5158

Sagittal free-breathing MR elastography of the pancreas with motion-correction at 3T1Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2Imaging and Biomarkers, Cancer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3Endocrinology, Metabolism, Amsterdam Gastroenterology, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Elastography, Pancreas

Breathing motion can be detrimental to quantitative accuracy in pancreatic MR elastography (MRE). We investigated motion-correction strategies on sagittal multi-frequency free-breathing SE-EPI MRE acquisitions to mitigate breathing-motion and increase accuracy. Breathing-states were determined through a respiratory-belt and multiple number of bins were tested. Three intensity-based registration methods (with and without non-rigid post-processing) and non-rigid registration were ranked on MRE quality measures. The best method showed improved data quality, inversion precision and repeatability compared to no correction, but resulted in apparently increased shear wave speed (SWS), which warrants further investigation.Introduction

Pancreatic MR elastography (MRE) is a non-invasive MR technique that is able to quantify visco-elastic properties of tissue, e.g. assessment of pancreatitis, benign or malignant tumors.1-3 Breathing motion can be detrimental to quantitative accuracy in MRE, particularly in the pancreas. Breathing mitigation techniques, such as repeated breath-holding, are used to overcome this. However, this can be particularly uncomfortable for patients, prolongs protocol time and limits data richness.4 Multi-frequency MRE allows for time-efficient and highly-resolved stiffness maps in free-breathing.5 However, the pancreas moves substantially with respiration, potentially hampering accurate analysis due to misalignment over the additional dimensions of the MRE acquisition (motion-encoding-gradient direction and wave-offsets).Pancreatic MRE is typically performed in an axial orientation to match anatomical scans. Approaches have been explored to correct respiratory motion in single-shot echo-planar-imaging (SE-EPI)4, but they have not considered both foot-head and anterior-posterior motion, both of which are present and substantial in the pancreas. A sagittal acquisition is more conducive to resolving these motions and therefore, we investigated motion-correction strategies on sagittal multi-frequency free-breathing SE-EPI MRE acquisitions.

Methods

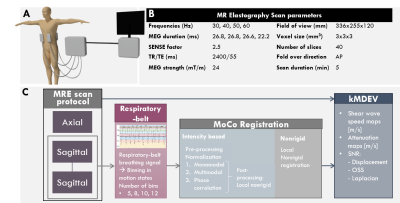

All scanning was performed at 3T (Ingenia,Philips,Best,Netherlands) using a multi-slice, multi-frequency SE-EPI MRE sequence at four mechanical frequencies (30,40,50,60Hz) introduced using four pneumatic drivers (figure 1A).5 Acquisition parameters can be found in figure 1B. Six healthy volunteers (3♀, age=29±3years) underwent one axial and two consecutive sagittal MRE acquisitions for repeatability analysis. A respiratory belt (PEAR-belt, Philips) was placed on the lower abdomen to record the respiratory signal throughout each scan. MRE data was cropped (50% both in feet-head and anterior-posterior) before motion-correction.Three intensity-based registration methods were tested (figure 1C): monomodal, multimodal and phase-correlation, using a regular step-gradient-descent-optimizer, one-plus-one revolutionary-optimizer and windowing in the frequency-domain, respectively. Pre-processing normalization and similarity-registration were applied for all three methods. Results with and without post-processing using non-rigid local registration were compared. Lastly, a stand-alone non-rigid registration was used.

MRE data were binned into respiratory motion-states (nBins) as determined from the respiratory belt signal (nBins=5/8/10/12). All motion-states were registered to end-expiration state using the aforementioned motion-correction methods applied on the magnitude images, after which the geometric translations were imposed on the real and imaginary parts of the complex data. Shear-wave-speed (SWS) was calculated using the kMDEV inversion algorithm.6

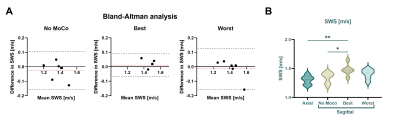

Regions-of-interest (ROIs) were manually drawn over the pancreas on end-expiration magnitude-data. Quality parameters were: (1) Displacement signal-to-noise (Displ-SNR)7, (2) Lap-SNR: the variance (σ) of the Laplacian (Δ) of the images4, (3) octahedral-shear-strain SNR (OSS-SNR)7, (4) stability: defined as intensity change over time of ROI boundary-voxels and (5) ratio of SWS and standard deviation (STDEV) within the ROI. Rank-scores were given for each motion-correction method for all quality parameters with the sum resulting in an overall-ranking. The best and worst method were compared to non-motion-corrected SWS for axial and sagittal scans using a repeated measures ANOVA and pairwise comparison with Bonferroni correction (p<0.05 was deemed significant). Repeatability was assessed using Bland-Altman analysis.

Image registration and analysis, delineation and statistical analysis were performed in Matlab (R2021b,Mathworks,Natick,MA,USA), ITK-snap (v3.8.0) and SPSS (version8) respectively.

