5143

Vibration Exposure in Brain MR Elastography1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2Resoundant, Inc., Rochester, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Safety, Brain, Elastography

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) requires application of mechanical vibrations to assess the stiffness of tissue noninvasively and quantitatively. This study assessed the levels of vibration exposure in brain tissue during a typical brain MRE exams performed for clinical research. Voxel-level vibration exposure levels throughout the brain were measured in 45 subjects in this IRB approved study. Histograms of voxel-level vibration in all cases demonstrated maximum exposure levels that were well below the very conservative EU 2002 Directive 2002/44/EC of the European Parliament guideline for total body vibration.INTRODUCTION:

A growing number of studies have shown that magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) has promising applications in evaluating neurologic diseases, including preoperative assessment of brain tumors and providing new biomarkers for characterizing neurodegenerative diseases [1]. In these applications, low-amplitude vibrations are applied to head during imaging to generate propagating shear waves in the brain, at a typical frequency of 30-90 Hz. A modified phase contrast sequence is used to image the waves and these data are processed to generate quantitative images of tissue stiffness and other mechanical properties. Early testing showed that the amplitude of mechanical waves generated within the body (liver, kidney, breast, muscle, and brain) by the driver systems used in most MRE studies are well within existing guidelines for vibration exposure [2]. Given the expanding interest in brain imaging applications of MRE, the goal of this study was to conduct a more comprehensive assessment of vibration exposure levels generated by a prototype brain MRE driver system that is used at more than 50 locations worldwide.METHODS:

In this IRB-approved retrospective study, data were accessed from brain MRE exams in 45 subjects. All exams were performed Brain displacement data from 45 patients in an IRB-approved study were used for this retrospective study. The study was performed using a compact 3T MR scanner [2], [3]. The system employed the standard active driver (Resoundant Inc.) used in regulatory-approved versions of MRE, coupled via plastic tubing to a soft pillow-like passive driver to apply low-amplitude vibrations to the head (figure 1). In all 45 exams, the active driver power was adjusted to achieve suitable shear wave illumination of the brain.Full volume 3D vector MRE acquisitions of the brain were performed, using a dual-sensitivity and dual-motion encoding (DSDM) MRE sequence [4]. The MRE phase was unwrapped first, then the data were Fourier transferred to calculate the first harmonic of x-, y-, and z-displacements. The full displacement was calculated as the combined amplitude (square root of the sum of squares) of the first harmonic of the complex x-, y-, and z-axis shear waves. Automatic brain segmentation was performed using the FSL brain extraction tool. The local wave amplitude was computed on a voxel basis over the entire brain mask for each subject. Displacements were converted to RMS acceleration as follows:

Local sinusoidal motion of brain tissue with amplitude d and angular frequency $$$\omega = 2\pi f$$$, can be represented as:

$$$x\left(t\right)=d\times \sin\left(\omega t\right)$$$ (1)

and RMS acceleration of the motion can be calculated as:

$$$a_{rms}=\frac{a_{max}}{\sqrt{2}}=\frac{\omega^{2}d}{\sqrt{2}}=\frac{4\pi^{2}f^{2}d}{\sqrt{2}}$$$ (2)

Most standards for whole body vibration exposure are based on comfort and human performance criteria and define limits that are far below vibrations levels that might cause acute injury. The commonly-referenced EU 2002 Directive 2002/44/EC of the European Parliament suggests a maximum daily (8 hr) exposure limit of 1.15 $$$\left(m/s^{2}\right)$$$ [5]. The adjustment for durations other than 8 h is as follows [2]:

$$$a_{rms, T}=a_{rms, 8hr}\sqrt{\frac{8}{T}}$$$ (3)

In this study we evaluate an exposure limit for duration of 10 minutes, which is conservative, as most MRE acquisitions are less than 6 minutes in duration. Using equation (3), the adjusted exposure guideline for 10 minutes is $$$a_{rms, 10min}=$$$ 8 $$$\left(m/s^{2}\right)$$$.

RESULTS:

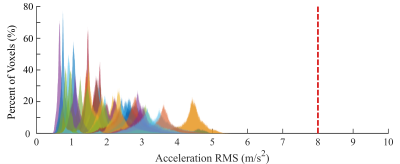

Based on the brain displacement amplitude and equation (2), the acceleration RMS for each pixel is estimated. Colored histograms of acceleration RMS data are presented in figure 2 for each subject. The acceleration RMS of brain tissue for all 45 subjects are less than 8.00 $$$\left(m/s^{2}\right)$$$, the maximum value suggested by the EU 2002 Directive 2002/44/EC. The subject with the largest vibration amplitude, had the median acceleration RMS value of 4.45 $$$\left(m/s^{2}\right)$$$, and the maximum (99th percentile) acceleration RMS value of 5.17 $$$\left(m/s^{2}\right)$$$. Among all subjects, the mean value of the maximum displacement, d, of brain tissue was 20.01 μm, which is much less than the maximum amplitude allowable based on the EU 2002/44/EC guideline for a 60 Hz vibration exposure, which is 140.7 μm.DISCUSSION:

This study measured vibration exposure throughout the brain in vivo ruing typical brain MRE studies, with reference to suggested criteria in the European Parliament adopted Directive 2002/44/EC. The result demonstrated that vibration exposure during a routine MRE brain exam is well below comfort-based exposure limits suggested in the EU 2002/44/EC standard.CONCLUSION:

Typical tissue vibration exposure levels in current brain MRE studies are below the EU 2002/44/EC comfort-based recommendations.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] M. C. Murphy, J. Huston, and R. L. Ehman, “MR elastography of the brain and its application in neurological diseases,” Neuroimage, vol. 187, pp. 176–183, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.008.

[2] P. T. Weavers et al., “Technical Note: Compact three-tesla magnetic resonance imager with high-performance gradients passes ACR image quality and acoustic noise tests,” Med Phys, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 1259–1264, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1118/1.4941362.

[3] T. K. F. Foo et al., “Lightweight, compact, and high-performance 3T MR system for imaging the brain and extremities,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 80, no. 5, pp. 2232–2245, Nov. 2018, doi: 10.1002/MRM.27175.

[4] Z. Yin et al., “In vivo characterization of 3D skull and brain motion during dynamic head vibration using magnetic resonance elastography,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 80, no. 6, 2018, doi: 10.1002/mrm.27347.

[5] E. U. Directive and G. E. Provisions, “Directive 2002/44/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 25 June 2002 on the minimum health and safety requirements regarding the exposure of workers to the risks arising from physical agents (vibration)(sixteenth individual Directive within the meaning of Article 16 (1) of Directive 89/391/EEC),” Official Journal of the European Communities, L, vol. 117, no. 13, pp. 6–7, 2002.