5134

DeepCardioPlanner: Deep Learning-based tool for automatic CMR planning1Institute for Systems and Robotics - Lisboa and Department of Bioengineering, Instituto Superior Técnico - Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 3Centre for Medical Image Science and Visualization (CMIV), Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 4MR Physics, Perspectum Ltd, Oxford, United Kingdom, 5Ultromics Ltd, Oxford, United Kingdom, 6School of Biomedical Engineering Imaging Sciences, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom, 7Centre for Marine Sciences - CCMAR, Faro, Portugal

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, View Planning

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) is a powerful technique which can be used to perform a comprehensive cardiac examination. However, its adoption is often limited to specialised centres, in part due to the need for highly trained operators to perform the complex procedures of determining the 4 standard cardiac planes: 2-, 3-, 4-chamber and short axis views. To automate view planning, a deep learning-based tool (DeepCardioPlanner) has been proposed to regress the view defining vectors from a rapidly acquired 3D image. It successfully takes advantage of multi-objective learning to allow accurate, fast and reproducible view prescriptions without any operator input.Introduction

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) provides a comprehensive cardiac examination, namely by assessing ventricular function, cardiac morphology, vasculature, perfusion, viability, and metabolism.However, CMR requires highly trained operators for determining the standard double-oblique view planes: short axis (SAX), 2-chamber (2CH), 3-chamber (3CH), and 4-chamber (4CH) views. These patient-specific planes are traditionally prescribed through a multistep planning process, requiring several scout scans and manual adjustments, which increase the scan time and workflow complexity.

Tools for automating this planning process have been proposed (e.g., Cardiac Dot1), but still require some user input. Recently, Deep Learning (DL) methods have been proposed to achieve automatic cardiac planning 2,3,4,5. For example, cardiac anatomic landmark regression from 2D images has been used to prescribe the standard CMR view planes with good results 2,4, but it requires extensive manual annotation to build a dataset to train such methods. Manual annotation free methods have also been proposed for computed tomography (CT), but predict each view position and orientation separately 3. A similar approach based on rapidly acquired volumetric images could be applicable to CMR where automated view planning would be even more valuable.

Here, we propose a set of four deep convolutional neural network (CNN) models (DeepCardioPlanner), each trained via a multi-task learning approach, to predict the orientation and position of each cardiac view plane from a rapidly acquired 3D scan. We tested the ability of DeepCardioPlanner to automatically plan the four cardiac views on clinically acquired patient CMR data.

Methods

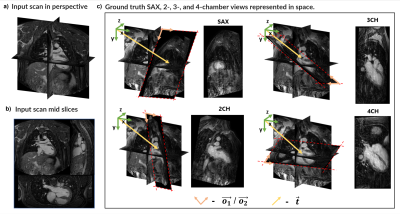

Dataset: The dataset consists of 120 3D CMR (51% with, 49% without contrast) patient scans labelled with the defining vectors of each of the 4 standard CMR view planes (Fig.1c). The datasets were obtained from patients with different pathologies and by different operators. Data was acquired on a 1.5T Philips scanner, using standard clinical protocols and an ECG-triggered volumetric bSSFP sequence with field-of-view=440x440x150 mm3, voxel size=3x3x3mm3, compressed SENSE acceleration factor six, and scan time of 10 seconds (assuming 60 bpm heart rate).Pre-processing: Image intensity was standardised, and the 3D images were resized to 95x95x42 with a 4mm isotropic resolution to reduce computational burden.

Training: To address the plane position and orientation subtasks simultaneously, training was performed by combining two losses. Leveraging knowledge that a plane is defined by a point within it and a normal vector, the plane position loss is set to the Euclidean distance between a predicted point and the plane, and the orientation loss is computed as the cosine similarity between the predicted and ground truth normal vectors. The multi-objective loss used to train the network was the combination of these two losses via an uncertainty based trainable loss weighting approach6.

Regularisation is ensured by weight decay and early stopping. Data augmentation (e.g., additive noise, scaling. translation, rotation) is also used to increase the models’ generalisability.

A stratified 74-13-13 training-validation-test split was used with Adam7 optimizer. Learning rate and augmentation hyperparameters were tuned separately for each view model through a grid search approach.