Results

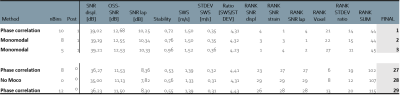

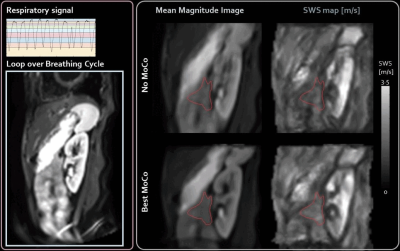

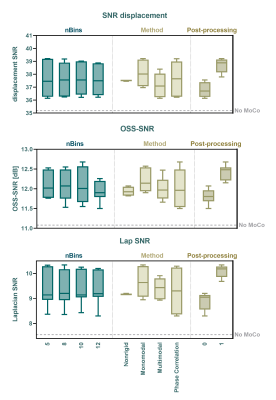

A total of 28 different combinations: nBins, registration methods (MoCo) and post-processing in the case of intensity based MoCo, were ranked together with no MoCo for all quality measures, see table 1. The best method was phase-correlation with nBins=10 and non-rigid post-processing. The worst scoring method was phase-correlation registration with nBins=12 and no motion-correction was 28th. Representative images of the best method can be found in figure 2. The average SNR-values per nBins, MoCo and post-processing are shown in figure 3. Bland-Altman analysis showed 95%-limits-of-agreement of [-0.16, 0.10], [-0.06 0.09] and [-0.16, 0.17] m/s for no MoCo, best and worst respectively, see figure 4. The average SWS for all volunteers was 1.30±0.07, 1.37±0.10, 1.48±0.10 and 1.41±0.09m/s for axial, no MoCo, best and worst respectively (F(5,15)=9, p<.001). Pairwise comparison showed significant differences between best MoCo, axial and sagittal no MoCo (p<.05), see figure 4.Discussion

Here we show that motion-correction increases precision in MRE inversion. In particular, phase-correlation with non-rigid post-processing in 10 respiratory bins showed the best performance. nBins does not have a large effect on registration quality overall, though increasing nBins beyond some threshold would eventually degrade registration. Post-processing showed increased performance, which may be due to the local registration. Multimodal-intensity can register images with different contrast, making it robust for different imaging modalities, however for MRE (single-contrast) it could introduce errors.Contrary to recent work, which performed motion-correction of coronal abdominal MRE at 1.5T using a 2D rigid-body image registration method4, our work showed increased apparent SWS after motion-correction. This observation needs further analysis, preferably within a moving phantom with known stiffness inclusions to eliminate causation by MoCo.

Bland-Altman analysis showed an increased repeatability after using the best performing MoCo method, whilst the worst performing showed decreased repeatability, with wider limits-of-agreement comparable to no MoCo. This may have implications on future clinical findings – particularly in smaller tissues such as the pancreas for improved quantification of the heterogeneous tumor microenvironment.

Conclusion

Motion-correction in sagittal free-breathing SE-EPI pancreatic MRE is promising, with improved data quality, inversion precision and repeatability compared to no correction, but the increased apparent shear wave speed within the pancreas warrants further investigation.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Zhu L, Guo J, Jin Z, et al. Distinguishing pancreatic cancer and autoimmune pancreatitis with in vivo tomoelastography. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(5):3366-3374. doi:10.1007/s00330-020-07420-5

2. Gültekin E, Wetz C, Braun J, et al. Added value of tomoelastography for characterization of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor aggressiveness based on stiffness. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(20). doi:10.3390/cancers13205185

3. Shi Y, Cang L, Zhang X, et al. The use of magnetic resonance elastography in differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A preliminary study. Eur J Radiol. 2018;108:13-20. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.09.001

4. Shahryari M, Meyer T, Warmuth C, et al. Reduction of breathing artifacts in multifrequency magnetic resonance elastography of the abdomen. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85(4):1962-1973. doi:10.1002/mrm.28558

5. Dittmann F, Tzschätzsch H, Hirsch S, et al. Tomoelastography of the abdomen: Tissue mechanical properties of the liver, spleen, kidney, and pancreas from single MR elastography scans at different hydration states. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78(3):976-983. doi:10.1002/mrm.26484

6. Tzschätzsch H, Guo J, Dittmann F, et al. Tomoelastography by multifrequency wave number recovery from time-harmonic propagating shear waves. Med Image Anal. 2016;30:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.media.2016.01.001

7. Bertalan G, Guo J, Tzschätzsch H, Klein C, Barnhill E, Sack I, Braun J. Fast tomoelastography of the mouse brain by multifrequency single-shot MR elastography. Magn Reson Med. 2019 Apr;81(4):2676-2687. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27586. Epub 2018 Nov 4. PMID: 30393887.

Figures