5220

Development of a realistic human spine phantom to mimic static B0 field inhomogeneity in the cervical spinal cord1Department of Physics, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

Synopsis

Keywords: Phantoms, Spinal Cord, Susceptibility, Field inhomogeneity, High field MRI, Shims, Artifacts, Field simulation

Anthropomorphic phantoms could facilitate testing of novel MRI methods. This is especially important for spinal cord imaging at 7T, which is severely affected by local B0 field inhomogeneity due to susceptibility differences between tissues, particularly between bone and soft tissues. Here we built a 3D-printed model of vertebrae C3-C5, which was included in a spherical phantom. Measured field maps of the phantom were compared with simulations, showing similar features in the field distortion. The phantom also exhibited a spatially periodic pattern of signal drop-out around the intervertebral junctions in multi-echo GRE, similar to what is commonly observed in in-vivo data.Introduction

Innovation in MRI requires frequent testing of protocols and sequences. First-stage testing is mostly done on homogeneous phantoms. These phantoms, however, fail to represent key challenges encountered in vivo, related to human anatomy and physiology. Therefore, there is a need for anthropomorphic phantoms. This is particularly true for spinal cord imaging at 7T1,2 where in vivo data are heavily affected by B0 field inhomogeneity, due to differences in susceptibility between tissues. Specifically, the field inhomogeneities cause a periodic pattern of signal drop-out and geometric distortion around each intervertebral junction, which severely compromises anatomical, as well as functional, imaging. Slice-wise shimming techniques have been proposed to reduce the distortion and signal drop-out3,4 but substantial artifacts typically persist. In this work, our aim is to build an anthropomorphic MRI phantom of the human cervical spine to mimic the static B0 field distribution encountered in vivo. Such a phantom could then be used to optimize advanced shimming and acquisition techniques for 7T spinal cord MRI.Methods

The periodic B0 field pattern in the spinal cord likely originates from susceptibility differences between bone and soft tissues. Therefore, we 3D-printed an anatomically accurate model of cervical vertebrae. A schematic workflow of the proposed approach is presented in Figure 1. An STL template of vertebrae C3 to C5 was extracted from one subject in the public CT dataset VerSe5,6,7 using the modules Crop Volumes and Segment Editor in 3D Slicer8,9. The vertebrae were 3D-printed with a layer thickness of 0.1mm in standard White Resin (v4) by the Stereolithography (SLA) Form3B printer10 from FormLabs. The phantom consisted of a 15cm diameter plastic sphere filled with salt water (1.6L deionized water + 7.9g salt11), in which the vertebrae were suspended by two threads. Soap was added to avoid air bubble formation at the surface of the vertebrae. A B0 field map (FM) (1mm isotropic resolution, TR=1050.0ms, TE1=3.06ms, TE2=4.08ms, 2 averages) was acquired on a 7T Siemens Terra system. A multi-echo 2D GRE sequence (0.3x0.3x3.0mm resolution, 12 evenly spaced echoes between TE1=7.40ms and TE12=80ms) was acquired to measure signal loss. The background field of the FM was corrected with a homogeneous field and 3D linear gradients. Local field gradients along the z-direction were calculated by taking the difference between neighboring voxels. Before gradient calculation, the FM was smoothed by 3D gaussian filters (σfield_map=0.3mm, σgradient=0.75mm). The FM and gradients were compared to a simulation computed using a Fourier-based method12. Uniform susceptibility values were assigned to a mask of the vertebrae generated from acquired magnitude images. The mask was then multiplied with a dipole function in k-space, before being inverse transformed back to image space.Results

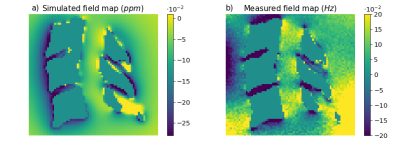

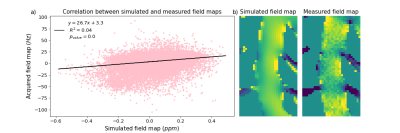

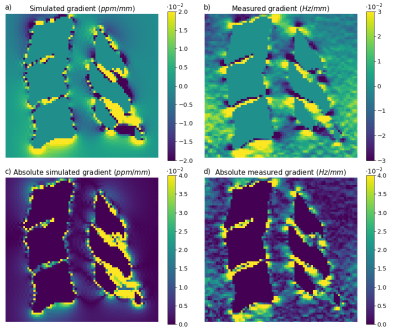

Qualitatively similar field patterns were observed in the simulated and acquired FMs (Fig. 2), with low fields between the vertebrae, and high fields in front of each spinal process, creating alternating fields along the spinal canal. A linear regression (Fig. 3) between the simulated and the measured fields showed a highly significant correlation (p<0.001), but also high variability (R2=0.043). The variability may be due to noise and residual background fields in the measured FM, as well as discretization errors close to bone/soft tissue interfaces in the simulated FM.Figure 4 shows the local field gradients in the z-direction. Alternating positive and negative field gradients were observed posteriorly in the spinal canal, around each intervertebral junction, in both measurement and simulation. The absolute value of the field gradient (Fig. 4c,d) showed zero points extending from the center of each intervertebral junction, with large local field gradients above and below.

