5169

Determination of optimal parameters for accelerated whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging (WB-DWI) using simultaneous multi-slice (SMS)1MRI Unit, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, Sutton, United Kingdom, 2Division of Radiotherapy and Imaging, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom, 3MR Application Predevelopment, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Whole Body, Simultaneous Multi-Slice

Simultaneous multi-slice (SMS) has the potential to accelerate whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging (WB-DWI). This work presents quantitative and qualitative assessment of SMS image quality in phantoms and healthy volunteers, as a strategy to determine the optimal parameters for the clinical application of a research application SMS sequence.

An SMS factor of 2 and a moderately reduced TR did not introduce significant bias to ADC measurements. The reduction in SNR for these acquisitions was statistically, but not clinically, significant. These parameters offer time savings of up to 24% with respect to non-SMS settings and should be investigated further in a patient population.

Introduction

Whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging (WB-DWI) is a sensitive technique for detecting and characterising malignant bone disease. Despite long acquisition times, it increasingly provides cancer screening for at-risk populations1.Simultaneous multi slice (SMS) imaging accelerates acquisition by acquiring several slices simultaneously with multi-band RF pulses and phased-array coils2. Reduced acquisition times with SMS have been demonstrated without compromising image quality3, although bias in apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) estimates has been reported4, 5.

This work presents a framework for determining the optimal parameters for SMS imaging in WB-DWI in terms of the compromise between faster acquisition, image quality and ADC bias. This is demonstrated with a research application sequence combining SMS with interleaved short inversion time inversion recovery (STIR) fat suppression6.

Methods

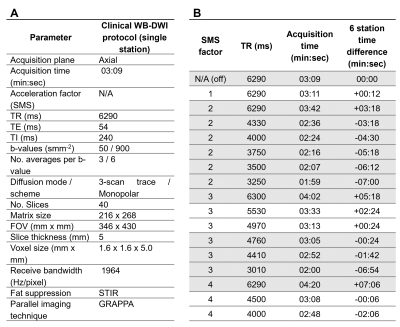

Single-station images were acquired in phantoms and healthy volunteers with increasing acceleration via higher SMS factors (2-4) and reduced TR (6300-3010ms), as detailed in figure 1, and compared to images acquired with the clinical STIR-WB-DWI protocol. Volunteer studies were approved by an Institutional Review Board and all volunteers gave written informed consent. Images were acquired on a 3T scanner (MAGNETOM Vida, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a research application pulse sequence.The phantom7 consisted of two sections with ADC values of 1000 10-6mm2s-1 and 1500 10-6mm2s-1. A spherical ROI was defined across a six-slice region and the subtraction method8 used to calculate SNR. Further ROIs were defined across a four-slice region in each section and median ADC values were calculated.

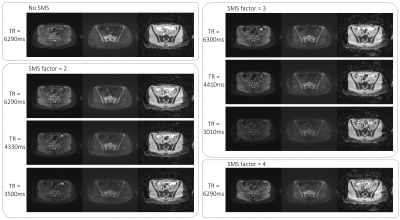

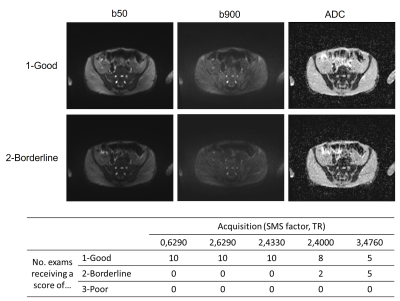

Single-station pelvic images were acquired from 10 healthy volunteers (male/female: 5/5, mean age=33.5years ±9.2years) using a subset of the phantom parameter sets, selected based on their performance in phantoms and potential to reduce acquisition time. A radiologist graded the clinical image quality of a subset of volunteer images on a three-point Likert scale (good/borderline/poor).

An ROI was defined within gluteal muscle over 3 slices and a second ROI was defined within the vertebral bone marrow of S1 for 1 slice. SNR was calculated for the gluteal ROIs and median ADC was calculated for the gluteal and bone marrow ROIs.

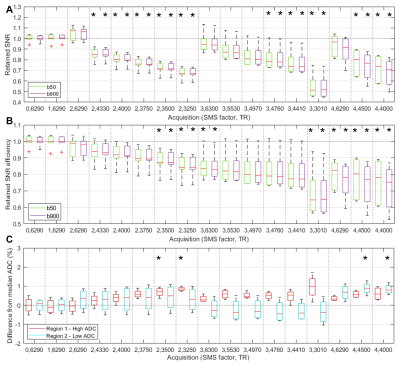

SNR variation was considered in terms of retained SNR9, and SNR efficiency (SNR/square root of acquisition time)10 relative to the clinical standard. The slice-to-slice SNR variation was assessed for volunteer images using the ratio of standard deviation to mean SNR.

The statistical significance of differences from the clinical standard was assessed using Friedman tests and, where group differences were found, a Wilcoxon paired ranks test with Bonferroni correction.

