5122

Validation of open-source minimal TE sequences across three independent sites

Gehua Tong1, Andreia S. Gaspar2, Rita G. Nunes2, Jon-Fredrik Nielsen3, John Thomas Vaughan, Jr.1,4, and Sairam Geethanath4,5

1Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 2Institute for Systems and Robotics (ISR-Lisboa)/LaRSyS, Department of Bioengineering, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 3Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 4Columbia Magnetic Resonance Research Center, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 5Accessible MR Laboratory, BioMedical Engineering and Imaging Institute, Dept. of Diagnostic, Molecular and Interventional Radiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, New York, NY, United States

1Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 2Institute for Systems and Robotics (ISR-Lisboa)/LaRSyS, Department of Bioengineering, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 3Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 4Columbia Magnetic Resonance Research Center, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 5Accessible MR Laboratory, BioMedical Engineering and Imaging Institute, Dept. of Diagnostic, Molecular and Interventional Radiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Validation, Pulse Sequence Design

We validated five open-source PyPulseq minimal TE sequences (half/full pulse 2D/3D UTEs and COncurrent Dephasing and Excitation (CODE)) at three sites with different scanner models. The ISMRM/NIST T2 array and a porcine muscle and bone sample were imaged. SNR, contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), and T2 contrast curves were calculated and compared. We found that the sequences were able to recover more SNR from bone tissue compared to vendor GRE (an additional 50% - 1060% for 3T and 34% - 474% for 1.5T) and higher signal for short-T2 spheres but intersite differences existed that were consistent with field strengths.Introduction

Open-source pulse sequences provide an accessible way of testing sequences across sites (1–7). These multi-vendor sequence files enable reproducible research where sequences can reduce inter-site variability and be shared to minimize setup time (8). Multisite testing is required for standardizing protocols with biomarkers (9). One example needing reproducibility tests are T2* contrast Ultra-short Echo Time (UTE) sequences in musculoskeletal imaging (10,11). This work assesses inter-site variability of UTE sequences and evaluates the benefits and challenges of open-source standards in contributing to reproducibility research. To this end, five PyPulseq-implemented ultra-short TE sequences were tested across three sites in vitro and ex vivo and compared in terms of SNR, T2* contrast, and ex vivo CNR.Methods

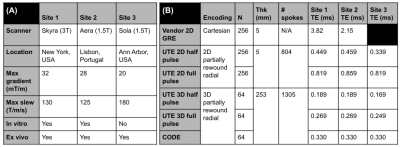

Five minTE sequences (full/half pulse 2D/3D radial UTE and CODE) from a previously described repository (12) were tested at three sites. Site information is included in Figure 1(A). Sequences were communicated as Python functions and .seq files were generated using PyPulseq (3) and tested by three researchers independently. A 2D vendor GRE sequence was chosen as reference and the parameters were matched except for Echo Time (TE) where the lowest value was selected. The in vitro experiments imaged the T2 array of the ISMRM/NIST phantom (13) at Sites 1 and 2; in the ex vivo experiments, similar-sized porcine muscle and bone samples 150-200 mm wide were acquired at all three sites. Sequence parameters were equalized except for TEs which were chosen to be the minimum value under each site’s hardware constraints (Figure 1(B)). Reconstruction was performed using PyNUFFT (14) for the radial k-space followed by sum-of-squares channel combination.Image quality metrics were computed for between-site comparison. For the T2 array, circular Regions-of-Interest (ROIs) were selected for SNR measurements against background noise, and mean ROI signals were plotted against standard T2 values at the respective field strengths. In addition, SNRs were calculated for the main cylinder content (arrow on Figure 2) and for Sphere 14 which has the lowest T2 values. For the ex vivo data, bone SNR, muscle SNR, bone-muscle CNR and bone/muscle signal ratio were measured using manually selected ROIs.

