4997

Monitoring Temperature using Gradient Echo Imaging at 0.5T

Diego F Martinez1, Chad T. Harris2, Curtis N. Wiens2, Will B. Handler1, and Blaine A. Chronik1,3

1The xMR Labs, Physics and Astronomy, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 2Research and Development, Synaptive Medical, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Medical BioPhysics, Western University, London, ON, Canada

1The xMR Labs, Physics and Astronomy, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 2Research and Development, Synaptive Medical, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Medical BioPhysics, Western University, London, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Thermometry, Phantoms

Gradient Echo Proton Resonant Frequency (GRE-PRF) based thermometry, a standard approach to temperature mapping, was assessed at 0.5T. Experiments were performed using a 3 slice GRE acquisition at a resolution of 2x2x5mm and an update rate of 7.7s. Phantom and in-vivo measurements of the temperature stability yielded uncertainties of 0.78°C and 1.48°C respectively. Furthermore, a cooling experiment with the phantom showed excellent agreement to temperature changes simultaneously measured with a temperature probe. All results suggest that GRE-PRF thermometry is feasible at 0.5T.Introduction

Mid-field MR imaging is an active area of study [1-2] with renewed interest in implementing on these systems a variety of imaging methods usually reserved for higher fields. One such implementation is temperature mapping, which allows for non-invasive tracking of thermal therapies [3]. The standard approach to MR thermometry is the gradient echo proton resonance frequency (GRE-PRF) method. GRE-PRF thermometry in the mid-field is difficult as the longer T2* values cannot be optimally leveraged without comprising update rates or spatial resolution. In this work, we characterized GRE-PRF thermometry through a series of phantom and in-vivo stability and cooling experiments.Methods

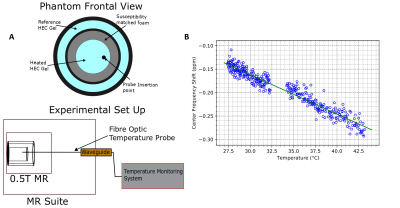

Phantom ProductionA custom double nested cylinder was produced, with the outer layer acting as a reference region, and the inner cylinder resting in polyurethane foam susceptibility matched using Pyrolytic Graphite in accordance with [4]. Schematic of the phantom is shown in Figure 1A. Hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC) was used as a tissue mimicking gel inside of the phantom, produced using the method described in Annex L of [5], for the solution with 96.85% water, 3% HEC [Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, Mo], and 0.15% NaCl, giving a relative dielectric permittivity of 78, conductivity of 0.47 S/m, density of 1001 kg/m. The HEC gel was then doped using Copper (II) Sulfate [Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, Mo] to a 2mM concentration to produce a T1 relaxation time similar to brain tissue (635 ms). The alpha parameter required for PRF thermometry was calculated by simultaneously measuring the center frequency and the temperature as a sample of heated HEC gel cooled.

Temperature Stability Measurement

Temperature stability imaging was performed on the phantom described above and on a healthy volunteer with informed consent in compliance with health and safety protocols. All imaging was performed using a 0.5T head-only MR scanner [Synaptive Medical, Toronto, Ontario] equipped with an 8 channel head-coil. In both cases, 64 repetitions of a 7.7s, 3-slice, GRE-PRF acquisition was run (TE = 23.75ms, TR = 86ms, BW= 20kHz, matrix size = 110x90, slice thickness = 5mm, slice gap = 5.5mm, FOV = 22x18cm, flip angle = 28°).

Temperature Tracking Experiment

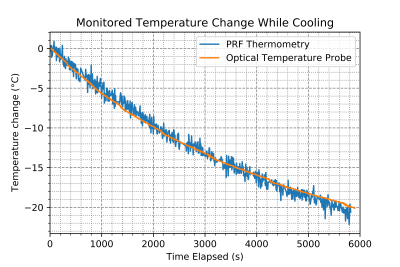

To validate the ability of tracking temperature change using the PRF method, the inner container in the phantom was heated in a hot water bath to ~60°C, then a fibre optic probe was inserted into the HEC gel acting as a thermometer, with tracking done on a NOMAD-Touch [Qualitrol; Fairport, NY] system (±1 °C; ±0.1 °C Resolution, -20 to 80 °C range, calibrated using a monitored hot water bath). The heated sample was placed in the phantom and a series of 702 repetitions of the GRE-PRF acquisitions described above were collected.

