4987

Dynamic 3D Stack-of-Radial Multi-Baseline PRF MR Thermometry using Compressed Sensing Reconstruction and Image-Based Navigation1Radiological Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Bioengineering, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 3Department of Engineering Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Thermometry, Motion Correction, Multi-baseline Thermometry

Multi-baseline proton resonance frequency-shift (PRF) MR thermometry can reduce motion-induced temperature errors in moving organs during MR-guided thermal therapy. However, previous methods had to compromise the spatial coverage to increase the temporal resolution for resolving motion. This work developed a dynamic 3D stack-of-radial MRI method using compressed sensing reconstruction and image-based navigation to enable motion-resolved multi-baseline PRF thermometry with 1.4-sec true temporal resolution. The proposed method achieved stable thermometry with volumetric coverage in free-breathing liver MRI without heating.

Introduction

Proton resonance frequency-shift (PRF) thermometry is widely used to monitor heating during MR-guided thermal therapies1. However, thermometry in moving organs remains challenging due to motion-induced phase changes causing temperature errors2. Multi-baseline MR thermometry has been proposed to address this problem by correcting the mismatch between the baseline and the image during treatment3-5. Due to limited acquisition speed, most studies only acquire a few or even one 2D slice to maintain sufficient temporal and spatial resolution6.Golden-angle-ordered 3D stack-of-radial MRI with k-space weighted image contrast (KWIC) reconstruction7-10 has been proposed for 3D MR thermometry with high spatiotemporal resolution. However, the true temporal resolution of KWIC reconstruction from view-sharing is still long and, therefore, susceptible to mixed contrast effects and motion blurring.

Compressed sensing (CS) reconstruction can be applied to thermometry to improve the true temporal resolution by reconstructing undersampled data. Previous studies have explored CS-based thermometry with additional phase constraints or temporal regularization11-15. However, these methods are sensitive to motion and have not been evaluated in moving organs.

In this study, we proposed a dynamic 3D stack-of-radial multi-baseline PRF MR thermometry framework using compressed sensing reconstruction and image-based navigation. The temperature mapping stability was evaluated in free-breathing liver MRI without heating.

Methods

Free-Breathing Liver MRI: In an IRB-approved and HIPAA-compliant study, free-breathing liver MRI was acquired in one healthy subject at 3T (Prisma, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) without heating. A golden-angle-ordered 3D stack-of-radial sequence16 was used, with TR=6.19ms, TE=[1.23, 2.46, 3.69, 4.92]ms, resolution=1.88x1.88x3mm3, FOV=360x360x48mm3, and flip angle=10°. 1500 radial angles were acquired with a total scan time (min:sec) of 2:56.Dynamic Image Reconstruction: After gradient calibration and correction16, the stream of radial data was divided into the baseline stage and the temperature mapping stage. The coil sensitivity maps were estimated using data acquired from the baseline stage. The radial data was split into sequential time frames, each containing consecutive radial angles for the desired temporal resolution (Fig. 1A and 1B).

The CS reconstruction was formulated as $$$m=argmin\left\{\left\| F\cdot S\cdot\widehat{m}-d \right\|^{2}_{2}+\lambda\left\|T\cdot\widehat{m}\right\|_{1}\right\}$$$, where m is the dynamic image to be reconstructed, d is multi-coil k-space data, F is the GPU-based NUFFT operator17, S is the estimated coil sensitivity map using a beamforming-based technique18, T is a total variation operation applied across three adjacent dynamic frames, and λ is the regularization parameter.

The reconstructed magnitude images were echo-combined using sum-of-squares. The reconstructed phase images were unwrapped along the echo direction and echo-combined7 to an effective TE=10ms.

Multi-Baseline PRF Thermometry using Image-Based Navigation: 48 frames were used to form the baseline library. A 2D image feature patch containing the liver dome was selected to characterize the motion in the superior/inferior (S/I) direction (Fig. 1C). The feature patch was used for baseline image selection using a structural similarity index measure (SSIM). The dynamic PRF temperature change (ΔT) maps were calculated on all slices. The same feature patch was also used to automatically track the S/I motion of tissue regions-of-interest (ROI) using a least-squares tracking algorithm19.

Analysis: Two 3x3-pixel ROIs were selected to measure temperature mapping stability over time (vs. constant body temperature) in terms of mean absolute error (MAE) and its standard deviation. The CS reconstruction results were compared with KWIC reconstruction using 13/144 radial angles for the innermost/outermost k-space regions.

