5045

Mapping altered cortical microstructural maturation with diffusion kurtosis imaging in children with autism1Department of Radiology, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Phildaelphia, PA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 3Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Gray Matter, Diffusion/Other Diffusion Imaging Techniques

The cellular and molecular processes inside the cerebral cortex play a critical role in typical brain development and neuropsychiatric disorders. Altered cytoarchitecture across brain regions in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was found with histology. Here, we noninvasively mapped the whole-brain cortical cytoarchitectural maturation in 52 children aged 6-9 years with ASD and 59 age-matched typically developmental (TD) children with diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI). Significant cortical mean kurtosis increases in the temporal and frontal regions were found in TD children with almost flat mean kurtosis changes in ASD observed, suggesting altered underlying cortical cytoarchitectural maturation in ASD.Introduction

The cellular and molecular processes inside the human cerebral cortex play a critical role in normal brain development and neuropsychiatric disorders1, 2. Histological studies have found abnormalities in synaptic pruning and neuron density in the brains of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)3-5. However, these studies were limited to discrete brain regions. Quantifying cortical microstructural changes across the entire cerebral cortex could offer important insight into the neuropathology of ASD. Diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) has enabled noninvasive whole-brain microstructural mapping. DKI revealed differential cortical microstructural maturation across brain regions in early brain development6. Here, we aimed to map the altered regional cortical cytoarchitectural maturation of the brains in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) aged 6-9 years with cortical cytoarchitectural maturation of age-matched typically developing (TD) children as the reference. Multi-shell diffusion MRI was acquired to measure mean kurtosis (MK) derived from DKI. To alleviate partial volume effects, MK was extracted at the core of the cerebral cortical ribbon of parcellated brain regions.Methods

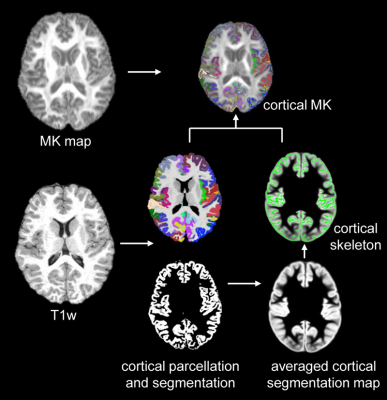

Subjects and data acquisition: 52 children with ASD and 59 TD children aged 6-9 years participated in this study7. The diagnosis of autism was made according to DSM-58. All MR scans were performed on a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner. T1-weighted images (T1w) were acquired with isotropic 0.8mm. High-resolution multi-shell diffusion MR (dMRI) were acquired using multi-band EPI sequences with phase encoding directions of anterior-posterior and posterior-anterior. The dMRI parameters were: TR/TE=3222/89.2ms, FOV=210x210mm2, in plane resolution=1.5x1.5mm2, slice thickness=1.5mm without slice gap, slice number=92, b-values of 1500 and 3000 s/mm2 with 46 non-identical diffusion gradient directions in each shell. Fitting of diffusion kurtosis: dMRI data underwent head-motion, eddy-current and EPI distortion corrections in FSL (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) following the HCP preprocessing pipeline9. MK maps were fitted with corrected dMRI data using Dipy package (https://dipy.org). Extraction of regional cortical MK of at the center of the cortical layer: The cortical segmentation and parcellation was obtained from T1w image using FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). T1w of individual subjects were registered to the MNI template using FSL. The cortical segmentation maps were then transferred to the template space with the same transformation. Skeletonization function in FSL was used to extract the “cortical skeleton” based on the averaged cortical segmentation map in the template space. The cortical skeleton and cortical parcellation were inversely transferred to the native dMRI space. The MK measurement of a specific cortical gyrus was calculated by averaging the measurements on cortical skeleton voxels within this cortical label. The schematic pipeline is demonstrated in Fig.1. Details of these procedures can be found in the literature 6,10. Statistical analysis: To explore cortical microstructure maturation, linear regression was conducted between the cortical MK from a specific gyrus and age in both ASD and TD using R. Age and group interaction analysis of cortical MK was also conducted.Results

