by He et al 20191 suggests that this manufacturing method affords the possibility of creating an anthropomorphic phantom for MRI, with a design which can be used to reproduce an identical phantom anywhere. This is supported by work done by Talawala and Beer et al (2020)2, where a selection of materials from the Poro-Lay series of filaments were found to have T1 properties relatively close to that of grey (LAYFOMM 40) and white matter (LAY-Felt). These materials are made up of a combination of a thermoplastic polyurethane and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA).Methods

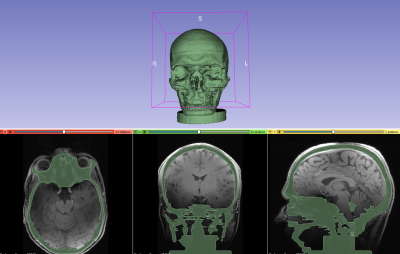

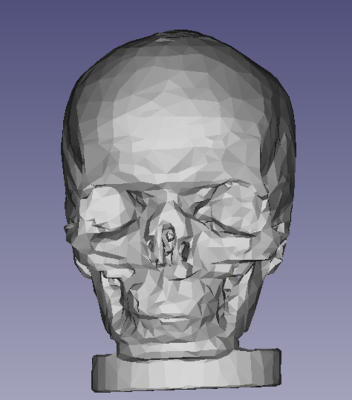

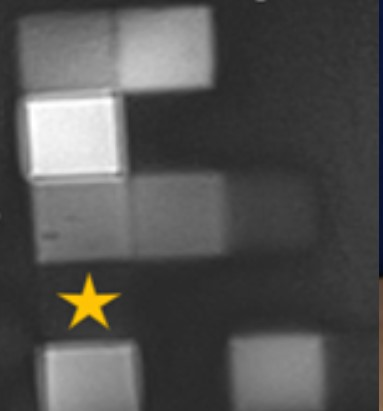

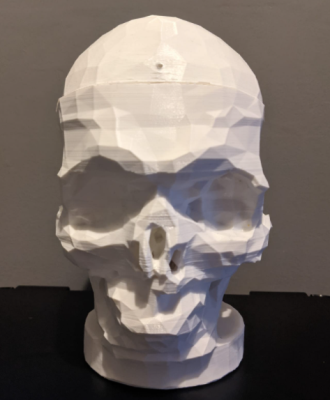

Over 25 different 2cm x 2cm x 2cm blocks of 3D printed materials were tested to evaluate their T1 and T2 and to assess their suitability for use in a phantom. These materials were printed using a variety of different additive manufacturing (3D Printing) techniques. PLA, a material with T1 values resembling bone was used to construct the outer shell of the phantom which takes the form of a 3D printed skull with a 50% fill base. The STL file for this skull was created using 3D Slicer, an open-source software, with a set of DICOM MRI images3. The prototype of the phantom shell is made from a hard PLA plastic, which has been shown to have a low, but visible MR signal at 3T. This hard PLA skull was printed in two parts, to allow access to the brain compartment. It features two small pegs to allow for consistent alignment of the skull halves. The bowl of the skull has been lined with anti-mould white silicone sealant, making it watertight.Results

Testing of all 3D printed materials was done using a Siemens Magnetom Prisma 3T MRI scanner. A pointwise encoding time reduction with radial acquisition (PETRA) (256 x 256, TR = 5ms, TE = 0.07ms, TA = 9s) sequence was used to visualise the blocks. The sequence (Fig 3) of the first 20 blocks of materials showed that even with an ultra-short TE, only ten materials were visible, two of which were rigid. Initial attempts to print with the most visible of these (ABS) failed due to insufficient printer bed temperatures, which resulted in poor adhesion.The first prototype skull (Fig 4) was then printed out of PLA. Testing of all 3D printed materials used a relaxometry technique, provided on the Prisma, to determine their T1 and T2 values. The Lay-Series of materials had been soaked in water for a week to remove the PVA component, which can create signal voids if left undissolved. Preliminary testing of materials on our Siemens 3T scanner showed good agreement in the T1 values of the LAYFOMM 40 (686 ± 62.3ms). Preliminary testing of the LAY-FELT materials showed a lower T1 than expected (768.3 ± 82.3), which is suspected to be linked to insufficient dissolving of the PVA component of the material.

Discussion

While no identical match to the T1 and T2 values of white and grey matter has been found, the results thus far are encouraging. The issues surrounding the poor dissolution of the PVA elements of the Lay series of materials can be overcome by using a heated ultrasonic water bath, per the manufacturers instructions.The investigation into the design and material capabilities afforded by 3D printing have provided results which indicate this is a viable method to produce an anthropomorphic head phantom, with a readily distributable design. The STL file for each of these prints would be open source. In the absence of a local 3D printer, they can be ordered from a 3D printing specialist for a fraction of the cost of current commercial phantoms.

Conclusions

Initial testing showed few of the commonplace 3D printed materials were appropriate for phantom production. That said, with the improvement of 3D printing technologies, the development of imaging specific materials is advancing. This project is still ongoing, awaiting funding for the completion of the prototype phantom with a brain insert, alongside imaging structures. Further research into the suitability of materials provided by other 3D printing methods, such as Polyjet technology, is required. Such printers would be capable of printing a phantom composed of multiple materials in a single print, removing the need for post-manufacture construction. While this project looks specifically at the construction of a head phantom, the results can be applied in other areas. Further work also includes investigations into phantoms of other anatomical areas, functional phantoms (such as 4D flow) as well as multi-modality phantoms.Acknowledgements

My thanks to the NHS GGC MRI Physics department for their ongoing support throughout this project, in particular my supervisors, Pauline Hall-Barrientos and David Brennan. Also to the Medical Devices Unit for their help in the manufacture of the prototype phantom, without their help and expertise this wouldn't have been possible. Finally, thank you to all the other NHS GGC departments and other organisations who provided me with sample materialsReferences

References: [1] He, Y et al (2019). Characterizing mechanical and medical imaging properties of polyvinyl chloride‐based tissue‐mimicking materials. Journal of applied clinical medical physics, 20(7), 176-183 .[2] Talalwa, Lotfi, et al. "T 1-mapping and dielectric properties evaluation of a 3D printable rubber-elastomeric polymer as tissue mimi cking materials for MRI phantoms." Materials Research Express 7.11 (2020): 115306.[3] Bullitt E, Zeng D, Gerig G, Aylward S, Joshi S, Smith JK, Lin W, Ewend MG (2005) Vessel tortuosity and brain tumor malignancy: A blinded study. Academic Radiology 12:1232-1240Figures

Fig 1. Segmentation of the skull in 3D slicer, creating an STL file with artificial supports.

Fig 2. The STL file simplified into fewer geometric surfaces to reduce file size. This STL file has specified fill densities and surface widths.

Fig 3. PETRA sequence of the first 20 blocks tested. The Yellow star indicates the signal from PLA, which was used to print the test skull.

Fig 4. The 3D printed shell of the phantom in ABS. Printed in two different segments to allow for filling with printed anatomical structures. This will be lined with silicone sealant to ensure it is water tight.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5222