Temperature Map Reconstruction and Data Analysis

Phase differences were calculated relative to the first phase image acquired. A first order background phase correction was applied to the data based on the reference region in the phantom, and the outer rim of brain in the in-vivo case. This phase difference was converted to temperature, with the calibrated alpha parameter for the HEC gel and –0.01 ppm/°C for in-vivo measurements [3]. For the stability measurements, voxel-wise temperature uncertainty was calculated as the standard deviation of the temperature measurements over the time-course.

Results

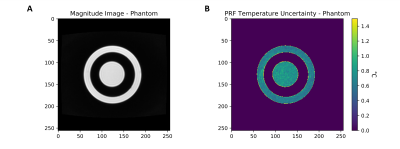

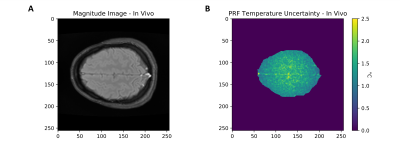

A schematic of the experimental set up, along with determination of the alpha parameter for HEC gel is shown in Figure 1, with α = (-8.74 ± 0.12) x 10-3 ppm/°C.The temperature uncertainty over 64 GRE-PRF acquisitions is shown in Figure 2, with average value of 0.78°C. In Figure 3, cooling of heated HEC gel is shown using GRE-PRF and the temperature probe. The PRF temperature shown is an average of a 4mmx4mm region near the probe. In-vivo temperature uncertainty for the GRE-PRF sequence is displayed in Figure 4. The average uncertainty over the slice shown is 1.48°C.

Discussion

Sub 1°C phantom temperature uncertainty over ~8 minutes of scan time shows the potential of temperature monitoring using this method, and as seen in Figure 3, the GRE-PRF method was indeed effective at tracking temperature. The TE used by this sequence is well below the optimal value of T2* at 0.5 T; however, average in-vivo temperature uncertainty was still below 2°C, providing sufficient precision. Future work will be done to fully characterize the change in temperature precision with echo time both for the phantom used in this study and in-vivo.A benefit to approaching temperature mapping using a relatively simple sequence such as GRE is the ease of implementation in a variety of scanners. With good matching to tracked temperature changes, and low uncertainty when imaging parameters are optimized, there is a strong case for its use as a standard method for PRF thermometry. A temporal resolution of 7.71s is adequate; however, further reduction using GRE with relatively long TE is difficult. For increased update rate, an EPI based PRF approach is likely a promising alternative.

Conclusion

This study has encompassed the development and validation of GRE-PRF temperature mapping on a 0.5T MR system. The method was able to accurately measure temperature in a cooling experiment, providing adequate temperature uncertainty in vivo with clinically acceptable update rates, spatial coverage, and image resolution.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Campbell-Washburn AE., et al. “Opportunities in interventional and diagnostic imaging by using high-performance low-field-strength MRI.” Radiology, 293(2):384– 393, 2019.

[2] Panther A., et al. (2019). A Dedicated Head-Only MRI Scanner for Point-of-Care Imaging. ISMRM Proceedings.

[3] Rieke V., Pauly KB. (2008). MR Thermometry. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 27(2): 376–390.

[4] Lee GC., et al. Pyrolytic Graphite Foam: A Passive Magnetic Susceptibility Matching Material. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2010;32:684–691.

[5] International Organization for Standardization. (2018). Assessment of the safety of magnetic resonance imaging for patients with an active implantable medical device (ISO/TS 10974:2018)

Figures

Figure 1: (A) Schematic of experiment, with phantom design on top and fibre optic probe routing on bottom. (B) displays measurement of the temperature response parameter alpha for Hydroxyethylcellulose gel, used in the phantom. Calculated slope of (-8.74 ± 0.12) x 10-3 ppm/°C

Figure 2: Temperature stability scans in an HEC gel phantom over 64 GRE-PRF acquisitions. (A) shows a structural image of the phantom, with regions filled with HEC visible and (B) shows the voxelwise temperature uncertainty in the phantom. Average temporal temperature uncertainty in the phantom was found to be 0.78°C.

Figure 3: Relative Temperature change measured using Gradient Echo PRF on a custom HEC gel temperature phantom. Comparison of temperature change in 4mm x 4mm region near a fibre optic probe show accurate temperature tracking.

Figure 4: An (A) Structural brain scan, and (B) temperature uncertainty of Single Echo Gradient Echo PRF thermal mapping over 64 GRE-PRF acquisitions. The average temperature uncertainty in the in vivo scan is 1.48°C.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4997