5124

A Data Augmentation Framework to Improve R-peak Detection in ECG Recorded in MRI Scanners1Epsidy, Nancy, France, 2University of Sousse, National School of Engineers, LATIS-Laboratory of Advanced Technology and Intelligent Systems, Sousse, Tunisia, 3IADI, INSERM U1254 and Université de Lorraine, Nancy, France, 4CIC-IT 1433, INSERM, Université de Lorraine and CHRU Nancy, Nancy, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Data Analysis, Machine learning/Artificial intelligence

Detecting R-peaks in ECG using deep learning (DL) requires large, annotated datasets. Such datasets with the MRI-specific magneto-hydrodynamic (MHD) effect, do not exist currently. We propose a robust data augmentation framework using records available online, adding realistic MHD artifacts to augment the training dataset. MHD artifacts were modelled from eight 3T MRI-ECG records, and added to 75 non-MRI-ECG records. The R-peak detection was evaluated on six 3T MRI-ECG records. Compared to a DL model trained without data augmentation, the number of false positives and missed detections were reduced by 57.6% and 16.4%, the overall error was decreased by 25%.INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death and disabilities worldwide [1], for which cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) plays a key role [2]. During CMR, image acquisition is often prospectively synchronized with heartbeats; its quality relies on a fast and reliable detection of R-peaks, which is challenging [3, 4]. MRI-ECG quality is altered by the magneto-hydrodynamic (MHD) effect, which is difficult to suppress compared to gradient switching and radio frequency. Pan-Tompkins is a reference algorithm for R-peak detection on standard ECG signals [5], with deep learning (DL) architectures [6, 7] gaining momentum. However, these approaches fail with MRI-ECG data (Figure 1). We propose a robust data augmentation framework (DAF) to enrich publicly available annotated ECG datasets with realistic MHD artifacts, and demonstrate its efficacy to detect R-peaks through a DL architecture.MATERIALS AND METHODS

DL architectureR-peak detection is approached as a 1D segmentation task using UNet, a DL architecture reputed for its high accuracy and reduced computational complexity. UNet is composed of convolutional layers which are distributed into two symmetric blocks: encoder and decoder. The encoder down-samples the input through six convolutional layers with a down-sampling factor of two, while the decoder up-samples decompresses the feature vector back to its original size with a reverse configuration of the encoder. To guarantee an accurate localization, UNet uses simultaneously global and contextual information through skip connections.

Training on ECG data

INCART [8], a good quality 12 lead non-MRI-ECG database comprising 75 records and over 175,000 beats, was used to train the UNet architecture. Normalized ECG segments of ~4 sec (2,048 samples at 500 Hz) were fed as input. UNet outputs a 1D segmentation map with each R-peak centered in a 40-sample segment. A batch size of 64 and Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 were used. Weights were randomly initialized with the Xavier uniform distribution. Training was stopped early when cross-entropy loss stopped decreasing (patience = 10 epochs). The total number of trainable parameters was 79,409. First, a lead-by-lead training was performed using the eight representative ECG leads (I, II, V1 to V6). Then, a multi-lead training was implemented, converting 12 ECG leads to 3D vectorcardiogram (VCG) [9].

Data augmentation

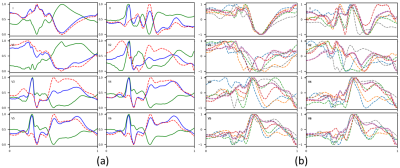

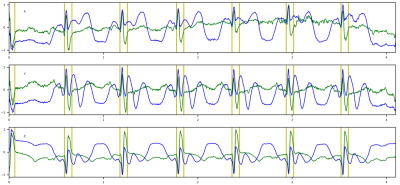

An empirical model of MHD artifacts [10] was built on eight MRI-ECG records [4]. After registering data according to R-peak locations, a median operator was applied to extract MHD artifact templates, one per ECG lead, and per record (Figure 2). To augment the training data, realistic MHD artifact templates were added to the INCART data lead-by-lead, registered at R-peak locations (Figure 3). Training UNet was done without and with 200% data augmentation.

Testing on MRI-ECG data

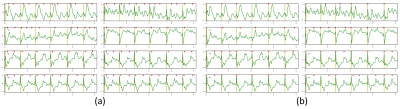

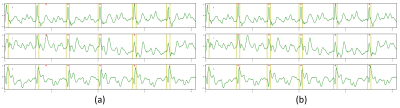

A 12 lead MRI-ECG database at 3T, comprising six records and 4,096 beats, was used for testing [4]. Pan-Tompkins R-peak detector was applied lead-by-lead (Figure 1.a). The trained UNet model was also tested lead-by-lead (Figure 1.b). Two models, trained using 3D VCG data without and with data augmentation, were assessed (Figure 4).

