4991

Sparse regression-based delineation of air-motion artifacts for real-time correction of PRFS thermometry1Mechanical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands, 2Electrical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands, 3Radiotherapy, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Sparse & Low-Rank Models, Thermometry, susceptiblity aritfact correction

Proton resonance frequency shift-based MR thermometry is widely used to non-invasively monitor thermal therapies in vivo. However, further clinical integration in deep hyperthermia is hampered by intestinal air-motion induced susceptibility artifacts. We developed a sparse regression approach to delineate susceptibility artifact sources. The resulting mask is then used to correct the artifact using existing methods from quantative susceptibility mapping. We verified our approach by a heated phantom experiment equipped with a moveable air volume and temperature probes. Here, we found a reduction in the mean absolute error from 1.6 degrees Celsius to 0.4 degrees Celsius, near the air-motion artifact.Introduction

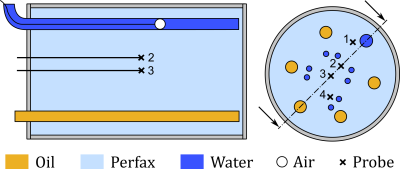

Proton resonance frequency shift (PRFS) MR thermometry is widely used to non-invasively monitor thermal therapies in vivo. However, (air-)motion artifacts frequently corrupt the measurements, hampering further integration of PRFS thermometry into clinical practice. Recently, computational methods from Quantitive Susceptibly Mapping were proposed to correct for air-motion artifacts1. However, these techniques, e.g., the PDF method2, can, in cases, also inadvertently remove the temperature induced phase shift, in addition to the motion artifact. Recent work aims to alleviate this problem by exploiting either model-based temperature estimators or total field inversion3, 4. Regardless, delineating susceptibility sources, i.e., mask selection, remains a crucial step in the artifact removal process. Mask selection based on anatomical scans is straightforward but is prone to errors as not all regions with a low MR signal correspond to air motion. We propose to compute a mask directly from the measured temperature using sparse regression. More specifically, we compute the mask by exploiting the knowledge that there are limited number of distinct susceptibility sources into a regularized optimization problem. In other words, we can exploit our prior knowledge regarding air-motion artifacts to separate temperature induced phase shifts from those caused by susceptibility artifacts. We verified our approach using a heated phantom that is equipped with a moveable air volume and temperature probes, see Figure 1 and for more details3.Method

We model the measured (B0-drift corrected) PRFS thermometry as $$T_{prfs}(r) = T(r) + D(r)*\Delta\chi(r).\tag{1}$$ Here, $$$T_{prfs},\ T,\ D,\ \Delta\chi$$$, and $$$*$$$ denote the measured temperature, the true temperature, a dipole kernel1,2, the magnetic susceptibility difference with respect to the baseline scan, and the convolution operator, respectively. Recall that we assume $$$\Delta\chi$$$ is sparse, i.e., there are only a few locations where the magnetic susceptibility changed with respect to the baseline scan.The PDF method estimates susceptibility sources by solving the following optimization problem2, $$\Delta\chi_{PDF}(r)=\arg\min_{\Delta\chi\in\Omega_{mask}}\int_{\Omega_{patient}}\big(T_{prfs}(r)-T_{est}(r)-D(r)*\Delta\chi(r)\big)^2dV.\tag{2}$$ Here, $$$T_{est}$$$ can be used to remove prior (model-based) temperature information from the PRFS measurement1,3. For simplicity, we choose $$$T_{est}=0$$$ for the remainder of this paper. Note that in (2), sparsity is enforced by constraining $$$\Delta\chi$$$ to the mask $$$\Omega_{mask}$$$. This naturally leads to the following tradeoff: If the mask is too large, we risk removing the temperature induced phase shift. If the mask is too small, we do not remove the motion artifact completely.

