5161

Imaging of Propagating Broadband Transient Waves with Multi-scale MR Elastography Motion Encoding: A Validation Study

Yuan Le1, Jun Chen1, Phillip J. Rossman1, Armando Manduca1, Kevin J. Glaser1, Bradley D. Bolster Jr.2, Stephan Kannengiesser3, and Richard L. Ehman1

1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2US MR R&D Collaboration, Siemens Medical Solutions Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, United States, 3MR Application Predevelopment, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany

1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2US MR R&D Collaboration, Siemens Medical Solutions Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, United States, 3MR Application Predevelopment, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Elastography, Elastography, Transient wave, multi-scale encoding

We demonstrate imaging of the propagation of transient waves using multi-scale motion encoding gradient waveforms. Displacement values are calculated using the inverse Haar transforms. We validated the results by comparison with wave images obtained using standard MRE acquisition and processing. The approach provides the ability to image broadband motion more efficiently and accurately compared with previous methods and promises to be a useful approach for biomechanical studies of traumatic brain injury.Introduction

MR Elastography (MRE) has an expanding clinical role, particularly for noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis1. New applications for brain and cardiac imaging are also emerging. Standard MRE techniques acquire images of propagating harmonic shear waves in a steady state2, 3. Several repetitions are acquired, using a fixed motion encoding gradient (MEG) shape and a varying phase relationship with the applied motion, so that a series of images is acquired at different phases of the propagating wavefield. It is also possible to image broadband or transient mechanical waves as they propagate through organs4. This information is useful, for instance, in biomechanical studies of the distribution of traumatic brain lesions resulting from external mechanical transients. However, using standard MRE methods it is necessary to carefully balance the bandwidth and the sensitivity of the MEG and design proper deconvolution techniques for transient applications5, which is not always practical when the motion frequency range is unknown. We have developed a more efficient approach for transient wave imaging6, using multiple scale Haar wavelet-based motion encoding gradients to detect motion of a broader bandwidth, such as in transient MRE4, 7-11. With this technique a high motion sensitivity is achievable over a wide frequency range, and the displacement can be reconstructed with a simple inverse Haar transform. In this study, we validated the technique by comparison with results of the standard transient MRE.Methods

Both multi-scale MRE and standard MRE research sequences were based on a spin-echo EPI sequence and with 3D motion encoding. Data were acquired at a 3T clinical scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a PVC gel phantom. Table 1 lists the imaging parameters. The details of the multi-scale MRE sequence and displacement map reconstruction were explained in our previous abstract6. Three scales of Haar wavelet plus a scaling function were used for MEG in multi-scale MRE: the 36ms bipolar MEG detected the difference in the DC value between consecutive 18ms-windows. Cumulative sums of the acquired phase difference were then used as scaling function elements. 18ms, 9ms and 4.5ms MEG were used for 3 wavelet scales. The MEG amplitude was 10, 10, 14.1 and 20mT/m, respectively. Ten sampling windows were acquired so the total sampled time duration was 180ms. Two types of transient motion waveforms were generated using a pneumatic driver (Resoundant Inc., Rochester MN, USA) for this study: (1) one cycle of a 90-Hz sinusoidal wave; and (2) ten cycles of 90-Hz sinusoidal waves. With multi-scale MRE, displacement was calculated at each voxel. The calculated displacement was then convolved with the MEG profile used in standard MRE. The result was a simulated standard MRE phase difference using the calculated displacement as the ‘truth’. These simulated phase difference values were then compared to the phase difference acquired with standard MRE. Finally, a Fourier transforms were performed on the displacement in the phase encoding direction both over the total time duration for the spectrum analysis, and over every 100ms time intervals overlapped (0-100ms and 50-150ms) for a spectrogram analysis.Results

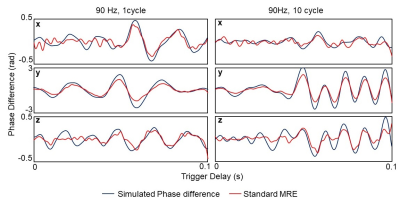

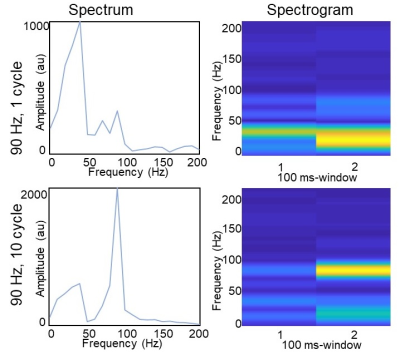

An example of phase difference maps from multi-scale MRE is displayed in Figure 1. The wave motion detected using the 4.5ms MEG has a shorter wavelength than those detected using longer MEG, reflecting the sensitivity to higher frequencies. The displacement at one example voxel (yellow dot in Figure 2) was found to change in both amplitude and frequency during the 180ms sampling window, with both one and ten 90Hz wave cycles. As shown in Figure 3, the simulated phase differences were slightly higher with both types of transient motion and all three motion directions, but the shapes of the waveforms matched very well in general. The spectrum and the spectrogram in Figure 4 shows that with the stimulation of only one 90Hz motion cycle, the response was a broadband motion with a much lower peak frequency of around 40Hz; while with ten 90Hz cycles, the response initially started with a lower frequency (around 40Hz) but later reached 90Hz.Conclusions

The simulated phase difference from multi-scale MRE matched very well with acquired phase difference of standard MRE, indicating that the multi-scale MRE accurately detected any motion within the bandwidth of that standard MEG. The simulated phase difference was slightly higher, which might be caused by the different non-linearity in the MEG profile in the two methods. Spectrum analysis showed a very realistic frequency response during the selected time-window. These results indicate that multi-scale MRE is a promising technique in applications such as tissue biomechanical studies related to traumatic brain injury. Future studies include transient brain motion detection in healthy volunteers.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from National Institutes of Health R01EB001981.References

- Yin, M., et al. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43(7):1546-51. Epub 2017/10/11.

- Litwiller, D. V., et al. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2012;8(1):46-55.

- Muthupillai, R., et al. Science. 1995;269(5232):1854-7. Epub 1995/09/29.

- McCracken, P. J., et al. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(3):628-39. Epub 2005/02/22.

- Solanas, P. S., et al. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2021;34(2).

- Le, Y., et al. Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB; London, England, UK.

- Souchon, R., et al. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(4):871-81. Epub 2008/09/26.

- Hofstetter, L. W., et al. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81(5):3153-67. Epub 2019/01/22.

- Hofstetter, L. W., et al. Phys Med Biol. 2020. Epub 2020/12/23.

- Smith, D. R., et al. J Biomech Eng-T Asme. 2020;142(7).

- Shahryari, M., et al. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2021;85(4):1962-73.

Figures

Table 1. Imaging parameters for multi-scale MRE and standard transient

wave MRE.

Figure 1. A series of phase difference maps (gray scale

movies) were acquired at each MEG level (from top to bottom: 9 phase offsets

from 36ms scaling function alternative, 10 from 18ms, 20 from 9ms, and 40 from

4.5ms wavelet function). Final displacement maps are shown as the pseudo-color

wave movie.

Figure 2. Displacement curve at one voxel (yellow dot) with

one and ten cycles of applied 90Hz vibration.

Figure 3. Simulated phase differences derived from multi-scale MRE match

very well with the acquired phase differences from standard MRE

Figure 4. (Left) Spectrum of the displacement curve derived

from multi-scale MRE over the full 180 ms window. (Right) Spectrogram of the

displacement over separate 0-100ms and 50-150ms time windows.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5161