5105

Motion Corrected Multi-scale Low Rank Reconstructions for Highly Accelerated 3D Dynamic Acquisitions1University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Motion Correction

This work develops a method for large-scale motion compensated 4D reconstructions of fully 3D radial acquisitions at near 1mm isotropic spatial resolution and sub-second temporal resolution. We combine and extend multi-scale image reconstruction (Extreme MRI) with k-space based motion field estimation (MOTUS) to solve for a multi-scale low rank representations of both images and motion fields. This combined approach outperforms the multi-scale low rank reconstruction without motion fields.Introduction

Significant progress has been made in the development of non-Cartesian acquisitions that permit dynamic, volumetric imaging. These acquisitions allow for fast, free breathing scans that improve patient comfort. Further, these acquisitions permit flexible data rebinning1 allowing for reconstructions along multiple dimensions to resolve respiratory and/or cardiac phases. Motion correction applied to these phase-resolved reconstructions often leads to better image quality as it improves use of available data across motion states. However, phase-resolved reconstructions are often limited by intra-frame motion artifact due to bulk motion and irregular respirations.One approach to solve this problem is to reconstruct images at sufficient temporal resolution to capture these transient dynamics. This has recently been realized with the Extreme MRI approach2, that directly optimizes a highly compressed multi-scale low rank representation (MSLR)2,3 of the 4D time series. Although Extreme MRI does recover these transient dynamics, image quality is often degraded when bulk or irregular motion occurs.

This work aims to extend motion correction to Extreme MRI. We assume that like a time series of images, a time series of motion fields is also highly compressible4. Following that assumption, we solve directly for a memory efficient multi-scale low rank representation of the motion fields using a MOTUS4-like approach and subsequently incorporate this compressed motion field representation into Extreme MRI. We apply this motion compensated multi-scale low rank (MoCo-MSLR) approach to time-resolved lung imaging acquired with fully 3D radial trajectories during free breathing and directly compare to Extreme MRI.

Methods

MoCo-MSLR is a two-stage method that consists of $$$\textbf{(1)}$$$ solving for the MSLR motion field representation in k-space using a loss between a warped template image and acquired k-space data and $$$\textbf{(2)}$$$ motion corrected Extreme MRI. Note all objective functions listed below are updated stochastically by randomly selecting a frame $$$t \in \{t_1,t_2,...,T\}$$$.1.Multi-scale low rank motion field estimation

If motion is the only source of dynamics in a time series than the relationship between a template image $$$I_{temp}$$$ and acquired k-space data $$$Y$$$ can be represented entirely through the warps applied to the template image:

$$Y=\mathcal{A}(I_{temp}(\Omega))$$ Where $$$\mathcal{A}$$$ is multi-channel sensing operator, and $$$\Omega$$$ is the motion field time series.

For the inverse formulation, in place of solving for $$$\Omega$$$ we solve directly for $$$\Phi$$$ representing the multi-scale motion field spatial basis and $$$\Psi$$$ representing the multi-scale motion field temporal basis to both regularize the problem and reduce memory consumption. To further regularize the problem, motion fields are smoothed spatially using total variation to allow for accurate modeling of sliding motion. The variational form of the nuclear norm is used to prevent modeling of noise at high temporal resolution. Noise modeling leads to high frequency temporal oscillations in the image. The objective function to solve for the compressed motion field representation for a randomly selected frame at time t then is: $$F(\Phi,\Psi_{t})=||Y_t-\mathcal{A}(I_{temp}(\Omega_t))||^2+\lambda(||\Phi||^2+||D\Psi_t||^2)+\gamma||\nabla\Omega_t|| $$ Where $$$\lambda$$$ and $$$\gamma$$$ are regularization weights, $$$D$$$ is the temporal difference operator,$$$\nabla$$$ computes spatial gradients. Note that $$$\Omega_t=f(\Phi,\Psi_{t})$$$ where $$$f$$$ is an operator that converts MSLR bases to frames

2.Motion-Compensated Extreme MRI

The original Extreme MRI approach minimizes the following objective function:

$$F(L,R_t)=||Y_t-\mathcal{A}(L,R_t)||^2+\lambda(||L||^2+||R_t||^2)$$ Where $$$L$$$ is the MSLR spatial basis and $$$R_t$$$ is the MSLR temporal basis at time t.