Results and Discussion

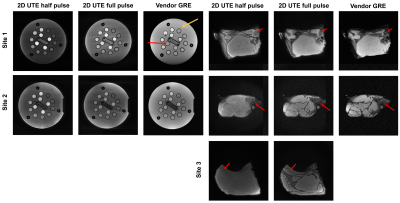

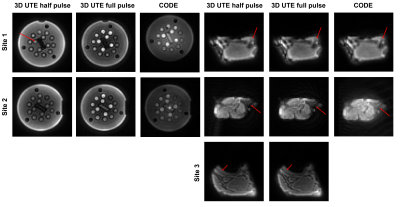

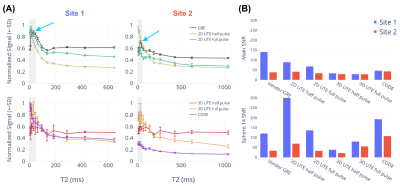

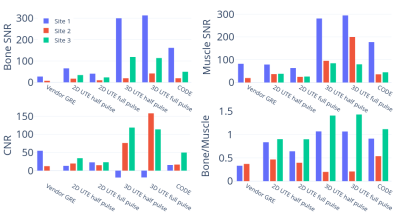

On the T2 array, similar relative contrasts across the 14 spheres were achieved between Site 1 and Site 2 (Figure 2, 4). Signal was recovered best from spheres with the lowest T2 and decreased for spheres with longer T2 (Figure 4 (A)). We attribute this to a potential proton density effect that shows itself at TEs much lower than the lowest T2 at 7.8 ms (1.5T) and 5.35 ms (3T) for Sphere 14. The GRE sequence supports this hypothesis as a reversal of signal trend around Sphere 11-12 is seen (Figure 4, blue arrows) at both sites at the longer TE of 2 - 4 ms, about half of the T2 value of Sphere 14. At Site 1, the main cylinder SNR was reduced in the UTE sequences while it was higher in Sphere 14 thanks to the reduced decay of the short T2 signal. Notably, Site 2 had to include an additional spherical phantom next to the porcine sample to achieve the required scanner load which caused more background noise.On the ex vivo sample, similar contrast between bone, muscle, and connective tissue was seen across sites with the best visual contrast seen in the 2D UTE full pulse sequence. Bone SNR was overall increased compared to the vendor GRE sequence with a larger effect on the 3D sequences at Site 1 with the higher 3T field strength (Figure 5). Bone-muscle signal ratios were increased for the 2D sequences and more variable in 3D sequences which we attribute to the lower resolution that causes more partial-volume effects. The effect also caused negative CNR values in 3D sequences at Site 1, which has a small bone ROI. The 2D half pulse sequences showed less contrast and more edge related artifacts that could have been caused, respectively, by a reduction in TE and slice profile sidebands in the half-pulse method which show up more obviously in ex vivo samples than a phantom that changes little in the slice direction.

Several factors could be further equalized: choosing more uniform ex vivo samples or using a traveling sample/human subject, fixing echo times, and ensuring coil setups that work on all scanners. Better planned positioning and registration procedures would enable image similarity measures such as PSNR and SSIM, and multiple experiments over time could help assess repeatability. Lastly, we note that the three scanners were manufactured by the same vendor. Vendor-specific interpreters often need adaptation to use newer versions of the open-source sequence format and harmonizing software packages is key for testing across vendors (15).

Conclusion

Five open-source minimal TE sequences were tested across three independent sites. The TEs achieved ranged from 169 to 330 microseconds for 3D sequences and 339 to 859 microseconds for 2D sequences. Bone SNR was found to be consistently higher than in reference vendor GRE sequences (TE = 3.82 and 2.15 ms) in ex vivo Porcine samples and high signal was recovered from the shortest-T2 spheres on the ISMRM/NIST T2 array. Sequence scripts in PyPulseq with tested system parameters were shared in a public repository (16).Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia grant UID/EEA/50009/2020, the NIH grant U24NS120056, and the NIH grant 1U01 EB025153-01 and performed at the Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute and the Columbia MR Research Center. The authors would like to thank Enlin Qian for his MATLAB code that performs automated ISMRM/NIST phantom ROI analysis.References

1. Layton KJ, Kroboth S, Jia F, et al. Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017;77:1544–1552 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26235.2. Ravi KS, Potdar S, Poojar P, et al. Pulseq-Graphical Programming Interface: Open source visual environment for prototyping pulse sequences and integrated magnetic resonance imaging algorithm development. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2018;52:9–15 doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2018.03.008.

