5126

Deep Learning Pipeline for Preprocessing and Segmenting Cardiac Magnetic Resonance of Single Ventricle Patients from an Image Registry1Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Cardiology, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

We have created an end-to-end machine learning pipeline that takes cardiac magnetic resonance scans straight from a registry of single ventricle patients, performs image classification, calculates bounding boxes, and segments the ventricles. The clinical utility of the pipeline is that there is very little human preprocessing required from the clinicians. The pipeline has great robustness as it is trained on multicenter data from different countries, with different scanners, image sizes and aspect ratios, patient ages (relating to heart sizes), and the inherent variability of single ventricle patients. Heart metrics calculated from our pipeline can guide treatment for single ventricle patients.Introduction

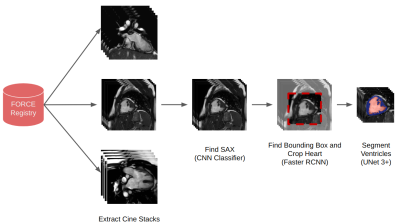

The FORCE registry is the first large-scale multi-centre cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) registry of single ventricle patients who have undergone the Fontan (or similar) procedure. The database contains over 4000 MRI scans from over 2700 patients from hospitals in the US, Canada, and the UK.1 A significant challenge for the registry is core lab processing, particularly for evaluating ventricular volumes.We propose an end-to-end machine learning (ML) pipeline that automatically finds cine stacks, performs classification to determine the orientation, defines a bounding box around the structure of interest, and performs ventricular segmentation of Fontan patients. This type of pipeline would fully automate core lab processing allowing the registry's full potential to be realised. The pipeline schematic is shown in Fig. 1.

This study aims to validate each section of the pipeline and then test the whole pipeline on 100 unsegmented cases.

Methods

Our training dataset consists of 208 single ventricle patients' CMR studies from the FORCE registry. 165 exams were used in training, 13 for validation, and 30 for testing. Experts drew endocardial and epicardial contours in each exam on end-systolic and end-diastolic short-axis CMR images.The first stage of the pipeline takes CMR images straight from the FORCE registry and uses information from the DICOM headers to extract cine stacks.

The second stage of the pipeline uses a convolutional neural network (CNN) classifier to identify short-axis images. The classifier consists of three layers of 2D convolutions (with 32, 32 and 64 filters in each layer) and max-pooling operations followed by a fully connected dense layer (64 units). The output from the final sigmoid is the probability that the image is a short-axis. The classifier was trained with a binary cross-entropy loss on a balanced dataset of 110558 individual CMR images and validated on 8486 images.

During inference with the full pipeline, the middle three slices of a given stack are inputted into the classifier, and the mean probability of being short-axis is calculated. The stack with the highest mean probability is then identified as the short-axis stack.

The third stage of the pipeline uses a Faster R-CNN architecture with a Resnet50 backbone to crop around the heart, with the ground truth bounding boxes being derived from the ground truth epicardial segmentations. The Faster R-CNN consists of a region proposal network and a classifier.2 The region proposal suggests several possible bounding boxes, and the classifier outputs a probability that the object is present. We trained on 1852 samples and validated on 377 samples.

After cropping, the final stage of the pipeline is segmentation which uses the UNet 3+ architecture. The UNet 3+ is a modified UNet model that uses full-scale skip connections.3 A total of 4334 individual CMR images were used for training and 336 for validation. The model outputs three channels providing the voxelwise classification of background, endocardium and myocardium.

Unlike the original UNet 3+, our model used a dice loss, a softmax activation and did not use deep supervision or their “classification-guided module”. At each epoch, data augmentation was introduced to improve the segmentation.

Results

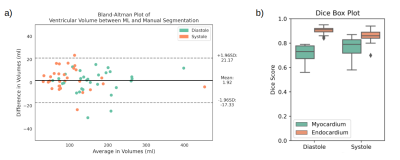

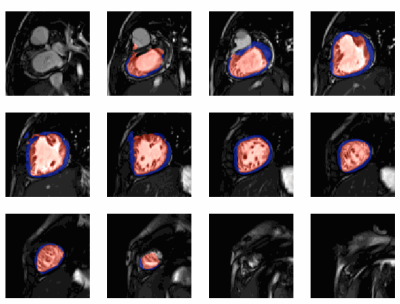

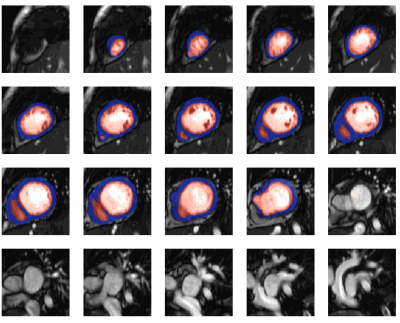

All models were separately validated on the same 30 exams. For short-axis classification, the accuracy was 87%, precision was 82%, recall was 95%, and the F1 score was 88%. The bounding box detection model achieved a mean Intersection over Union (IoU) of 0.56. The UNet 3+ performance on individual images (Dice score) and whole stacks (volumes) are shown in Fig. 2. Fig. 2a shows that the difference in volume between the truth and model prediction is around 20 ml with no bias towards over or under-segmentation. Fig. 2b shows that the average endocardium and myocardium Dice scores were 0.89 and 0.76, respectively.The performance of the whole pipeline was finally evaluated using the data of 100 unseen patients from different hospitals. In 10 patients, the pipeline correctly identified no short-axis stacks. In the remaining 90 patients, the ML classifier correctly identified the short-axis stacks in all patients. In 10 of these patients, the cropping failed, and segmentation was not performed. In the remaining 80 patients, the UNet 3+ performed well, as seen in Fig. 3. The average time to fully process one patient is 45 seconds (including the creation of GIFs for quality assurance).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have created an end-to-end machine learning pipeline that automatically takes CMR scans straight from a registry to extract short-axis cine images, performs cropping and accurately segments the ventricles.This is a challenging problem due to both the heterogeneity of the data from multiple sites and the highly variable anatomy. Nevertheless, we demonstrated that both the ML classifier and segmentation networks worked very well.

The cropping did have a moderate failure rate and does require some further development. Nevertheless, we have shown that it is possible to create a full data pipeline for the FORCE registry that could provide core lab segmentation without any user input. This means that all the patients in the FORCE registry can be segmented over 2700, with only a small portion (208 patients) needing manual segmentation. The pipeline's robustness means new hospitals' scans can automatically be segmented as new patients are recruited.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Additional Ventures and the FORCE registry for providing the cardiac MRI images for research. TY acknowledges support from the UKRI Centre for Doctoral Training in AI-enabled Healthcare studentship (EP/S021612/1).

References

1. Fontan: Force study Fontan outcomes registry using CMR examinations. https://www.forceregistry.org. (Accessed: November 9, 2022).

2. Ren, S. et al. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. 2017. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 39(6), pp. 1137–1149.

3. Huang, H. et al. UNet 3+: A full-scale connected UNet for medical image segmentation, 2020. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP).

Figures