5008

The link between superficial and deep white matter fibers1Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2Cardiff University Brain Research Imaging Centre (CUBRIC), Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 3Department of Radiology & Radiological Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 4Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Tractography & Fibre Modelling, White Matter, U-fibers, Diffusion MRI, Tractometry, Visualization

Here we visualized how superficial association fiber (SAF) systems relate to deep white matter bundles. We found that various shape features can be reliably extracted from those systems. The combination of superficial white matter tractography with traditional deep white matter bundles opens possibilities to study bundle-specific SAF in health and disease.Introduction

Superficial association fibers (SAF) represent more than half of the total white matter (WM) volume and yet, they remain largely understudied with diffusion MRI tractography due to technical limitations [1-3]. However, recent methodological advances in tractography have shown promising results in the extraction of SAF [4, 5] which sparked renewed interest in translating tractometric and volumetric analysis to SAF [6, 7]. SAF are traditionally analyzed at the local level via means of grey matter atlases to select individual U-shaped units [8] or clustering based on their shape and location [5, 9]. However, their relationship and associations with long-range WM has not been described. We seek to understand and visualize how SAF systems relate to deep WM bundles. We also investigate quantitative measurements linking SAF to deep WM bundles using shape descriptors [10] and assess their repeatability.Methods

DataDiffusion MRI data from 6 subjects acquired 5 times each using an ultra-strong gradient (300mT/m) 3T Connectom scanner were used (The Microstructural Image Compilation with Repeated Acquisitions (MICRA) dataset [11]). Preprocessing included slice-wise outlier detection, signal drift, Gibbs artifact, eddy current distortion and motion artifact, echo-planar image distortion, and gradient non-linearities. After preprocessing, diffusion data were upsampled to 1×1×1 mm3 to match the anatomical T1-weighted data [12] (TR/TE 2300/2.81 ms).

Tractography

SAF were extracted using a surface tracking method recently proposed by Shastin et al. [4]. Briefly, unconstrained probabilistic tractography (iFOD2 [13]) was performed seeding from a white-grey boundary mesh to generate 5M streamlines. Subsequent filtering identified streamlines up to 40 mm in length starting and ending in the cortex and coursing through the WM. Those selected (~1M) were truncated to remove intracortical portions at either end, forming the final SAF tractogram. In addition, TractSeg [14] was performed to obtain 38 major white matter bundles (after the exclusion of cerebellar, striatal, thalamic, and fornix tracts) using multi-shell multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution [15].

Analysis

The resulting bundle segmentations were then used as regions of interest (ROIs) to filter the SAF tractogram, resulting in 38 bundle-related SAF systems. We computed 10 shape descriptors [10] using SCILPY (github.com/scilus/scilpy) for each system and, to assess their repeatability, reported their coefficient of variations (CoV, averaged within subjects). Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between SAF and deep WM features were then computed across all data points (6 subjects × 5 sessions × 38 bundles). We also derive a new index, termed bundle-to-SAF ratio, by computing the volumetric ratio between deep and superficial fiber systems.

Results

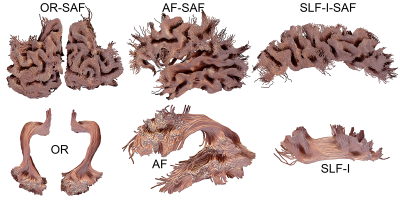

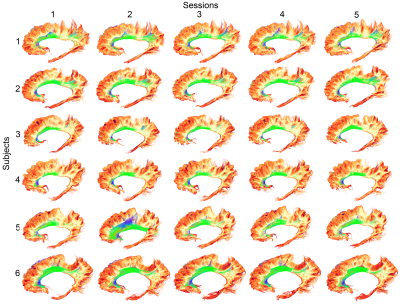

SAF visualizationSAF and bundles were successfully extracted in all participants. Figure 1 shows an overview of arbitrarily selected bundles (optic radiation, arcuate fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus) and associated SAF for a single example subject. Figure 2 shows a qualitative overview of the repeatability of the bundle-based SAF extraction for the cingulum bundle (green).