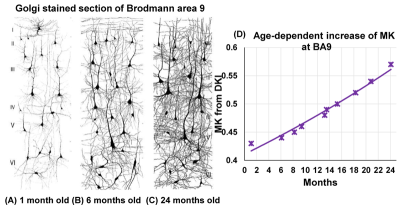

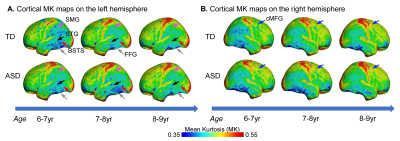

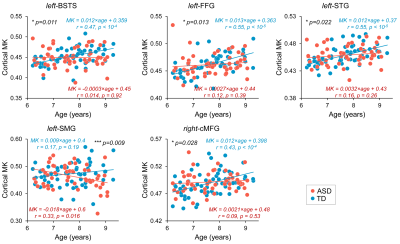

Although from a different age range, dramatic dendritic elaborations take place during development of infant cortex 11(Fig. 2A-C) and result in tremendously increased cortical microstructure complexity. Cortical MK from infant brain increases during the same time (Fig. 2D). Fig. 3A-B shows the cortical microstructural profiles with MK measurements of children with TD and ASD across three age groups (i.e., 6-7years, 7-8years, and 8-9years) on both hemispheres. Cortical MK values vary across the cortex, with high cortical MK predominantly found in the primary sensorimotor and occipital cortices and low MK found primarily in the temporal and parietal cortices. Significant age×group interactions were found in the cortical MK (Fig. 4) at five cortical areas indicated by arrows in Fig. 3, including the left banks superior temporal sulcus (BSTS, p=0.011; red arrows in Fig. 3), fusiform gyrus (FFG, p=0.013; gray arrows), superior temporal gyrus (STG, p=0.022; black arrows), supramarginal gyrus (SMG, p=0.009; pink arrows), and caudal middle frontal gyrus (cMFG, p=0.028; blue arrows). Such significant age×group interactions indicated a differential maturation of cortical microstructure in ASD. Compared with strong age-related increases of cortical MK in 6-9-year-old TD (blue dots, Fig. 4), relatively flattend or decreased maturational trends were observed in ASD (red dots).Discussion and conclusion

The present study offered unique noninvasive insight into the altered cortical cytoarchitectural maturation in children with ASD. Specifically, these altered cytoarchitectural maturation could be related to the altered changes in synaptogenesis and pruning in ASD3-5. The increased diffusion barriers reflected by increased cortical MK in 6-9-year-old TD might be associated with the increased cortical cellular density from the prolonged synaptogenesis1. The flatten cortical MK changes in ASD were primarily found in temporal regions, which may indicate altered auditory or social function in ASD. Using magnetoencephalography, differential maturation of auditory cortex activity has been found in the same cohort7. Fractional anisotropy (FA) from diffusion tensor imaging is widely used to characterize white matter microstructure. However, cortical FA during childhood development are at a noise level and cannot provide meaningful insight into cortical microstructural changes6. Cortical MK, on the other hand, could be an effective microstructural biomarker quantifying tissue microstructure complexity associated with non-Gaussian diffusion barriers6,12. Cortical MK measured on the “cortical skeleton” alleviated the partial volume effects in the relatively thin cortical mantle. The analysis of the relationship between cortical MK and cognitive and behavioral outcomes is under way.Acknowledgements

This study is funded by NIH R01MH092535, R01MH125333, R01EB031284, R01MH129981, R21MH123930, R01MH107506 and P50HD105354.References

1. Silbereis, J.C., Pochareddy, S., Zhu, Y., Li, M. and Sestan, N., 2016. The cellular and molecular landscapes of the developing human central nervous system. Neuron, 89(2), 248-268.

2. Penzes, P., Cahill, M.E., Jones, K.A., VanLeeuwen, J.E. and Woolfrey, K.M., 2011. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nature neuroscience, 14(3), 285-293.

3. Tang, G., Gudsnuk, K., Kuo, S.H., Cotrina, M.L., Rosoklija, G., Sosunov, A., Sonders, M.S., Kanter, E., Castagna, C., Yamamoto, A. and Yue, Z., 2014. Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron, 83(5), pp.1131-1143.

4. Avino, T.A., Barger, N., Vargas, M.V., Carlson, E.L., Amaral, D.G., Bauman, M.D. and Schumann, C.M., 2018. Neuron numbers increase in the human amygdala from birth to adulthood, but not in autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(14), 3710-3715.

5. Varghese, M., Keshav, N., Jacot-Descombes, S., Warda, T., Wicinski, B., Dickstein, D.L., Harony-Nicolas, H., De Rubeis, S., Drapeau, E., Buxbaum, J.D. and Hof, P.R., 2017. Autism spectrum disorder: neuropathology and animal models. Acta neuropathologica, 134(4), 537-566.

6. Ouyang, M., Jeon, T., Sotiras, A., Peng, Q., Mishra, V., Halovanic, C., Chen, M., Chalak, L., Rollins, N., Roberts, T.P. and Davatzikos, C., 2019. Differential cortical microstructural maturation in the preterm human brain with diffusion kurtosis and tensor imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(10), 4681-4688.

7. Green, H.L., Shen, G., Franzen, R.E., Mcnamee, M., Berman, J.I., Mowad, T.G., Ku, M., Bloy, L., Liu, S., Chen, Y.H. and Airey, M., 2022. Differential Maturation of Auditory Cortex Activity in Young Children with Autism and Typical Development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1-14.

8. American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing Inc

9. Glasser, M.F., Sotiropoulos, S.N., Wilson, J.A., Coalson, T.S., Fischl, B., Andersson, J.L., Xu, J., Jbabdi, S., Webster, M., Polimeni, J.R. and Van Essen, D.C., 2013. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage, 80, 105-124.

10. Yu, Q., Ouyang, A., Chalak, L., Jeon, T., Chia, J., Mishra, V., Sivarajan, M., Jackson, G., Rollins, N., Liu, S. and Huang, H., 2016. Structural development of human fetal and preterm brain cortical plate based on population-averaged templates. Cerebral Cortex, 26(11), 4381-4391.

11. Courchesne, E., Pierce, K., Schumann, C.M., Redcay, E., Buckwalter, J.A., Kennedy, D.P. and Morgan, J., 2007. Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron, 56(2), 399-413.

12. Zhu, T., Peng, Q., Ouyang, A. and Huang, H., 2021. Neuroanatomical underpinning of diffusion kurtosis measurements in the cerebral cortex of healthy macaque brains. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 85(4), 1895-1908.

Figures