5002

Minimally invasive measurement of arterial and brain temperature in the mouse1Mouse Imaging Centre, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Physical Sciences, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Medical Imaging, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Thermometry, Metabolism, lanthanide, mice, brain

Brain temperature is an important physiological parameter that both reflects and modulates brain activity, but current in vivo thermometry methods are invasive and/or impractical for small animals. We present a minimally invasive method for measuring blood and brain temperature in mice using Tm-DOTMA and characterize the relationship between brain and blood temperature under isoflurane anesthesia. Brain temperature was strongly correlated and approximately equal to the temperature of the inflowing arterial blood, possibly reflecting the vasodilatory and metabolic suppressive effects of isoflurane. Application of this method with alternative anesthesia approaches would provide insight into brain temperature regulation in health and disease.Introduction

Brain temperature is an important physiological parameter that both reflects and modulates brain activity. It is tightly regulated under healthy conditions and changes in brain temperature in relation to core body temperature have been shown to be important in some pathological conditions 1-4. Current methods for measuring brain blood and tissue temperature in vivo are invasive and/or impractical for use in small animals 5, however development of less invasive methods would enable examination of brain temperature regulation in finely controlled disease models.We present a minimally invasive method for measuring blood and brain temperature in mice using the paramagnetic lanthanide complex Tm-DOTMA 6-7. Our method overcomes the SNR limitations imposed by the rapid clearance of Tm-DOTMA by prolonging its circulating half-life using probenecid and ensures that core body temperature is kept constant for the duration of the scan session.

Objective

To develop a minimally invasive MRI methodology to measure and characterize the relationship between brain, incoming arterial blood, and core body temperature in mice.Methods

Following isoflurane induction of anesthesia, tail vein catheterization and intraperitoneal injection of probenecid (200 mg/kg), male CD-1 mice (n = 12) were positioned on a custom-built bed for imaging. Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained within 0.1 °C of the initial temperature for the duration of the scan session by actively adjusting the bed temperature. Imaging was performed using a 7T Bruker scanner with a two-element cryoprobe. Pre-injection scans were acquired to confirm appropriate positioning of the mouse and to prescribe the slice locations for the brain and neck scans. Tm-DOTMA (5 µl of 0.2M solution/g) was then infused via the tail vein at 0.2 ml/min using a syringe pump. Multi-echo FLASH Tm and water neck and brain scans were acquired as follows: 1) Tm neck: TE/TR/α= [2.2, 2.35, 2.5 ms]/5.5 ms/90°, 0.4 mm in-plane resolution, 7 mm slice, offset frequency = -100 ppm, scan time ~ 15 min; 2) Tm brain: TE/TR/α= [2.162, 2.3, 2.5 ms]/5.83 ms/90°, 1.67 mm in-plane resolution, 6 mm slice, offset frequency -100 ppm, scan time ~ 41 min; 3) water neck: TE/TR/α= [3.5, 4, 4.5 ms]/50 ms/90°, 0.083 mm in-plane resolution, 7 mm slice, scan time ~ 2.4 min; 4) water brain: TE/TR/α= [4, 4.5, 5 ms]/50 ms/15°, 1.67 mm in-plane resolution, 6 mm slice, scan time ~ 9 min. The RF power was adjusted to compensate for the B1 inhomogeneity of the cryoprobe and ensure the desired flip angle was obtained at the region of interest.Thulium images were aligned with the corresponding water images using an estimated frequency shift based on the rectal temperature. The brain images were further shifted using a higher-resolution water image as a guide to centre the larger voxels on the brain. Voxels from the water neck image corresponding to the common carotid arteries and jugular veins were manually selected and paired with single overlapping voxels from the corresponding Tm neck image. A linear least squares fit was performed on the unwrapped phase data for both the water and Tm voxels in order to calculate the chemical shift difference between the Tm and water, which was then converted to temperature using calibration data. Outliers were identified and excluded from the analysis based on the root-mean-squared error and slope standard deviation of the Tm phase evolution fit.

Results

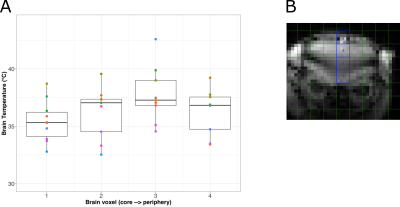

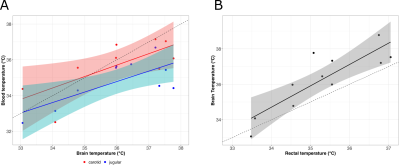

The average Tm images’ SNR was 10.8 (range 5.6-18.7) in the carotid arteries and 61.2 (range 7.3-234.11, depending on the voxel) in the brain. Representative images are shown in Figure 1.A temperature gradient of 0.7°C/mm was observed in the brain from the base of the brain (voxel 1) to the cortex (voxel 3) (Figure 2A) and the average brain temperature was found to be strongly correlated and approximately equal to the temperature of the inflowing blood in the carotid arteries (Figure 3A). This temperature was found to be greater than the rectal and jugular vein blood temperature by ~ 1.0 °C (Figure 3).

Discussion

Brain temperature is closely linked to brain function through several processes, most notably metabolism. In the awake healthy brain, heat produced from metabolism is balanced by heat removal via cerebral blood flow and heat exchange with the external environment 8. The data here, however, suggest that in this experiment, the brain is being warmed, rather than cooled, by the incoming blood. This seemingly unexpected trend could reflect the vasodilatory effect of isoflurane anesthesia, as well as its suppression of the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2), which together act to decouple the relationship between blood flow, metabolism, and temperature 9. The temperature gradient in the brain from the core to the cortex may reflect differences in arterial blood volume in these regions. The lower temperature of the most peripheral brain voxel is likely influenced by partial volume effects and the sagittal sinus.Conclusions

We have implemented a method to measure brain temperature in mice and have characterized the relationship between brain and blood temperature under isoflurane anesthesia. As the method is minimally invasive, it is well suited to imaging with alternative anesthesia approaches to study the relationship between temperature and metabolism in mouse models of neurological disease.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1.Wang H, Wang B, Normoyle KP, et al. Brain temperature and its fundamental properties: a review for clinical neuroscientists. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:307.

2. Greer DM, Funk SE, Reaven NL, et al. Impact of fever on outcome in patients with stroke and neurologic injury: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Stroke. 2008;39(11):3029-3035.

3. Karaszewski B, Wardlaw JM, Marshall I, et al. Measurement of brain temperature with magnetic resonance spectroscopy in acute ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(4):438-446.

4. Rossi S, Zanier E, Mauri I, et al. Brain temperature, body core temperature, and intracranial pressure in acute cerebral damage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(4):448-454.

5. Zhu M, Nehra D, Ackerman JJH, et al. On the role of anesthesia on the body/brain temperature differential in rats. J Therm Biol. 2004;29(7):599-603.

6. Heyn CC, Bishop J, Duffin K, et al. Magnetic resonance thermometry of flowing blood. NMR Biomed. 2017;30(11):e3772.

7. James JR, Gao Y, Miller MA, et al. Absolute temperature MR imaging with thulium 1,4,7,10- tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetramethyl-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (TmDOTMA-). Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(2):550-556.

8. Sukstanskii AL, Yablonskiy DA. Theoretical model of temperature regulation in the brain during changes in functional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(32):12144 LP - 12149.

9. Slupe A, Kirsch J. Effects of anesthesia on cerebral blood flow, metabolism, and neuroprotection. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38(12):2191-2208.

Figures