5048

Functional Connectivity and Clinical Characteristics in Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome1NMR, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany, 2Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, fMRI (resting state), Functional Connectivity, Tourette Syndrome

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) is characterized by the expression of tics and frequently co-occurs with comorbidities including obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), depression, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). For a better discrimination of GTS’ manifestation in brain networks, we analyzed resting-state fMRI data from patients with “GTS only” (no comorbidities) and “GTS plus” (with comorbidities) based on clinical ratings. Our findings suggest that increased intrinsic connectivity of insular cortex with putamen are causally related to GTS while decreased connectivity of the frontal pole, medial temporal and superior frontal gyrus is likely to be related to comorbidities.Introduction.

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) is a neuropsychiatric movement disorder with childhood onset characterized by motor and phonic tics1. Brain imaging studies attempting to identify related networks have produced an inconclusive diversity of findings. A problem of such investigations is that most patients with GTS (90%)30 in addition suffer from comorbidities, such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and depression. We address this issue by analyzing functional connectivity of a GTS cohort composed by patients without (“only”) and with (plus”) comorbidities compared to a cohort of healthy controls.Methods

34 GTS patients, separated into “GTS only” (n=14) and “GTS plus” (n=20) with at least one of the conditions depression, ADHD and OCD and 35 age and sex-matched controls were included after exclusion of 4 patients due to motion artefacts. Resting-state fMRI data were acquired at 3T (MAGNETOM Verio, Siemens Healthineers) with multiband EPI (TR 1.4s, TE 30 ms, flip angle 69°, 2.92mm nominal isotropic resolution, 422 volumes).The CONN toolbox2 was used for preprocessing and analysis of functional connectivity including subject motion estimation and correction, slice-time correction, ART-based outlier detection for scrubbing, segmentation, MNI normalization, and smoothing with an 8mm FWHM Gaussian kernel. Subjects were excluded from the final analysis if 10% of their volumes had framewise displacements exceeding 2mm. The CompCor algorithm was used to regress out physiological fluctuations in gray matter areas.Intrinsic connectivity was then computed comparing (i) “GTS” (all patients), “GTS plus”, and “GTS only” with controls. Briefly, intrinsic connectivity maps represent a measure of node centrality at each voxel, characterized by the strength of connectivity between a given voxel and the rest of the brain3. (ii) From main clusters identified by connectivity analysis in step 1, we further ran seed-based correlation analyses comparing all GTS patients to controls. All analyses included age and sex as covariates and were FWE-corrected (cluster level) with significance level p<0.05.Results

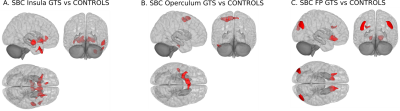

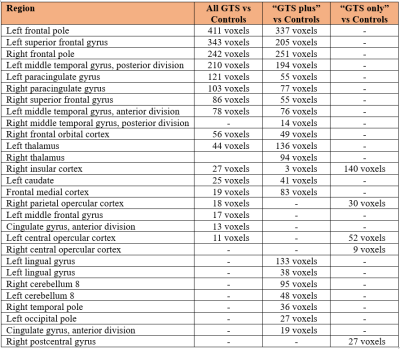

Comparing all patients with controls, we found widespread increased and decreased centrality patterns including hyper-connectivity clusters in the insula, caudate, operculum, thalamus and anterior cingulate gyrus; hypo-connectivity clusters in the frontal pole, superior frontal gyrus, medial frontal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus (Figure 1A). When only including “GTS plus” patients in the comparison, the pattern was largely replicated with subtle differences, like emergence of increased centrality also in the occipital lobe and cerebellum (Figure 1B). However, a striking difference was obtained when including only patients without comorbidities (“GTS only”), yielding hyper-connectivity only in the insula and central opercular cortex (Figure 1C). More detailed results in individual brain regions and cluster sizes are summarized in Table 1. Secondary analyses using these regions as seeds revealed increased connectivity of the insula with putamen, right temporal pole, middle superior and temporal gyrus (Figure 2A), increased connectivity of operculum with superior frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus (Figure 2B), and increased connectivity of the frontal pole with occipital cortex, putamen, nucleus accumbens, and medial frontal gyrus (Figure 2C).Discussion