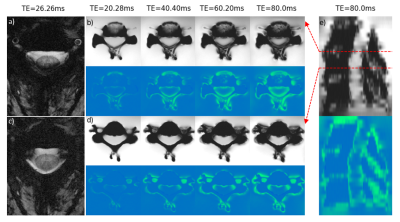

Figure 5 shows phantom multi-echo GRE images from two selected slices, just above the C3/C4 intervertebral junction, and mid-C4. For comparison, two slices (mid-C3 and just above C3/C4) from an in vivo acquisition are shown. The slices near an intervertebral junction show drop-out along the rim of the spinal canal, particularly towards the posterior edge. The slices centered on a vertebra instead suffer from drop-out coming in from the sides anteriorly. The sagittal view (Fig. 5e) shows the periodicity of the signal drop-out related to the vertebrae. A notable difference between phantom and in vivo data was that the signal loss appeared at earlier echo times in the in vivo data.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this work, we built an anthropomorphic MRI phantom of the human cervical spine, by 3D-printing a model of C3-C5 vertebrae generated from CT images. The phantom exhibited qualitatively similar local B0 field inhomogeneity as commonly observed in vivo, including similar patterns of signal drop-out in GRE acquisitions. However, the dropouts in the phantom images appeared at later echo times, indicating lower local field gradients. This implies that the magnetic susceptibility difference between the resin used for 3D-printing the vertebrae and the surrounding salt water was lower than between vertebrae and soft tissues in vivo. In future work, the phantom liquid will be modified to match the susceptibility differences. As a first proof-of-principle, this work demonstrates the feasibility of reproducing realistic B0 field patterns from the spine using a 3D-printed model. An anthropomorphic spine phantom may serve to test new acquisition strategies to tackle the persistent challenge of static B0 field distortion in spinal cord imaging.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Barry, R. L., Vannesjo, S. J., By, S., Gore, J. C., & Smith, S. A. (2018). Spinal cord MRI at 7T. NeuroImage, 168, 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.07.003

2. De Tillieux, P., Topfer, R., Foias, A., Leroux, I., El Maâchi, I., Leblond, H., Stikov, N., & Cohen-Adad, J. (2018). A pneumatic phantom for mimicking respiration-induced artifacts in spinal MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 79(1), 600–605.https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26679

3. Finsterbusch, J., Eippert, F., & Büchel, C. (2012). Single, slice-specific z-shim gradient pulses improve T2*-weighted imaging of the spinal cord. NeuroImage, 59(3), 2307–2315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.038

4. Islam, H., Law, C. S. W., Weber, K. A., Mackey, S. C., & Glover, G. H. (2019). Dynamic per slice shimming for simultaneous brain and spinal cord fMRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 81(2), 825–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27388

5. Liebl, H., Schinz, D., Sekuboyina, A., Malagutti, L., Löffler, M. T., Bayat, A., El Husseini, M., Tetteh, G., Grau, K., Niederreiter, E., Baum, T., Wiestler, B., Menze, B., Braren, R., Zimmer, C., & Kirschke, J. S. (2021). A computed tomography vertebral segmentation dataset with anatomical variations and multi-vendor scanner data. Scientific Data, 8(1), 284.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01060-0

6. Löffler, M. T., Sekuboyina, A., Jacob, A., Grau, A.-L., Scharr, A., El Husseini, M., Kallweit, M., Zimmer, C., Baum, T., & Kirschke, J. S. (2020). A Vertebral Segmentation Dataset with Fracture Grading. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, 2(4), e190138. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.2020190138

7. Sekuboyina, A., Husseini, M. E., Bayat, A., Löffler, M., Liebl, H., Li, H., Tetteh, G., Kukačka, J., Payer, C., Štern, D., Urschler, M., Chen, M., Cheng, D., Lessmann, N., Hu, Y., Wang, T., Yang, D., Xu, D., Ambellan, F., … Kirschke, J. S. (2021). VerSe: A Vertebrae labelling and segmentation benchmark for multi-detector CT images. Medical Image Analysis, 73, 102166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2021.102166

8. 3D Slicer image computing platform. (n.d.). 3D Slicer. Retrieved 8 November 2022, from https://slicer.org/

9. Fedorov, A., Beichel, R., Kalpathy-Cramer, J., Finet, J., Fillion-Robin, J.-C., Pujol, S., Bauer, C., Jennings, D., Fennessy, F., Sonka, M., Buatti, J., Aylward, S., Miller, J. V., Pieper, S., & Kikinis, R. (2012). 3D Slicer as an Image Computing Platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 30(9), 1323–1341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001

10. Form 3B+: Industrial-Quality Dental 3D Printer. (n.d.). Formlabs. Retrieved 8 November 2022, from https://dental.formlabs.com/products/form-3b/

11. Bennett, D. (2011). NaCl doping and the conductivity of agar phantoms. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 31(2), 494–498.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2010.08.018

12. Schäfer, A., Wharton, S., Gowland, P., & Bowtell, R. (2009). Using magnetic field simulation to study susceptibility-related phase contrast in gradient echo MRI. NeuroImage, 48(1), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.093

Figures