Results

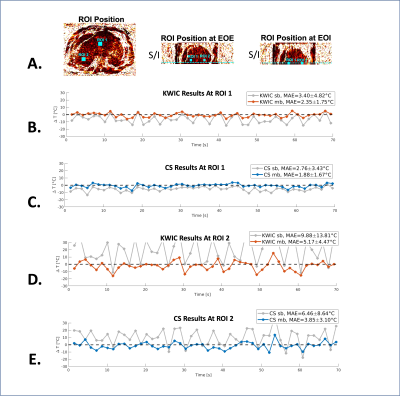

For CS reconstruction, we found a good balance between image quality and temporal fidelity with 13 radial angles per frame (1.4-sec temporal resolution) and λ = 0.02. Figures 2 and 3 compare the image quality and temporal fidelity using different reconstruction methods. Figure 3 also shows the 2D motion navigation results. Figure 4 shows the PRF temperature mapping results from KWIC and CS reconstruction using single-baseline and multi-baseline methods. Figure 5 shows the dynamic temperature measurements from two ROIs. MAEs were 1.88±1.67°C (ROI-1) and 3.85±3.10°C (ROI-2) using CS reconstruction and multi-baseline PRF.Discussion

Our proposed 3D stack-of-radial PRF thermometry method with CS reconstruction achieved volumetric coverage (16 slices) with an in-plane resolution of 1.88x1.88mm2 and a true temporal resolution of 1.4sec/frame. The proposed CS reconstruction resolved the motion effects in the liver (Fig. 2A) and improved spatial and temporal phase consistency (Fig. 2B and 3C).This is one of the first studies investigating motion-resolved CS-based PRF thermometry in moving organs. The proposed CS-based dynamic 3D thermometry framework successfully reduced motion-induced temperature errors across all slices (Fig. 4) and achieved better temperature stability (MAE<4°C) than KWIC (Fig. 5). The proposed image-based motion tracking technique could also be useful for monitoring thermal dose in moving organs during MR-guided thermal therapies.

There are several directions for improving the proposed method: 1) More subjects should be evaluated; 2) Improve spatial phase unwrapping. 3) The current reconstruction time was 7.1 seconds on average per slice per frame using GPU-NUFFT operation. The slice-by-slice reconstruction can be further accelerated by parallelization. 4) The proposed method should be validated in experiments with thermal therapy.

Conclusion

We developed a dynamic 3D stack-of-radial multi-baseline PRF MR thermometry framework using CS reconstruction and image-based navigation, which demonstrated the potential to achieve stable thermometry in moving organs.Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Siemens Medical Solutions USA and the Department of Radiological Sciences at UCLA.References

- Rieke, Viola, and Kim Butts Pauly. "MR thermometry." Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI 27.2 (2008): 376-390.

- Kägebein, Urte, et al. "Motion correction in proton resonance frequency–based thermometry in the liver." Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging 27.1 (2018): 53-61.

- Vigen, Karl K., et al. "Triggered, navigated, multi‐baseline method for proton resonance frequency temperature mapping with respiratory motion." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 50.5 (2003): 1003-1010.

- Grissom, William A., et al. "Hybrid referenceless and multibaseline subtraction MR thermometry for monitoring thermal therapies in moving organs." Medical physics 37.9 (2010): 5014-5026.

- de Senneville, Baudouin Denis, et al. "Motion correction in MR thermometry of abdominal organs: a comparison of the referenceless vs. the multibaseline approach." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 64.5 (2010): 1373-1381.

- Kuroda, Kagayaki. "MR techniques for guiding high‐intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatments." Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 47.2 (2018): 316-331.

- Svedin, Bryant T., et al. "Multiecho pseudo‐golden angle stack of stars thermometry with high spatial and temporal resolution using k‐space weighted image contrast." Magnetic resonance in medicine 79.3 (2018): 1407-1419.

- Jonathan, Sumeeth V., and William A. Grissom. "Volumetric MRI thermometry using a three‐dimensional stack‐of‐stars echo‐planar imaging pulse sequence." Magnetic resonance in medicine 79.4 (2018): 2003-2013.

- Zhang, Le, et al. "A variable flip angle golden‐angle‐ordered 3D stack‐of‐radial MRI technique for simultaneous proton resonant frequency shift and T1‐based thermometry." Magnetic resonance in medicine 82.6 (2019): 2062-2076.

- Dai, Qing, et al. "Dynamic 3D Stack-of-Radial PRF MR Thermometry to Monitor High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Heating: Validation in a Tissue Motion Phantom." Proceedings of the 31st annual meeting of ISMRM, London, UK. 2022.

- Zhao, Feng, et al. "Separate magnitude and phase regularization via compressed sensing." IEEE transactions on medical imaging 31.9 (2012): 1713-1723.

- Gaur, Pooja, and William A. Grissom. "Accelerated MRI thermometry by direct estimation of temperature from undersampled k‐space data." Magnetic resonance in medicine 73.5 (2015): 1914-1925.