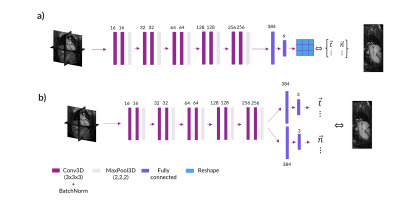

Network Architectures: Two different architectures were compared for the final DeepCardioPlanner tool. Architecture A (NA), similar to Chen et al3, consists of a feature extraction block with five stages of two 3D convolutional layers connected through a batch normalisation operation and followed by a final max pooling layer. The final regression block is used to regress the two vectors that define the given plane (Fig.2a). Architecture B (NB) is the same but with separate regression heads for each subtask (Fig.2b).

Performance Metrics: Performance on the position prediction subtask is assessed by the displacement error (εd), which is the same as position loss, and the orientation subtask is assessed through the angulation error (εθ), which is the angle between predicted and ground truth plane normal vectors.

Results

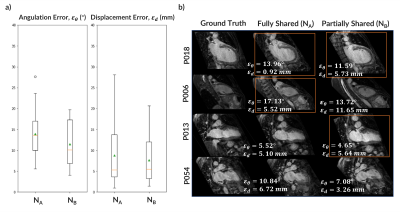

DeepCardioPlanner takes <1sec to prescribe a given view. Even though εd and εθ may appear large, they do not always correspond to a great loss of image plane quality from visual assessment (Fig.3&4).NB yields a better performance in both subtasks for the 2CH view than NA. Sharing parameters from all the layers was constraining the learning process (Fig.3). Hence, the architecture chosen to train all view models was NB.

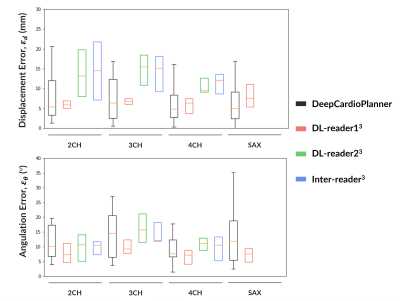

After hyperparameter tuning for each specific view dataset, a model for each view was obtained. Performance metrics are within the literature ranges for the same task with CT and wherein plane orientation and position are predicted separately. Also, DeepCardioPlanner yields test errors at the scale of the inter-operator variability3 (Fig.5).

Conclusion

The proposed DeepCardioPlanner tool successfully takes advantage of multi-objective learning to provide good and fast view prescriptions for all four standard CMR view planes. This automatic method has the potential to greatly reduce examination time and complexity as it is based on 10sec scans and ~1sec prescription time, which may increase efficiency and clinical utility of CMR. Furthermore, DeepCardioPlanner improves upon previous methods by doing this without requiring manually annotated datasets and only needing one model per view. Results can potentially be enhanced through a larger training set with a more refined multi-objective learning approach.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by: NVIDIA GPU hardware grant and utilised NVIDIA RTX 8000 GPU; “la Caixa” Foundation and FCT, I.P. under the project code [LCF/PR/HR22/00533]; FCT through projects UIDB/04326/2020, UIDP/04326/2020, LA/P/0101/2020 and UID/EEA/50009/2020.References

1. Pueyo J., et al., Cardiac Dot Engine: Significant Time Reduction at Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. MAGNETOM Flash 5 (2014).

2. Blansit, K., et al. "Deep Learning–based Prescription of Cardiac MRI Planes". Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 1. 6: e180069 (2019).

3. Chen, Z., et al. "Automated cardiac volume assessment and cardiac long- and short-axis imaging plane prediction from electrocardiogram-gated computed tomography volumes enabled by deep learning". European Heart Journal - Digital Health 2. 2: 311–322 (2021).

4. Le, M., et al. Computationally Efficient Cardiac Views Projection Using 3D Convolutional Neural Networks.", arXiv:1711.01345 (2017)

5. Corrado, P., et al. “Automatic Measurement Plane Placement for 4D Flow MRI of the Great Vessels Using Deep Learning.” International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, Springer Science, 17:1, 199–210 (2022).

6. Cipolla, R., Gal, Y., and Kendall, A., "Multi-task Learning Using Uncertainty to Weigh Losses for Scene Geometry and Semantics," 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 7482-7491 (2018).

7. Diederik P., K., and Ba, J. "Adam: A method for stochastic optimization." arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Figures