5043

Elevated glutamine levels and activation of astrocytes involved in excessive excitatory neurotransmissions in autism spectrum disorder1Department of Functional Brain Imaging, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba, Japan, 2Department of Psychiatry, Nara Medical University, Kashihara, Japan, 3Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan, 4Department of Psychiatry, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 5Medical Institute of Developmental Disabilities Research, Showa University, Tokyo, Japan, 6Institute of Applied Brain Sciences, Waseda University, Tokorozawa, Japan, 7School of Human and Social Sciences, Tokyo International University, Kawagoe, Japan, 8Department of Neuropsychiatry, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan, 9Center for integrated human brain science, Brain Research Institute, Niigata University, Niigata, Japan, 10Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Showa University, Tokyo, Japan, 11Department of Language Sciences, Graduate School of Humanities, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Tokyo, Japan, 12Department of Molecular Imaging and Theranostics, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba, Japan, 13Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba, Japan, 14Kanagawa Psychiatric Center, Yokohama, Japan, 15Center for Brain Integration Research, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Psychiatric Disorders

We conducted MRS and PET to examine if enhanced excitatory tones occur and correlate with astroglial activations and/or diminished dopaminergic suppression of astrocytic functions in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) cases. MRS revealed elevated glutamate and glutamine levels associated with astroglial activation in ASD versus control anterior cingulate cortex, while there were also inverse correlations between glutamine levels and dopamine D1 receptor availability in this area of both ASD cases and controls. Hence, dopamine transmissions may repress astroglial glutamine synthesis independently of the ASD etiology, while astroglial activation in ASD could elicit augmented glutamate synthesis and consequent excitation of neuronal tones.INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction and restricted interest, and repetitive behaviors. An increased excitation-inhibition ratio of neuronal tones has been implicated in ASD at a non-clinical level,1, 2 while unequivocal clinical evidence for this alteration and its underlying mechanisms remains to be acquired. Enhanced glutamate (Glu) signals may arise from enhanced excitatory glutamatergic circuits, which can be affected by the activation of astrocytes and suppressive signaling downstream to dopamine neurotransmission.3 We aimed to examine our hypothetical view that astrocytic activation and dopaminergic dysfunctions were involved in the etiology of ASD.METHODS

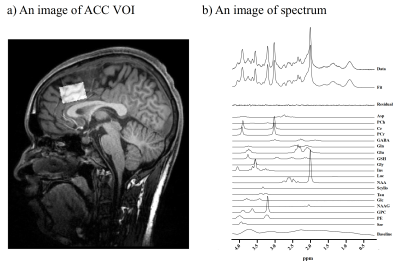

We enrolled 28 male subjects consisting of 18 ASD cases and 20 typically developed (TD) individuals. We assessed the autistic traits using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ). All MRI and MRS examinations were performed with a 3T scanner. They underwent MRS to evaluate levels of Glu, glutamine (Gln), gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA), and a marker of astroglial activity, myo-inositol (mI). We acquired MRS data with a semi-adiabatic spin-echo full-intensity acquired localized (SPECIAL) sequence4 (TR/ TE/ average = 3000 ms / 8.5 ms / 128). We also obtained a 3D volumetric acquisition of a T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence for anatomical images of the voxels of interest (VOIs). VOIs (30 × 20 × 20 mm3) were localized to the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), where disrupted structural5 and functional6 properties were reported in the ASD subjects (Figure 1). We analyzed MRS data using linear combination model (LCModel) software and corrected metabolite concentrations by segmenting gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the voxel VOI. Spectral SNR and linewidth were 76.6 ± 9.1, 0.028 ± 0.004 ppm. We examined PET scans with a specific dopamine D1 receptor radioligand, 11C-SCH23390, as reported previously.7 The binding of 11C-SCH23390 to DA D1Rs was quantified as non-displaced tissue (BPND). We applied independent sample t-tests and χ2-tests for the statistical examination of differences, and Pearson correlation or Spearman’s partial rank-order correlation analysis to test correlations. This study was approved by the institutional review boards and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.RESULTS