3. Ravi K, Geethanath S, Vaughan J. PyPulseq: A Python Package for MRI Pulse Sequence Design. J. Open Source Softw. 2019;4:1725 doi: 10.21105/joss.01725.

4. Nielsen J-F, Noll DC. TOPPE: A framework for rapid prototyping of MR pulse sequences. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018;79:3128–3134 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26990.

5. Stöcker T, Vahedipour K, Pflugfelder D, Shah NJ. High-performance computing MRI simulations. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010;64:186–193 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22406.

6. Jochimsen TH, von Mengershausen M. ODIN—Object-oriented Development Interface for NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2004;170:67–78 doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.05.021.

7. Tong G, Gaspar AS, Qian E, et al. A framework for validating open-source pulse sequences. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2022;87:7–18 doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2021.11.014.

8. Herz K, Mueller S, Perlman O, et al. Pulseq-CEST: Towards multi-site multi-vendor compatibility and reproducibility of CEST experiments using an open-source sequence standard. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;86:1845–1858 doi: 10.1002/mrm.28825.

9. Schwartz DL, Tagge I, Powers K, et al. Multisite reliability and repeatability of an advanced brain MRI protocol. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019;50:878–888 doi: 10.1002/jmri.26652.

10. Ahlawat S, Fritz J, Morris CD, Fayad LM. Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers in musculoskeletal soft tissue tumors: Review of conventional features and focus on nonmorphologic imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019;50:11–27 doi: 10.1002/jmri.26659.

11. Chang EY, Du J, Chung CB. UTE imaging in the musculoskeletal system. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015;41:870–883 doi: 10.1002/jmri.24713.

12. Tong G, Vaughan JT, Geethanath S. An open-source repository of minimum echo time sequences. In: Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Vol. 2022.

13. Stupic KF, Ainslie M, Boss MA, et al. A standard system phantom for magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;86:1194–1211 doi: 10.1002/mrm.28779.

14. Lin J-M. Python Non-Uniform Fast Fourier Transform (PyNUFFT): An Accelerated Non-Cartesian MRI Package on a Heterogeneous Platform (CPU/GPU). J. Imaging 2018;4:51 doi: 10.3390/jimaging4030051.

15. Clarke WT, Mougin O, Driver ID, et al. Multi-site harmonization of 7 tesla MRI neuroimaging protocols. NeuroImage 2020;206:116335 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116335.

16. imr-framework. Open-Source Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Minimal Echo Time. 2022. https://github.com/imr-framework/minTE. Accessed November 9th, 2022.

Figures

Figure 1: (A) Site information and (B) Experiments list for multi-site testing of open-source UTE sequences. Shared parameters include: FOV = 253 mm (both 2D and 3D), TR = 15 ms, FA = 10 deg.

Figure 2: 2D UTE images compared to minimum-TE vendor-supplied GRE of the NIST T2 array (left) and ex vivo porcine sample (right). The yellow arrow indicates the main cylinder body where an ROI was chosen to calculate the main SNR value. The ex vivo images were cropped to emphasize details. Red arrows indicate the shortest-T2 components.

Figure 3: 3D UTE and CODE images of the NIST T2 array (left) and ex vivo porcine sample (right). Since the image targets are plane-like, only the relevant slice was selected. The ex vivo images were cropped to emphasize details. Red arrows indicate the shortest-T2 components.

Figure 4: In vitro (ISMRM/NIST T2 array) image quality. (A) Average signal with standard deviation error bars for the 14 spheres plotted against their standard T2 values. Gray shading indicates the lowest T2s (< 50 ms) and blue arrows show where the signal trend reverses in vendor GRE; (B) SNR of main cylinder and Sphere 14 for each of the sequences tested between Sites 1 and 2.

Figure 5: Ex vivo image metrics. SNR values were calculated as mean ROI signals divided by background ROI standard deviations and CNR values as (muscle - bone) / (background standard deviation). The bone/muscle signal ratio was also calculated to evaluate shifts in contrast. Negative CNR values seen in Site 1 3D UTE are attributed to the small bone ROI and partial volume effects.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5122