To incorporate motion compensation into the Extreme MRI objective function, we apply the warp $$$\Omega_t=f(\Phi,\Psi_t)$$$ to the frame $$$I_t=f(L,R_t)$$$ and incorporate that warped frame into the data-consistency term. Assuming perfect registration, $$$I_t$$$ should be aligned with all other frames improving the conditioning of the Extreme MRI model. This leads to the following objective function:

$$F(L,R_t)=||Y_t-\mathcal{A}(I_t(\Omega_t))||^2+\lambda(||L||^2+||R_t||^2)$$

Experiments

MoCo-MSLR was applied to free breathing fully 3D radial lung data in a healthy volunteer, a patient with cystic fibrosis and a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Reconstructions at ~500ms temporal resolution and 1.25mm spatial resolution were run to resolve respiratory motion. For the motion field estimation step, the template image was reconstructed using conjugate gradient descent using all acquired k-space projections binned together. Spatial motion field bases were initialized using gaussian noise, temporal motion field bases were initialized using all 0s. Autodifferentiation in pytorch was used to update the spatial and temporal motion field bases. The Extreme MRI code at https://github.com/mikgroup/extreme_mri was modified to allow for motion compensation. The final motion compensated reconstruction was run in cupy. All reconstructions were run on one A100 GPU.Results

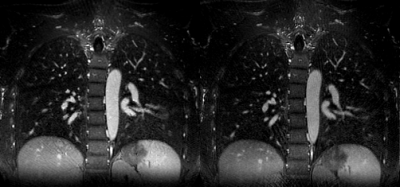

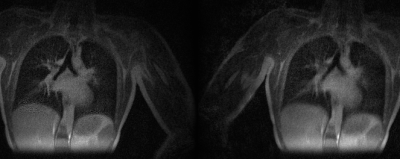

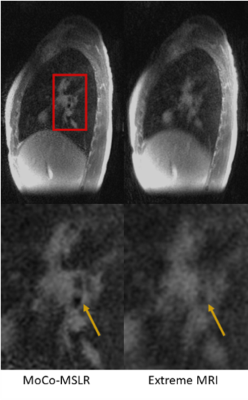

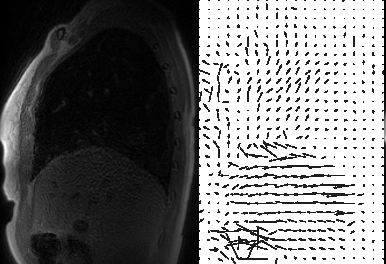

Figures 2 and 3 compare MoCo-MSLR against Extreme MRI for the healthy volunteer with near periodic respiration (Figure 2) vs. the patient with cystic fibrosis with both bulk motion and irregular respiration (Figure 3). Although the two methods perform similarly for the healthy volunteer with near-periodic respiration, MoCo-MSLR better resolves both the liver edge and broncho-vascular structures for the cystic fibrosis patient. This can be seen in both the GIF video (Figure 3) and the static sagittal slice (figure 4). Figure 5 demonstrates both a sagittal slice and its motion field through time from a MoCo-MSLR reconstruction of the patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.Conclusion

MoCo-MSLR allows for motion compensation to be incorporated into large scale time-resolved image reconstruction. We demonstrate improved reconstruction quality over Extreme MRI, especially for scans with transient dynamics.Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge research support from NIH R01 HL136964, NIH R01 CA190298, Medical Scientist Training Program grant: T32 GM140935 and GE HealthcareReferences

1. Feng, Li, et al. "XD‐GRASP: golden‐angle radial MRI with reconstruction of extra motion‐state dimensions using compressed sensing." Magnetic resonance in medicine 75.2 (2016): 775-788.

2.Ong, Frank, et al. "Extreme MRI: Large‐scale volumetric dynamic imaging from continuous non‐gated acquisitions." Magnetic resonance in medicine 84.4 (2020): 1763-1780.2.

3.Ong, Frank, and Michael Lustig. "Beyond low rank+ sparse: Multiscale low rank matrix decomposition." IEEE journal of selected topics in signal processing 10.4 (2016): 672-687.3.

4.Huttinga, Niek RF, et al. "Nonrigid 3D motion estimation at high temporal resolution from prospectively undersampled k‐space data using low‐rank MR‐MOTUS." Magnetic resonance in medicine 85.4 (2021): 2309-2326.

Figures