Our results suggest that an increased node centrality in the right insula and left operculum are mainly reflecting the condition of GTS based on the comparison including only patients without comorbidities (“GTS only”). In healthy individuals, the insula has been related to perception and suppression of bodily feelings4 whereas, in coordination to the insula, the operculum operates by integrating the brain’s sensorial input and the motor output5. Therefore, the observed hyper-connectivity pattern may suggest alterations in circuits where amplification of bodily sensation perception parallels with attempts to suppress a tic. Furthermore, increased connectivity of bilateral putamen to insula, detected when we used the latter as a seed, corroborates earlier suggestions of a network for tic generation comprised by insula, putamen, thalamus and anterior cingulate cortex.6,7,8,9,10 Increased connectivity of the operculum with the superior and the medial frontal gyrus, which are related to self judgement,11,12,13 together with connectivity to the right temporal pole, which has been linked to processing of social emotions,17 may reflect an immediate reaction to the urge and culmination of tics.14,15,16 Decreased connectivity of the medial temporal gyrus18,19 and frontal pole20,21 do not seem to be a specific characteristic of “GTS only” but rather result from comorbid conditions, such as depression, which was most frequently present in our cohort. This assumption seems to be corroborated by the seed-based results: Decreased occipital connectivity has been observed in OCD,22,23 ADHD24,25 and depression,26,27,28,29 which seems to reflect the inverse correlation with the frontal pole observed here.Conclusion

In our cohort, GTS was characterized by a consistent hyper-connectivity pattern of the insula and operculum together with increased connectivity between insula, striatum, and between central operculum and superior ad medial frontal gyrus. This pattern was observed both in GTS patients with and without comorbidities. Conversely, a decrease in connectivity at the frontal pole, superior frontal gyrus and medial temporal gyrus and inverse connectivity pattern between frontal pole and occipital cortex may likely originate from comorbidities.Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Marie Curie ITN TS-EUROTRAIN (FP7-PEOPLE-2012-ITN, Grant No. 316978) and partly by the Helmholtz Alliance “ICEMED–Imaging and Curing Environmental Metabolic Diseases”. We thank Ahmad Seif Kanaan for data acquisition and Sarah Gerasch for clinical assessments.References

1. Jackson, G. M., Draper, A., Dyke, K., Pépés, S. E., & Jackson, S. R. (2015). Inhibition, disinhibition, and the control of action in Tourette syndrome. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19(11), 655-665.

2.Nieto-Castanon, A. (2020). Handbook of Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods in CONN. Hilbert Press.

3. Martuzzi, R., Ramani, R., Qiu, M., Shen, X., Papademetris, X., & Constable, R. T. (2011). A whole-brain voxel based measure of intrinsic connectivity contrast reveals local changes in tissue connectivity with anesthetic without a priori assumptions on thresholds or regions of interest. NeuroImage 58(4), 1044-1050.

4. Craig, A. D. (2011). Significance of the insula for the evolution of human awareness of feelings from the body. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1225(1), 72-82.

5. Mălîia, M. D., Donos, C., Barborica, A., Popa, I., Ciurea, J., Cinatti, S., & Mîndruţă, I. (2018). Functional mapping and effective connectivity of the human operculum. Cortex 109, 303-321.

6. Bohlhalter, S., Goldfine, A., Matteson, S. et al. (2006). Neural correlates of tic generation in Tourette syndrome: an event-related functional MRI study. Brain 129(8), 2029-2037.

7. Neuner, I., Werner, C. J., Arrubla, J. et al. (2014). Imaging the where and when of tic generation and resting state networks in adult Tourette patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 362.

8. Tinaz, S., Malone, P., Hallett, M., & Horovitz, S. G. (2015). Role of the right dorsal anterior insula in the urge to tic in Tourette syndrome. Movement Dis. 30(9), 1190-1197.

9. Rae, C. L., Critchley, H. D., & Seth, A. K. (2019). A Bayesian account of the sensory-motor interactions underlying symptoms of Tourette syndrome. Front. Psychiatry 10, 29.

10. Ganos, C., Al-Fatly, B., Fischer, J. F. et al. (2022). A neural network for tics: insights from causal brain lesions and deep brain stimulation. Brain. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac009.