Results

Figure 2 illustrates the variation in SNR and ADC across the phantom acquisitions. Statistically significant reductions in SNR were found for all acquisitions with a TR of less than 5000ms. When TR was maintained, higher SMS factors did not result in a significant reduction in SNR. All measured phantom ADC values were within ±2.0% of the clinical standard.The effect of different parameters on volunteer image quality is illustrated in figures 3 and 4. SNR and SNR efficiency are reduced with lower TRs but are maintained with higher SMS factors and constant TR. The slice-to-slice SNR variation increases with lower TR and higher SMS factor. There were no statistically significant differences in ADC, except for in bone marrow with an SMS factor of 4.

Radiological image scoring is summarised in figure 5. None of the images assessed were rated as poor.

Discussion and Conclusions

To be a viable option for accelerating WB-DWI, SMS must produce images of equivalent diagnostic quality to the clinical standard and without significant bias in measured ADC values.SMS factors of up to 4 did not reduce SNR or SNR efficiency, suggesting that the multi-band RF pulses themselves do not affect SNR. The TR reduction required to accelerate acquisition did however affect SNR in both phantoms and volunteers.

A statistically significant reduction in SNR is not necessarily clinically significant and the radiological image scoring suggests TR reduction does not affect image quality when the SMS factor is 2 and the TR is greater than 4000ms. Slice-to-slice SNR variation increases with increasing SMS factor, introducing greater variability in image quality across the station. For SMS factors of 2 or 3, no significant ADC bias was introduced.

These results suggest that an SMS factor of 2 with a TR of 4000-4500ms is a promising set of parameters for further investigation. The reduced SNR does not appear to have a clinically significant effect on image quality and there was no statistically significant ADC bias in healthy tissue. A TR of 4000ms with SMS factor of 2 offers a 24% reduction in acquisition time, corresponding to a saving of 4 minutes 30 seconds for a six-station WB-DWI examination. Greater reductions in TR offer further acceleration at the expense of a potentially clinically significant loss in SNR.

Although volunteer images provide an indicator of quality, evaluation in patient populations is required to assess lesion conspicuity and effect on pathological ADC estimates.

SMS offers significant reduction in acquisition time but acceleration to the maximum extent results in loss of SNR and bias to ADC measurements. This work has presented a strategy to determine the optimal compromise between acquisition time and image quality, identifying a set of parameters for further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This project represents independent research funded by Cancer Research UK National Cancer Imaging Translational Accelerator (NCITA), the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre and the Clinical Research Facility in Imaging at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and The Institute of Cancer Research, London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

We thank Siemens Healthineers for providing the DW imaging research application package.

References

1. Petralia, G., Koh, D.-M., Attariwala, R., Busch, J.J., et al., Oncologically relevant findings reporting and data system (ONCO-RADS): guidelines for the acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of whole-body MRI for cancer screening. Radiology, 2021. 299(3): p. 494-507.

2. Obele, C.C., Glielmi, C., Ream, J., Doshi, A., et al., Simultaneous multislice accelerated free-breathing diffusion-weighted imaging of the liver at 3T. Abdominal imaging, 2015. 40(7): p. 2323-2330.

3. Glutig, K., Krüger, P.-C., Oberreuther, T., Nickel, M.D., et al., Preliminary results of abdominal simultaneous multi-slice accelerated diffusion-weighted imaging with motion-correction in patients with cystic fibrosis and impaired compliance. Abdominal Radiology, 2022: p. 1-12.

4. Kenkel, D., Barth, B.K., Piccirelli, M., Filli, L., et al., Simultaneous multislice diffusion-weighted imaging of the kidney: a systematic analysis of image quality. Investigative Radiology, 2017. 52(3): p. 163-169.

5. Weiss, J., Martirosian, P., Taron, J., Othman, A.E., et al., Feasibility of accelerated simultaneous multislice diffusion‐weighted MRI of the prostate. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2017. 46(5): p. 1507-1515.

6. Stemmer, A., Horger, W., and Kiefer, B. Whole-Body STIR Diffusion-Weighted MRI in One Third of the Time. in Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Medicine 21st Annual Meeting. 2013.

7. HQ Imaging. DWI Phantom. [cited 2022 16/09/2022]; Available from: http://hq-imaging.com/dwi-phantom.

8. National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA), NEMA Standards Publication MS 1-2008 (R2014, R2020): Determination of Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in Diagnostic Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2021.

9. Stemkens, B., Sbrizzi, A., Andreychenko, A.A., Crijns, S.P., et al., An optimization framework to maximize signal‐to‐noise ratio in simultaneous multi‐slice body imaging. NMR in Biomedicine, 2016. 29(3): p. 275-283.

10. Parker, D.L. and Gullberg, G.T., Signal‐to‐noise efficiency in magnetic resonance imaging. Medical Physics, 1990. 17(2): p. 250-257.

Figures