5033

Improving Prostate Cancer Detection Using Bi-parametric MRI with Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks

Alexandros Patsanis1, Mohammed R. S. Sunoqrot1,2, Elise Sandsmark2, Sverre Langørgen2, Helena Bertilsson3,4, Kirsten Margrete Selnæs1,2, Hao Wang5, Tone Frost Bathen1,2, and Mattijs Elschot1,2

1Department of Circulation and Medical Imaging, Norwegian University of Science and Technology - NTNU, Trondheim, Norway, 2Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, 3Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology - NTNU, Trondheim, Norway, 4Department of Urology, St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, 5Department of Computer Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology - NTNU, Gjøvik, Norway

1Department of Circulation and Medical Imaging, Norwegian University of Science and Technology - NTNU, Trondheim, Norway, 2Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, 3Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology - NTNU, Trondheim, Norway, 4Department of Urology, St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, 5Department of Computer Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology - NTNU, Gjøvik, Norway

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Data Analysis, Deep Learning

This study investigated automated detection and localization of prostate cancer on biparametric MRI (bpMRI). Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) were used for image-to-image translation. We used an in-house collected dataset of 811 patients with T2- and diffusion-weighted MR images for training, validation, and testing of two different bpMRI models in comparison to three single modality models (T2-weighted, ADC, high b-value diffusion). The bpMRI models outperformed T2-weighted and high b-value models, but not ADC. GANs show promise for detecting and localizing prostate cancer on MRI, but further research is needed to improve stability, performance and generalizability of the bpMRI models.INTRODUCTION

Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) is a valuable tool for the detection and localization of prostate cancer (PCa)1. Computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems have been proposed to help overcoming certain limitations of conventional radiological reading of the mpMRI, such as its time-consuming nature and inter-observer variability2. In this work, we investigated the use of Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for the detection and localization of prostate cancer (PCa) using biparametric T2-weighted (T2W) and diffusion-weighted (DWI) MR images as input. We approach this task as a weakly supervised (i.e., only image-level labels used during training) image-to-image translation problem, an arena where GANs have previously proven to be successful3,4, also in the medical imaging domain5. This work builds on previous experience with GANs trained on T2W images alone6, and specifically aims to assess potential improvements when using biparametric MR images as input.METHODS

Dataset: We used in-house collected data of patients (N=811) suspected for PCa referred to prostate MRI at St. Olavs Hospital, Norway, from 2013 to 2019, approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in central Norway (ID 295013). Scan parameters are provided in Table 1. bpMRI images were used to train (N=421), validate (N=40), and test (N=350) several GAN models. Patients with biopsy-confirmed lesions (Gleason grade group (GGG) ≥ 1) were considered as cancer-positive patients. Patients with a negative biopsy or PIRADS < 3 without biopsy were considered cancer-negative. 3D co-registration of DWI to T2W was performed with Elastix v4.97 and applied to the DWI-derived high b-value and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images.Method: Implementation was according to our previously proposed end-to-end pipeline6, including Fixed Point GAN (FP-GAN)8 for image-to-image translation. Randomly cropped 2D images over the prostate area with a size of 128x128 pixels and a pixel spacing of 0.4x0.4 mm2 were used as input. Models were trained using three different scenarios: single, parallel, and merged modality training. In single modality training, each modality (T2W, high b-value, ADC) was trained individually. In case of parallel modality training, the model was trained on images from all modalities simultaneously. For merged modality training, the three image types were merged into a 3-channel image. Our goal was to translate images of unknown health status to cancer-negative images. FP-GAN8 has previously been shown to successfully translate between different and identical domains. Thus, if a negative patient is present, the model will not change anything, while for a positive patient the model will change the potential malignant area to translate the image to negative. The final output is a report image representing the difference between the input and generated image, which can be used for detection and localization of the malignant area. For each model, the patient-level area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) was calculated using the maximum intensity of the report images8, either as a performance metric to optimize the model (iterations, validation set) or to compare the performance of bpMRI vs single modality models (test set).

RESULTS

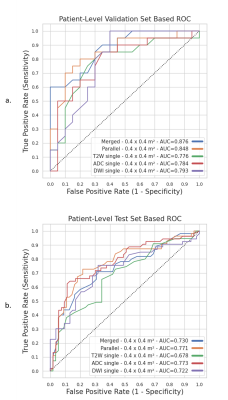

Patient-level validation AUC (Figure 2.a) for merged training was equal to 0.876 and for parallel training equal to 0.848, while this was 0.776, 0.784 and 0.793 for T2W, ADC and high b-value, respectively. Patient-level AUC for test set resulted in an AUC equal to 0.721 for merged training, 0.771 for parallel training, 0.678 for T2W, 0.773 for ADC and 0.722 for DWI (Figure 2.b).DISCUSSION