11. Goldberg, I. I., Harel, M., & Malach, R. (2006). When the brain loses its self: prefrontal inactivation during sensorimotor processing. Neuron 50(2), 329-339.

12. Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Fan, J., & Han, S. (2007). Neural basis of cultural influence on self-representation. NeuroImage 34(3), 1310-1316.

13. Chiao, J. Y., Harada, T., Komeda, H. et al. (2009). Neural basis of individualistic and collectivistic views of self. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30(9), 2813-2820.

14. Ganos, C., Kahl, U., Schunke, O. et al. (2012). Are premonitory urges a prerequisite of tic inhibition in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 83(10), 975-978.

15. Delorme, C., Salvador, A., Voon, V., Roze, E., Vidailhet, M., Hartmann, A., & Worbe, Y. (2016). Illusion of agency in patients with Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome. Cortex 77, 132-140.

16. Langelage, J., Verrel, J., Friedrich, J. et al. (2022). Urge-tic associations in children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1-11.

17. Nakamura, K., Kawashima, R., Sugiura, M. et al. (2001). Neural substrates for recognition of familiar voices: A PET study. Neuropsychologia 39(10), 1047-1054.

18. Fu, C., Zhang, H., Xuan, A., Gao, Y., Xu, J., & Shi, D. (2018). A combined study of 18F‑FDG PET‑CT and fMRI for assessing resting cerebral function in patients with major depressive disorder. Exp. Ther. Med. 16(3), 1873-1881.

19. Karim, H. T., Andreescu, C., Tudorascu, D. et al. (2017). Intrinsic functional connectivity in late-life depression: trajectories over the course of pharmacotherapy in remitters and non-remitters. Mol. Psychiatry 22(3), 450-457.

20. Vasic, N., Walter, H., Sambataro, F., & Wolf, R. C. (2009). Aberrant functional connectivity of dorsolateral prefrontal and cingulate networks in patients with major depression during working memory processing. Psychol. Med. 39(6), 977-987.

21. Veer, I. M., Beckmann, C. F., Van Tol, M. J. et al. (2010). Whole brain resting-state analysis reveals decreased functional connectivity in major depression. Front. Systems Neurosci. 4, 41.

22. Schlösser, R. G., Wagner, G., Schachtzabel, C., Peikert, G., Koch, K., Reichenbach, J. R., & Sauer, H. (2010). Fronto‐cingulate effective connectivity in obsessive compulsive disorder: A study with fMRI and dynamic causal modeling. Hum. Brain Mapp. 31(12), 1834-1850.

23. Bu, X., Hu, X., Zhang, L. et al. (2019). Investigating the predictive value of different resting-state functional MRI parameters in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Translational Psychiatry 9(1), 1-10.

24. Sokunbi, M. O., Fung, W., Sawlani, V., Choppin, S., Linden, D. E., & Thome, J. (2013). Resting state fMRI entropy probes complexity of brain activity in adults with ADHD. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 214(3), 341-348.

25. Qian, A., Wang, X., Liu, H. et al. (2018). Dopamine D4 receptor gene associated with the frontal-striatal-cerebellar loop in children with ADHD: A resting-state fMRI study. Neurosci. Bull. 34(3), 497-506.

26. Townsend, J. D., Eberhart, N. K., Bookheimer, S. Y. et al. (2010). fMRI activation in the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex in unmedicated subjects with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 183(3), 209-217.

27. Peng, D. H., Jiang, K. D., Fang, Y. R. et al. (2011). Decreased regional homogeneity in major depression as revealed by resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Chin. Med. J. 124(03), 369-373.

28. Li, J., Xu, C., Cao, X. et al. (2013). Abnormal activation of the occipital lobes during emotion picture processing in major depressive disorder patients. Neural Regen. Res. 8(18), 1693.

29. Zhong, X., Pu, W., & Yao, S. (2016). Functional alterations of fronto-limbic circuit and default mode network systems in first-episode, drug-naïve patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state fMRI data. J. Affect. Disord. 206, 280-286.

30. Robertson, M. M. (2006). Mood disorders and Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome: an update on prevalence, etiology, comorbidity, clinical associations, and implications. J. Psychosom. Res. 61(3), 349-358.

Figures