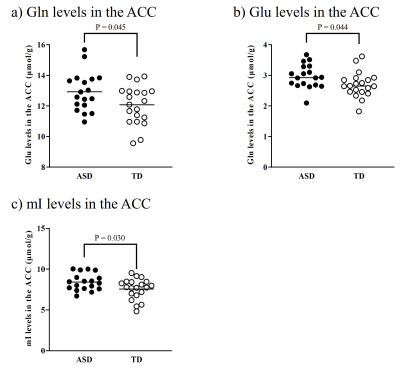

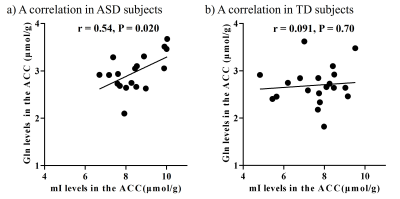

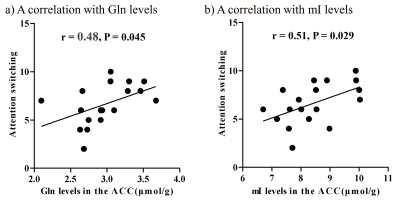

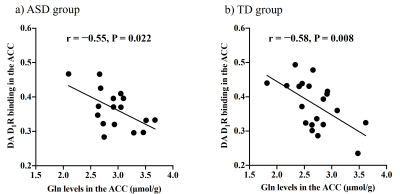

There were no significant differences in age and intelligence quotient in the two groups. We found significant increases of Glu (P = 0.045), Gln (P = 0.044), and mI (P = 0.030) levels in the ACC in individuals with ASD relative to those with TD (Figure 2). There were no significant differences in the ACC GABA levels between the ASD and TD groups (P = 0.44). We found significant positive correlations between mI and Gln levels in the ACC of individuals with ASD (r = 0.54, P = 0.020) but not TD subjects (r = 0.091, P = 0.70) (Figure 3). We also found significant positive correlations of AQ attention switching subscale score with Gln (r = 0.48, P = 0.045) and mI (r = 0.51, P = 0.029) levels in the ACC of individuals with ASD (Figure 4). As reported previously7, radioligand binding to DA D1Rs did not significantly differ between the ASD and TD groups (mean [SD], 0.36 [0.06] and 0.38 [0.07] in ASD and TD groups, respectively). We found significant negative correlations between DA D1R binding and Gln levels in the ACC of individuals with ASD (r = −0.55, P = 0.022) and TD (r = −0.58, P = 0.008) (Figure 5). By contrast, there were significant correlations of DA D1R binding with mI and Glu levels in the ACC of individuals with neither ASD nor TD (P > 0.05).DISCUSSION and CONCLUSION

In the current study, the SPECIAL sequence allowed us to evaluate Glu, Gln, and GABA levels separately and concurrently. This advanced MRS protocol clarified the elevated Glu and Gln levels, presumably reflecting enhanced excitatory neural tones in the ACC, in line with the evidence of the neural hyperexcitability of ASD.1, 2 We also found that ASD individuals presented increased levels of mI in the ACC, which is also in support of the hypothesized contribution of altered astroglial functions to the pathogenesis of ASD.8 Astrocytes play a critical role in Gln synthesis via an astrocyte-specific enzyme.9 Correspondently, the increased mI levels were correlated with Gln levels in the ACC of ASD individuals, implying that reactive astrocytes were associated with an increase in Gln synthesis in ASD. The autistic profile of attentional switching was associated with Gln and mI levels in the ACC, where neural activity was implicated in attentional controls.10 Additionally, both ASD and TD subjects exhibited a negative correlation of DA D1R bindings with Gln but not mI levels in the ACC, which may support the notion that the DA D1R signaling is involved in the Gln metabolism but is not specifically altered in ASD. As previous animal studies suggested suppressive roles of dopaminergic transmissions in the Gln synthesis3, 11, 12, we postulate that the modulation of Gln levels by D1R signaling is a physiological mechanism preserved in the ASD brains. Collectively, reactive astrogliosis might reinforce Gln synthesis and consequent excitatory tones in a manner independent of the inhibitory functions of dopaminergic transmissions in the ASD ACC.Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Clinical Research Section for their assistance as clinical coordinators, the staff of Department of Molecular Imaging and Theranostics for their support with MRI scans, the PET and MRI operators including Takasama Maeda for their imaging scans, the staff of the Department of Radiopharmaceutics Development for the radioligand synthesis, Atsuo Waki and his team for quality assurance of the radioligands, and Takashi Horiguchi for his assistance as research administrator, Jamie Near for his assistance of MRS protocol of SPECIAL sequence. We also wish to extend our gratitude to the research team of the Medical Institute of Developmental Disabilities Research at Showa University for their assistance in data acquisition.

The Joint Usage/Research Program of the Medical Institute of Developmental Disabilities Research, Showa University; SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation; the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists, 19K17101 to M.K.); MEXT KAKENHI grant numbers 19H01041; and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (the program for Brain/MINDS-beyond, 22dm0307105h0304, 22dk0207063h0001).

References

- Antoine MW, Langberg T, Schnepel P, et al., Increased Excitation-Inhibition Ratio Stabilizes Synapse and Circuit Excitability in Four Autism Mouse Models. Neuron, 2019. 101: 648-661 e4.

- Gkogkas CG, Khoutorsky A, Ran I, et al., Autism-related deficits via dysregulated eIF4E-dependent translational control. Nature, 2013. 493: 371-7.

- Rodrigues TB, Granado N, Ortiz O, et al., Metabolic interactions between glutamatergic and dopaminergic neurotransmitter systems are mediated through D1 dopamine receptors. J Neurosci Res, 2007. 85: 3284-93.

- Mekle R, Mlynarik V, Gambarota G, et al., MR spectroscopy of the human brain with enhanced signal intensity at ultrashort echo times on a clinical platform at 3T and 7T. Magn Reson Med, 2009. 61: 1279-85.

- Uppal N, Wicinski B, Buxbaum JD, et al., Neuropathology of the anterior midcingulate cortex in young children with autism. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2014. 73: 891-902.

- Dichter GS, Richey JA, Rittenberg AM, et al., Reward circuitry function in autism during face anticipation and outcomes. J Autism Dev Disord, 2012. 42: 147-60.

- Kubota M, Fujino J, Tei S, et al., Binding of Dopamine D1 Receptor and Noradrenaline Transporter in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A PET Study. Cereb Cortex, 2020. 30: 6458-6468.

- Gzielo K and Nikiforuk A, Astroglia in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22: 11544.

- Rose CF, Verkhratsky A, and Parpura V, Astrocyte glutamine synthetase: pivotal in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans, 2013. 41: 1518-24.

- Totah NK, Kim YB, Homayoun H, et al., Anterior cingulate neurons represent errors and preparatory attention within the same behavioral sequence. J Neurosci, 2009. 29: 6418-26.

- Chassain C, Bielicki G, Carcenac C, et al., Does MPTP intoxication in mice induce metabolite changes in the nucleus accumbens? A 1H nuclear MRS study. NMR Biomed, 2013. 26: 336-47.

- Darvish-Ghane S, Quintana C, Beaulieu JM, et al., D1 receptors in the anterior cingulate cortex modulate basal mechanical sensitivity threshold and glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Mol Brain, 2020. 13: 121.

Figures