Shape features

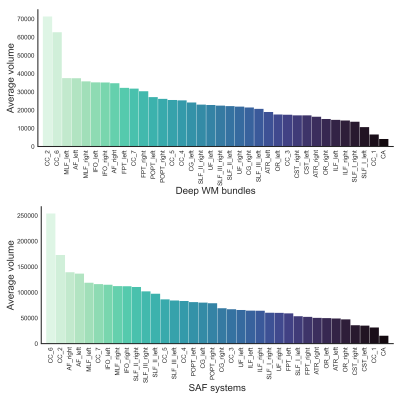

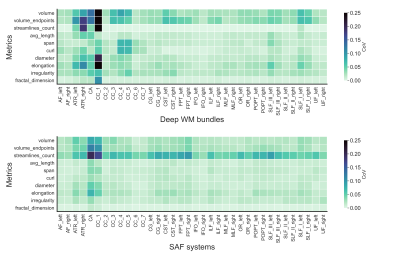

Figure 3 shows that the largest SAF systems (in terms of volume) are associated with the isthmus and genu sections of the corpus callosum (CC) whereas the smallest systems were found in the anterior commissure and rostrum of the CC. Significant Pearson correlation coefficients (p < 1e-10) were found between the following SAF and deep WM features: volume (r = 0.87), endpoints volume (r = 0.83), average length (r = -0.30), span (r = -0.21), curl (r = -0.35), diameter (r = 0.83), elongation (r = 0.62), irregularity (r = 0.77) and fractal dimension (r = 0.18).

Volume ratio

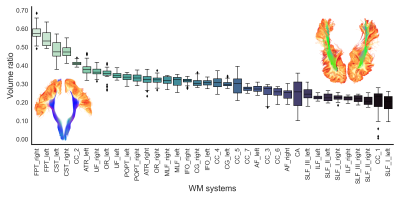

The ratio between both deep and superficial WM volume is shown in Figure 4. The largest ratios were observed in motor tracts, where SAF are only covering the superior extremity of the bundles. The smallest ratios were observed in the superior and inferior longitudinal fascicles where SAF are covering the entire body of the bundles - similar to what was described by Tusa & Ungerleider (1985) and Catani et al. (2003) [16, 17].

Repeatability

Finally, Figure 5 shows the repeatability of the extracted features, as expressed by the coefficient of variation (CoV), with most CoV < 5% across the board. The streamline count shows the most varying measures across SAF systems with low volume.

Discussion

From an anatomical point of view, visualizing how SAF relate to deep WM bundles should allow for a better understanding of brain connectivity overall [16, 17]. Combining [18] superficial SAF with traditional long-range tractography may open new avenues for connectomics & tractometry analyses, as well as improve the fidelity of whole-brain tractograms. The robust extraction of SAF systems may also shed light on the cortical hierarchical organization when combined with laminar functional MRI data. The validity of the extracted shape features remains to be investigated for SAF.Conclusion

Here, we have used a rich multi-shell microstructural MRI dataset acquired on an ultra-strong gradient 3T Connectom MRI scanner, combined with cutting-edge tractography approaches to visualize how SAF systems relate to deep white matter bundles. Using a repeatability analysis, we found that shape features can be reliably extracted from those systems. The combination of superficial white matter tractography with traditional deep white matter bundles opens possibilities to study bundle-specific SAF in health and disease [5-6, 19].Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Reveley, C, et al. PNAS (2015)

[2] Guevara, M, et al. Neuroimage (2020)

[3] Schilling, K, et al. Human brain mapping (2018)

[4] Shastin, D, et al. NeuroImage (2022)

[5] Xue, T, et al. IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2022)

[6] Schilling, K.G., et al. bioRxiv preprint (2022)

[7] Schilling, K.G., et al. bioRxiv preprint (2022)

[8] Guevara, M, et al. Neuroimage (2017)

[9] Zhang, F, et al. NeuroImage (2018)

[10] Yeh, F-C., Neuroimage (2020)

[11] Koller, K, et al. Neuroimage (2021)

[12] Dyrby, TB., et al. Neuroimage (2014)

[13] Tournier, J-D, et al. Neuroimage 202 (2019)

[14] Wasserthal, J, et al. Neuroimage (2018)

[15] Jeurissen, B, et al. Neuroimage (2014)

[16] Tusa, RJ., and LG. Ungerleider. Annals of neurology (1985)

[17] Catani, M, et al. Brain (2003)

[18] St-Onge, E, et al. Neuroimage (2018)

[19] Wang, S, et al. Human Brain Mapping (2022)

Figures