5146

Realistic simulated MR Elastography data generated from in vivo brain images1Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, United States, 2University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 3University of Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Elastography, In Silico

Simulations can play an important role in validating the accuracy of MR elastography (MRE) inversion algorithms. A realistic brain MRE simulation is created through a finite element model from in vivo MRE data, with 20 randomly generated simulated brains created by assigning properties of anatomical segmentations of brain structures within a range given by a published MRE atlas. Multi-frequency and multi-direction synthetic MRE data was generated via boundary conditions from in vivo measured motions to allow a range of inversion algorithms to be tested. These data will be supplied to the MRE study group for an inversion reconstruction challenge.Introduction

MR elastography (MRE) provides quantitative images of the mechanical properties of tissue, with promising applications in a range of tissues including liver, brain, muscle, kidney, and others1. Typical MRE techniques apply a harmonic vibration to the tissue and measure the steady-state vibration field using motion encoding gradients. An inversion algorithm is then used to estimate the mechanical properties. Many candidate inversions have been proposed over the past 27 years of MRE literature, and the field has not converged on a single methodology. Even within a single research group, different algorithms are sometimes used for different applications (often recovering different property values), and more complex constitutive models are being investigated, potentially pushing the limits of what is detectable from the available data. Spatial and quantitative accuracy is a goal of MRE acquisition and inversion, and it is useful to evaluate accuracy of inversion algorithms in a setting where the ‘true’ answer is known. Experimental phantoms have proven useful; however, fabricating a phantom with the same structural complexity as expected in vivo is difficult, and material selection and independent mechanical testing methods must be carefully controlled and themselves have uncertainty and bias due to methodological factors. Numerical simulations can more easily be used to generate realistic MRE data in organ-mimicking geometries where the ‘true’ properties and underlying mechanical behavior are precisely known2,3. A range of mechanical models can be used, and experimental uncertainties such as distortion and realistic MRI noise models can be added4,5. Here we present a series of simulations with a range of ground truth values that are generated to characterize the performance of MRE inversions.Methods

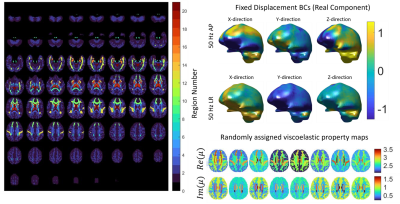

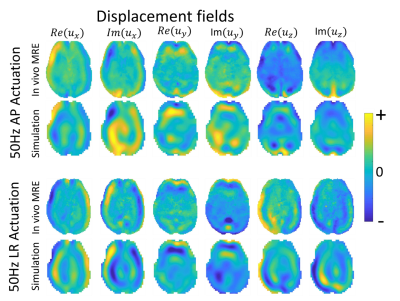

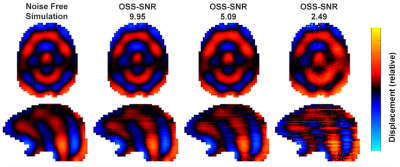

Realistic brain MRE simulations are built from in vivo MRE datasets. A full-brain MRE protocol was collected on a 3T Siemens Prisma from a healthy volunteer (23F) to build the finite element model (FEM). The subject maintained the same position for the entire imaging protocol. A series of 2x2x2mm MRE datasets were acquired with a 3D multiband, multishot spiral MRE sequence6. Vibrations were applied to the head using a Resoundant pneumatic actuator with pillow driver (AP excitation). Separate MRE datasets were collected at 30, 40, 50, and 60 Hz, with an additional dataset at 50 Hz with vibrations applied laterally (LR excitation)7 to allow both multi-frequency and multi-direction inversions to be tested. Each MRE scan took 3:35 to acquire. T1-weighted images were collected with a 0.9 mm MPRAGE sequence to generate atlas-based segmentations of gray matter, white matter, subcortical gray matter, and white matter tracts, which are used to define the geometry of the FEM. Diffusion MRI data at 1.5 mm (128 directions; b = 1500 and 3000 s/mm2) also collected to estimate axonal fiber direction and allow transverse isotropic models to be applied. All data was interpolated to 1.6 mm resolution to create the highest resolution, whole-brain FEM within memory limitations.Assigned properties for different structures in the simulation were determined from the 10th and 90th percentiles of shear stiffness and damping ratio values taken from a published MRE atlas8, and this range was increased 1.5x to account for incomplete contrast recovery. Twenty random brain property distributions were generated by uniform sampling within these limits for each tissue class. Measured MRE displacements were applied as boundary conditions around the exterior of the simulated brain (at each of the actuation conditions), with the bottom surface near the brainstem left stress-free to avoid unrealistically high volumetric strains, and the FEM system was solved assuming a nearly incompressible (K=109 Pa) heterogenous viscoelastic mechanical model. The resulting complex-valued displacement fields were interpolated back to the original 2 mm voxels to simulate finite resolution MRE measurements. Data required to implement subject-specific MRI noise models was collected at the time of imaging following Hannum et al5 and can be added to the simulated displacement data for more realistic conditions, or simple Gaussian noise can be added.

