4961

Evaluation of a model-based image reconstruction technique for accelerated point spread function encoded echo planar imaging1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Rochester, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Neuro, Clinical, radiologist, evaluation

A model-based image reconstruction (MBIR) platform was developed for accelerated point spread function encoded echo planar imaging. Beginning with retrospectively truncated data, images were reconstructed with the enhanced MBIR framework. These were compared by a team of neuroradiologists with images obtained using standard reconstructions from non-truncated datasets. Scores were assigned for evaluation criteria including high-contrast resolution (HCR), low-contrast detectability (LCD), signal to noise ratio (SNR), artifacts, and overall preference. Nonparametric statistical test results indicate preference for MBIR in HCR, LCD, and overall preference, with comparable results for SNR and artifacts. MBIR thus facilitates PSF-EPI acceleration, enhancing clinical practicality.Introduction

Echo planar imaging (EPI)1 is a commonly utilized fast imaging technique central to many advanced MRI applications. Despite very quick scan time, single-shot EPI is often relegated in practice to low-resolution imaging scenarios, with vulnerability to artifacts including geometric distortion due to low effective phase-encoding bandwidth and limited signal-to-noise ratio. Point spread function (PSF)-encoded EPI2–4 is a multi-shot EPI technique where auxiliary encoding enables reconstruction of undistorted images. While PSF-EPI enables distortion-free imaging with fewer artifacts than conventional EPI, the number of shots required to enable reconstruction of undistorted images (and thereby scan time) remains large without resorting to advanced, calibrated acquisition techniques5,6. As an alternative, this work developed an advanced model-based image reconstruction (MBIR)7 framework, extended beyond preliminary efforts8 to include regularization and a subspace representation of unknown magnetization to reduce scan times. Brain images obtained from retrospectively undersampled T2-weighted PSF-EPI data were reconstructed using our enhanced MBIR algorithm and compared to conventionally reconstructed brain images obtained from non-truncated datasets. Relative image quality and artifacts were assessed by neuroradiologists, comparing accelerated MBIR images to standard reconstruction images.Methods

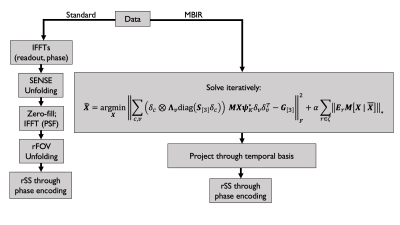

10 healthy volunteers were scanned on a Compact 3T MRI scanner9 following an IRB-approved protocol with T2-weighted PSF-EPI (T2-DIADEM)10. Imaging parameters were TR/TE=4600/80ms, 0.9/0.9/4 mm x/y/z resolution, 38 slices, 3x in-plane acceleration, 8x PSF encoding acceleration using reduced field of view (rFOV)3, 7/8 partial Fourier along PSF encoding for 28 shots (2:09 m:s scan time). In a baseline reconstruction from full-duration data for comparison, a PSF volume was accumulated with vendor-reconstructed in-plane images, which had been reconstructed with ASSET (GE’s SENSE-like11 reconstruction algorithm), before PSF volume unfolding and projection into distortion-free images4. For comparison, a second set of images was reconstructed by first subsampling from 28 to 18 shots (9/16 partial Fourier along PSF encoding; 1:23 m:s simulated scan time), and then running MBIR for 30 iterations in Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) using coil sensitivity profiles generated with ESPIRiT12.A comparison demonstrating signal processing workflow is shown in Figure 1. The standard reconstruction, serving as a comparison, comprises a modular sequence of steps necessary to accumulate a PSF volume from which an undistorted image can be obtained through root sum of squares summation through phase encodings. In contrast, MBIR directly estimates undistorted maps of basis expansion coefficients iteratively using the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM)13; a final image for display is obtained by projecting through the basis and then completing root sum of squares through phase encodings (additional details of this algorithm are provided in a separately submitted abstract).