- Cao, Zhipeng, John C. Gore, and William A. Grissom. "Low‐rank plus sparse compressed sensing for accelerated proton resonance frequency shift MR temperature imaging." Magnetic resonance in medicine 81.6 (2019): 3555-3566.

- Todd, Nick, et al. "Toward real‐time availability of 3D temperature maps created with temporally constrained reconstruction." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 71.4 (2014): 1394-1404.

- Shimron, Efrat, William Grissom, and Haim Azhari. "Temporal differences (TED) compressed sensing: a method for fast MRgHIFU temperature imaging." NMR in Biomedicine 33.9 (2020): e4352.

- Armstrong, Tess, et al. "Free‐breathing liver fat quantification using a multiecho 3 D stack‐of‐radial technique." Magnetic resonance in medicine 79.1 (2018): 370-382.

- Knoll, Florian, et al. "gpuNUFFT-an open source GPU library for 3D regridding with direct Matlab interface." Proceedings of the 22nd annual meeting of ISMRM, Milan, Italy. 2014.

- Mandava, Sagar, et al. "Radial streak artifact reduction using phased array beamforming." Magnetic resonance in medicine 81.6 (2019): 3915-3923.

- Wu, Holden H., et al. "Free‐breathing multiphase whole‐heart coronary MR angiography using image‐based navigators and three‐dimensional cones imaging." Magnetic resonance in medicine 69.4 (2013): 1083-1093.

Figures

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed dynamic 3D stack-of-radial MR thermometry method.

(A-B) During the baseline stage and temperature mapping stage, golden-angle-ordered 3D stack-of-radial data was acquired and split into dynamic frames for a sliding window CS reconstruction. The reconstructed images were used to generate motion-resolved temperature maps at each dynamic frame using multi-baseline PRF thermometry with image-based navigation. (C) Diagram of the multi-baseline PRF thermometry method using image-based navigation.

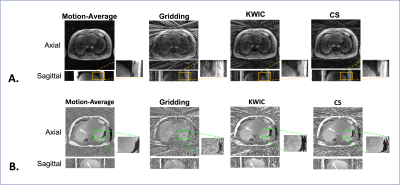

Figure 2: Image quality of the reconstructed images. (A-B) The magnitude/phase images were compared between reconstruction of all radial data (motion-averaged) and gridding, KWIC, and CS reconstruction of 13 radial angles (23x under-sampling). CS reconstruction reduced the streaking artifacts the most, even though KWIC utilized view-sharing from 144 spokes (2x under-sampling). KWIC and CS reconstruction results had sharper definition of the liver dome. CS reconstruction achieved better phase consistency. The white arrow indicates a region with residual esiphase wrapping.

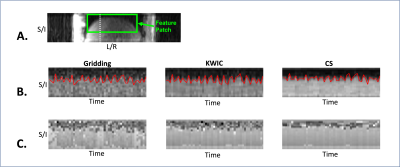

Figure 3: Image-based motion navigation using dynamic time frames.

(A) A 2D image feature patch (green box) was selected for image-based motion navigation. (B-C) A cross-section line (white dotted line in A) along the superior/inferior (S/I) direction was used to plot the temporal profiles from three reconstruction methods. Extracted respiratory motion signals (red) from the feature patch were superimposed on the temporal profiles. CS reconstruction has higher SNR, reduced streaking artifacts, and better magnitude and phase consistency over time.

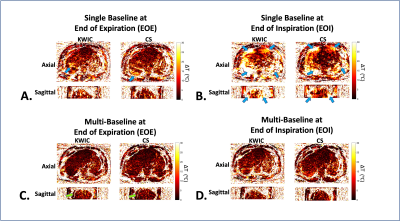

Figure 4: Dynamic free-breathing 3D stack-of-radial PRF MR temperature mapping results in the liver.

(A-B) Single-baseline PRF ΔT maps from time frames at EOE and EOI from KWIC and CS reconstruction. Blue arrows indicate motion-induced temperature errors. The single-baseline method showed more temperature errors at EOI. (C-D) Multi-baseline PRF ΔT maps at EOE and EOI. Green arrows in (C) indicate regions with residual spatial phase wrapping. Multi-baseline ΔT maps using CS reconstruction results exhibit reduced temperature errors at EOE and EOI.

Figure 5: Dynamic MR PRF temperature measurements.

(A) The S/I position of the selected ROIs was automatically tracked/translated across each time frame using image-based motion navigation. (B-E) The dynamic temperature measurements from ROI-1 and ROI-2 using KWIC (orange line) and CS (blue line). MAE and its standard deviation were calculated between the PRF measurements and constant body temperature (black dashed line). For both ROIs, multi-baseline (mb) PRF using CS reconstruction results achieved higher stability (low MAE and standard deviation).