RESULTS

Testing on non-MRI-ECG data (INCART), recall and precision exceeded 99% for both lead-by-lead and VCG approaches. On MRI-ECG data, Pan-Tompkins yielded recall (resp. precision) between 62% and 100% (resp. between 39% and 90%). Results were poor on leads I and II, closest to the CMR clinical leads (Figure 5). V3 and V4, usually not clinically accessible in CMR, had the best recall (V3: 98%, V4: 100%) and precision (V3: 90%, V4: 89%). Without data augmentation, UNet yielded results comparable to Pan-Tompkins: recall (resp. precision) between 55% and 99% (resp. between 61% and 83%). When trained with 3D VCG data, UNet results improved to 84% recall and 89% precision. False positives (FP) were reduced to 465 (~11%), less than the best result from Pan-Tompkins on V3 (509). False negatives (FN) remain at an acceptable value (~17%). With data augmentation, UNet results improved to 86% recall and 96% precision, FP reduced to <5% FP and FN to ~14% (Figure 5). Compared to the training without data augmentation, the number of FP and FN was reduced by 57.6% and 16.4%, and the overall error (1 – F1-score) decreased by 25%.DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

FP and FN originating from MHD artifacts cause image artifacts and decrease acquisition efficiency. The state-of-the-art VCG-based approaches [11, 12] provide reliable R-peak detection at 1.5T but fail at higher field strengths, forcing clinicians to move electrodes or use other techniques, reducing image quality [13]. Our results confirm that VCG improves R-peak detection. DL architectures require MRI-ECG data, which is scarce. The alternative we propose, to use Non-MRI-ECG data with a DAF, allows to improve the prediction accuracy of a DL model, and to reduce the number of FP and FN in R-peak detection. The realistic, empirical measurement of MHD used here could be enhanced by other models [10]. Testing, limited to 3T here, could be adapted to other field strengths using appropriate MHD artifacts templates. We used records from the same subjects with the DAF and for testing. This obvious limitation does not reduce the interest of the methodology. Adding realistic MHD artifacts using a DAF to existing non-MRI-ECG databases is a way to overcome the scarcity of MRI-ECG data.Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Bpifrance program under grant number 0187793/00. PA and JO were supported by a grant from the ERA-CVD Joint Transnational Call 2019, MEIDIC-VTACH (ANR-19-ECVD-0004).References

[1] « Cardiovascular diseases », 03 November 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds)

[2] R. D. Adam, J. Shambrook and A. S. Flett, « The prognostic role of tissue characterisation using cardiovascular magnetic resonance in heart failure », Cardiac Failure Review, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 86-96, 2017.

[3] J. Oster and G. D. Clifford, « Acquisition of electrocardiogram signals during magnetic resonance imaging », Physiological Measurement, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 119-142, 2017.

[4] J. W. Krug, M. Schmidt, G. Rose and M. Friebe, « A database of electrocardiogram signals acquired in different magnetic resonance imaging scanners », Computing in Cardiology - CinC, pp. 1-4, 2017.

[5] J. Pan and W. J. Tompkins, « A real-time QRS detection algorithm », IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 230-236, 1985.

[6] O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer and Thomas Brox, « U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation, Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention - MICCAI, pp. 234-241, 2015.

[7] M. U. Zahid, S. Kiranyaz, T. Ince, O. C. Devecioglu, M. E. H. Chowdhury, A. Khandakar, A. Tahir and M. Gabbouj, « Robust R-Peak detection in low-quality Holter ECGs using 1D convolutional neural network », IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 119-128, 2022.

[8] A. L. Goldberger, L. A. N. Amaral, L. Glass, J. M. Hausdorff, P. C. Ivanov, R. G. Mark, J. E. Mietus, G. B. Moody, C. Peng and H. E. Stanley, « PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals », Circulation, vol. 101, no. 23, pp. 215-220, 2000.

[9] J. A. Kors, G. Vanherpen, A. C. Sittig and J. H. Van Bemmel, « Reconstruction of the Frank vectorcardiogram from standard electrocardiographic leads: diagnostic comparison of different methods », European Heart Journal, vol. 11, pp. 1083-1092, 1990.

[10] J. Oster, R. Llinares, S. Payne, Z. T. H. Tse, E. J. Schmidt and G. D Clifford, « Comparison of three artificial models of the magnetohydrodynamic effect on the electrocardiogram », Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, vol. 18, no. 13, pp. 1400-1417, 2015.

[11] S. E. Fischer, S. A. Wickline and C. H. Lorenz, « Novel real-time R-wave detection algorithm based on the vectorcardiogram for accurate gated magnetic resonance acquisitions », Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 361-370, 1999.

[12] J. M. Chia, S. E. Fischer, S. A. Wickline and C. H. Lorenz, « Performance of QRS detection for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with a novel vectorcardiographic triggering method », vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 678-88, 2000.

[13] S. Man, A. C. Maan, M. J. Schalij, C. A. Swenne, « Vectorcardiographic diagnostic & prognostic information derived from the 12‐lead electrocardiogram: historical review and clinical perspective », Journal of Electrocardiology, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 463-475, 2015.

Figures

Figure 1. Visual lead-by-lead results of R-peak detections on one record example of the 3T MRI-ECG database. (a) Pan-Tompkins algorithm. (b) UNet architecture.

green = ECG data; yellow bars = annotated R-peaks; red triangles = detected R-peaks.

Figure 4. R-peak detection results on the 3T MRI-ECG database showing VCG components (X, Y, Z). (a) Without DAF. (b) With DAF.

yellow bars = annotated R-peaks; red triangles = detected R-peaks.

Figure 5. Testing of the Pan-Tompkins algorithm and the trained UNet model, with and without Data Augmentation Framework (DAF) on the 3T MRI-ECG database.

FP = false positives; FN = false negatives.