The simulated data will be made available for a reconstruction challenge being organized by the ISMRM MRE study group and available at github.com/mechneurolab.

Results and Discussion

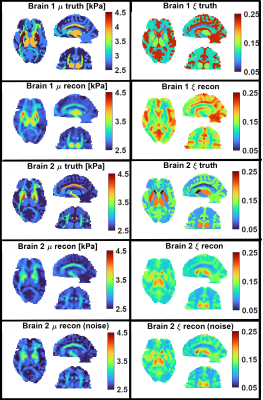

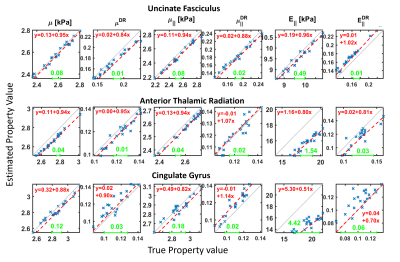

Figure 1 shows the geometry of the FEM with 12 white matter tracts, 6 subcortical grey matter regions, white/grey matter tissue classes, and ventricles. Examples of viscoelastic property maps for 8 of the 20 randomly generated brains are also shown, along with boundary conditions taken from measured data. The simulation generates synthetic motion maps with known ground truth properties that are qualitatively similar to in vivo MRE measurements (figure 2), ensuring that analysis of this simulated data is relevant to clinical brain MRE. Realistic, subject specific noise, incorporating contributions from imaging and physiological sources5 that give rise to correlated noise and slice-to-slice phase variations9,10, are added randomly to the data to achieve a range of different OSS-SNR11 values (figure 3). The spatial accuracy of MRE inversion algorithms can be tested, such as the nonlinear inversion (NLI)12 example in figure 4. Finally, the ensemble of 20 random brains can characterize inversion performance – accuracy and precision – by deviations in the ground truth vs recovered value plots of various structure-property combinations as shown in figure 5.Acknowledgements

NIH/NIBIB grant R01-EB027577.References

1. Manduca, A. et al. MR elastography: Principles, guidelines, and terminology. Magn. Reson. Med. 85, 2377–2390 (2021).

2. McGarry, M. D. J. et al. A heterogenous, time harmonic, nearly incompressible transverse isotropic finite element brain simulation platform for MR elastography. Phys. Med. Biol. 66, 055029 (2021).

3. Hiscox, L. V., McGarry, M. D. J. & Johnson, C. L. Evaluation of cerebral cortex viscoelastic property estimation with nonlinear inversion magnetic resonance elastography. Phys. Med. Biol. 67, 95002 (2022).

4. McIlvain, G., McGarry, M. D. J. & Johnson, C. L. Quantitative Effects of Off-Resonance Related Distortion on Brain Mechanical Property Estimation with Magnetic Resonance Elastography. NMR Biomed. 35, e4616 (2022).

5. Hannum, A. J., McIlvain, G., Sowinski, D., McGarry, M. D. J. & Johnson, C. L. Correlated Noise in Brain Magnetic Resonance Elastography. Magn. Reson. Med. 87, 1313–1328 (2022).

6. McIlvain, G., Cerjanic, A. M., Christodoulou, A. G., McGarry, M. D. J. & Johnson, C. L. OSCILLATE: A low-rank approach for accelerated magnetic resonance elastography. Magn. Reson. Med. 1–14 (2022) doi:10.1002/mrm.29308.

7. Smith, D. R. et al. Anisotropic mechanical properties in the healthy human brain estimated with multi-excitation transversely isotropic MR elastography. Brain Multiphysics (2022).

8. Hiscox, L. V et al. Standard-space atlas of the viscoelastic properties of the human brain. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 5282–5300 (2020).

9. Barnhill, E. et al. Fast Robust Dejitter and Interslice Discontinuity Removal in MRI Phase Acquisitions: Application to Magnetic Resonance Elastography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 1578–1587 (2019).

10. Murphy, M. C. et al. Phase Correction for Interslice Discontinuities in Multislice EPI MR Elastography. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Res. Med. 3426 (2012).

11. McGarry, M. D. J. et al. An octahedral shear strain-based measure of SNR for 3D MR elastography. Phys. Med. Biol. 56, N153–N164 (2011).

12. McGarry, M. et al. Multiresolution MR elastography using nonlinear inversion. Med. Phys. 39, 6388–6396 (2012).

Figures