In this work, we compute the mask $$$\Omega_{mask}$$$ using sparse regression, $$\Delta\hat{\chi}(r)=\arg\min_{\Delta\chi}\int_{\Omega_{patient}}\big(T_{prfs}(r)-D(r)*\Delta\chi(r)\big)^2dV+\lambda\int_{\Omega_{patient}}|\Delta\chi(r)|dV.\tag{3}$$ From (3), we then compute $$$\Omega_{mask}$$$ as $$$\Omega_{mask}=\{r\in\mathbb{R}^3\mid|\Delta\hat{\chi}(r)|\geq threshold\}$$$. Note that, $$$\lambda$$$ controls the sparsity of the resulting mask estimate. We solve (3) efficiently using SR35. It may seem strange at first not to use the susceptibility estimate from (3) directly. However, it is known that sparse regression is excellent at finding the support of a function, but not necessarily well-suited to computing the best estimate5. For this reason, we threshold the minimizer (3) above the noise floor, and then, use the obtained mask in (2) to compute the final estimated susceptibly source. Finally, the corrected temperature is given by $$$T_{corrected}(r) = T_{prfs}(r)-D(r)*\Delta\chi_{PDF}(r)$$$.

The method is verified using a heated phantom equipped with a moveable air volume and temperature probes, see Figure 1 and for more details3.

Results

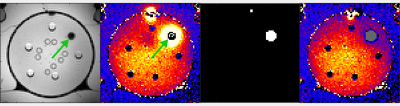

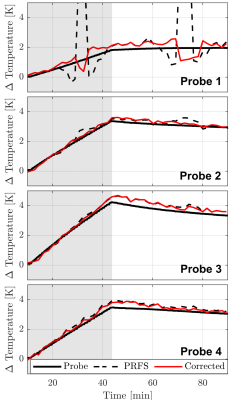

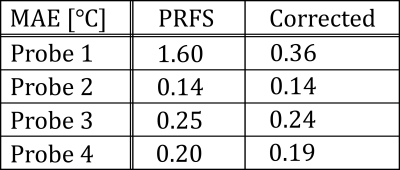

In Figure 2, we show the anatomical scan, PRFS measurement, identified mask, and artifact corrected temperature. Indeed, visually, sparse regression in combination with the PDF method appears to be successful at removing the air-motion artifact (indicated by the arrow). In Figure 3 and Table 1, we quantitively verify the artifact correction scheme using four temperature probes that serve as a ground truth. Here, the mean absolute error (MAE) at probe 1 decreased from 1.6 degrees Celsius to 0.4 degrees Celsius, indicating the susceptibility artifact is removed. Crucially, the MAE at the remaining (uncorrupted) probes remains similar, indicating that the temperature induced phase shift is not removed by our method.Conclusion

In this work, we showed that sparse regression techniques are effective at computing masks for air-motion correction. By computing the mask directly from the measured thermometry, this method avoids thresholding anatomical scans, which can be problematic. We demonstrated the efficacy of this method on a heated phantom experiment equipped with temperature probes and a moveable air volume. Here, we observed that the air motion artifact was successfully removed, while uncorrupted regions were not affected by our post-processing.Acknowledgements

This research is supported by KWF Kankerbestrijding and NWO Domain AES, as part of their joint strategic research programme: Technology for Oncology II. The collaboration project is co-funded by the PPP Allowance made available by Health$$$\sim$$$Holland, Top Sector Life Sciences & Health, to stimulate public-private partnerships.References

1. Wu, M., Mulder, H. T., Baron, P., Coello, E., Menzel, M. I., van Rhoon, G. C., & Haase, A. (2020). Correction of motion‐induced susceptibility artifacts and B0 drift during proton resonance frequency shift‐based MR thermometry in the pelvis with background field removal methods. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 84(5), 2495-2511.

2. Liu, T., Khalidov, I., de Rochefort, L., Spincemaille, P., Liu, J., Tsiouris, A. J., & Wang, Y. (2011). A novel background field removal method for MRI using projection onto dipole fields. NMR in Biomedicine, 24(9), 1129-1136.

3. Nouwens, S. A. N., Paulides, M. M., Fölker, J., VilasBoas-Ribeiro, I., de Jager, B., & Heemels, W. P. M. H. (2022). Integrated thermal and magnetic susceptibility modeling for air-motion artifact correction in proton resonance frequency shift thermometry. International Journal of Hyperthermia, 39(1), 967-976.

4. Boehm, C., Goeger‐Neff, M., Mulder, H. T., Zilles, B., Lindner, L. H., van Rhoon, G. C., ... & Wu, M. (2022). Susceptibility artifact correction in MR thermometry for monitoring of mild radiofrequency hyperthermia using total field inversion. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 88(1), 120-132.

5. Zheng, P., Askham, T., Brunton, S. L., Kutz, J. N., & Aravkin, A. Y. (2018). A unified framework for sparse relaxed regularized regression: SR3. IEEE Access, 7, 1404-1423.

Figures