In this study, we trained two different FP-GAN8 models (merged and parallel training) on bpMRI data including T2W, ADC, and high b-value diffusion images. The results were evaluated in comparison to FP-GAN8 trained on the respective single modalities. Related GANs such as CycleGAN9 successfully perform image-to-image translation, but require labels from both the input and target domains during inference, which is not suitable when a patient with unknown health status is tested. StarGAN10 successfully addresses the need for labels during inference, but introduces irrelevant changes when translating between domains and fails for identical domain translation. FP-GAN successfully addresses this limitation by incorporating a conditional identity loss8. Our preliminary analysis suggests that both the merged (0.721) and parallel (0.771) bpMRI models increased patient-level AUC compared with T2W (0.678) alone, but not compared with ADC (0.773) alone. Interestingly, the drop in performance from validation to test set was substantially larger for both bpMRI models than for the ADC model. The higher AUC could be due to the substantially lower number of patients in the validation set compared with test set. Importantly, when only T2W was used, the model was unable to detect tumors in some patients (Figure 3). These results reflect clinical practice, where the ADC is regarded the most important imaging modality for tumor detection in the peripheral zone11, where most tumors appear. Thorough investigation of model performance per zone and GGG is subject to further research. Furthermore, we aim to improve the performance and generalizability of the model by using cohorts from different providers for training.CONCLUSION

Our preliminary results suggest that training conditional GANs on T2W and DWI improves the performance for detection of PCa in comparison to models trained on T2W alone, but not in comparison to models trained on ADC alone.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Turkbey B, Rosenkrantz AB, Haider MA, et al. Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2.1: 2019 Update of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2. Eur Urol. 2019;76(3):340-351. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.033

- Lemaître G, Martí R, Freixenet J, Vilanova JC, Walker PM, Meriaudeau F. Computer-Aided Detection and diagnosis for prostate cancer based on mono and multi-parametric MRI: a review. Comput Biol Med. 2015;60:8-31. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.02.009

- Zhang H, Xu T, Li H, et al. StackGAN++: Realistic Image Synthesis with Stacked Generative Adversarial Networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;41(8):1947-1962. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2856256

- Wang X, Yu K, Wu S, et al. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. In: Leal-Taixé L, Roth S, eds. Computer Vision – ECCV 2018 Workshops. Vol 11133. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer International Publishing; 2019:63-79. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11021-5_5

- Kazeminia S, Baur C, Kuijper A, et al. GANs for medical image analysis. Artif Intell Med. 2020;109:101938. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2020.101938

- Patsanis A, Sunoqrot MRS, Sandsmark E, et al. Prostate Cancer Detection on T2-weighted MR images with Generative Adversarial Networks. 2021 ISMRM & SMRT VIRTUAL CONFERENCE. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 15-20 May 2021.

- Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, Viergever MA, Pluim JPW. elastix: A Toolbox for Intensity-Based Medical Image Registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29(1):196-205. doi:10.1109/TMI.2009.2035616

- Rahman Siddiquee MM, Zhou Z, Tajbakhsh N, et al. Learning Fixed Points in Generative Adversarial Networks: From Image-to-Image Translation to Disease Detection and Localization. Vol 2019.; 2019:200. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00028

- Zhu JY, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation Using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). IEEE; 2017:2242-2251. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.244

- Choi Y, Choi M, Kim M, Ha JW, Kim S, Choo J. StarGAN: Unified Generative Adversarial Networks for Multi-Domain Image-to-Image Translation. ArXiv171109020 Cs. Published online September 21, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.09020

- Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, et al. PI-RADS prostate imaging–reporting and data system: 2015, version 2. Eur Urol. 2016;69(1):16-40.

Figures

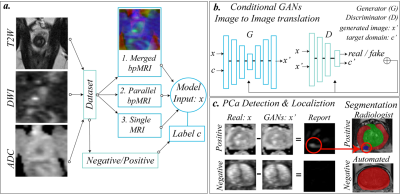

Figure 1: represents the

scenarios that were evaluated: merged, parallel and single modality training (a.).

GANs were trained using the patient's health status as image-level label. (b.) GANs

were trained to translate any patient status into a negative status. (c.) show

an example where the model changes the intensity of the malignant area of a

positive patient, located in the lower left part of the image, and an example

of a negative case, where the model makes no changes.

Figure 2: shows the AUCs for all

training scenarios, merged, parallel and single modality training. (a) In the

validation set, T2W had the lowest AUC (0.776) among all models, whereas the

highest AUC was obtained by using merged bpMRI (0.876). (b) In the test set, however,

the ADC (0.773) and parallel mpMRI model (0.771) showed the best performance.

Figure 3: shows the ability of the model to find the

malignant area on DWI and ADC images, while it could not find the malignant

area on T2W images for two different patients with cancer. The examples are

from parallel training of T2W, ADC and high b-value. The red circles show the

malignant area, while the green circles show the ability of the model to translate

the images and thus detect the lesions.

Table 1: contains information about the scan settings of

the in-house collected dataset. Calculated ADC and high b-value images (b=1500)

were derived from the DWI dataset for further processing.

Table 2: contains the

parameters of the GAN models. All trained models in this study used the same

model parameters. The GAN architecture is based on FP-GAN8.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/5033