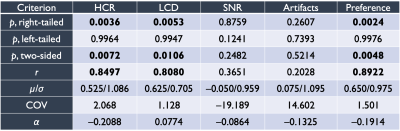

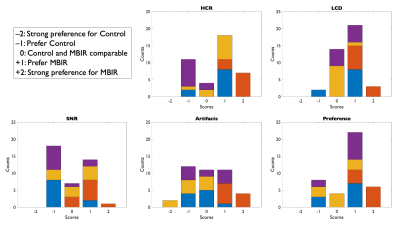

Image volumes from both reconstruction variants were randomly assigned blinded designations and scored independently by four board-certified neuroradiologists. Preferences were assigned as integer scores from –2 to +2 (negative preference for reconstruction ‘A’, positive preference for ‘B’) for all subjects. Evaluation criteria included high-contrast resolution (HCR), low-contrast detectability (LCD), signal to noise ratio (SNR), artifacts, and overall preference. After unblinding scores for evaluation, aggregated (summed) radiologists’ scores were assessed using nonparametric statistical tests in R as Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Using R, right-tailed, left-tailed, and two-sided tests were completed, also computing effect estimates as $$$r=Z/\sqrt{N}$$$. Inter-observer variability was quantified with Krippendorff’s $$$\alpha$$$14. Means, standard deviations, and coefficients of variation were also computed from score sets.

Results

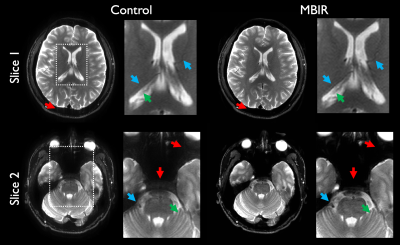

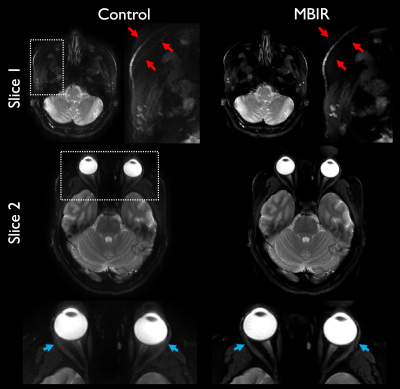

Example reconstructions are shown in Figure 2 comparing accelerated MBIR to full-duration standard reconstruction. In this example, differences in resolution and detectability are readily apparent, with comparable visual SNR, and considerable suppression of artifacts through MBIR. Figure 3 illustrates an additional comparison demonstrating artifact reduction through MBIR.Results of nonparametric statistical testing are tabulated in Figure 4. HCR, LCD, and overall preference favored accelerated MBIR with statistical significance, each with $$$r>0.8$$$ indicating considerable effect. SNR and artifacts did not significantly differ, exhibited low effect sizes, and showed substantial variability quantified by coefficients of variation.

Figure 5 contains histograms visualizing unblinded score counts, including distribution of score counts for individual readers, for all criteria. Score distributions are seen to skew positively for HCR, LCD, and preference; and center about zero for SNR and artifacts. Individual reader score counts indicate preferential differences in score assignments according to each reader’s interpretation.

Discussion and Conclusion

This work demonstrates the merits of using an advanced image reconstruction platform to achieve image quality, as assessed by radiologists, comparable to or better than full-duration standard reconstructions depending on assessment criteria. For data with a 1:23 simulated m:s scan time (a 35% reduction), images reconstructed with MBIR were assessed as having superior high-contrast resolution, low-contrast detectability, and overall preference. While SNR and artifacts were comparable, this is despite a reduction in available data from which to reconstruct images—and data truncation in this manner precisely reflects directly acquiring a shorter scan with fewer shots. Artifact suppression was not perfect for MBIR, reflecting sensitivity of PSF-EPI to through-shot signal effects, e.g. motion and flow.This work suggests MBIR for PSF-EPI is an enabling technology in reducing scan time and moves PSF-EPI closer to clinical practicality. A limitation at this time is long reconstruction times in a Matlab implementation of MBIR, which we expect to decrease considerably with a compiled implementation as would be done clinically.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH U01 EB024450, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.References

1. Mansfield P. Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes. J Phys C: Solid State Phys. 1977;10:L55.

2. Robson MD, Gore JC, Constable RT. Measurement of the point spread function in MRI using constant time imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38(5):733-740.

3. Zaitsev M, Hennig J, Speck O. Point spread function mapping with parallel imaging techniques and high acceleration factors: Fast, robust, and flexible method for echo-planar imaging distortion correction. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(5):1156-1166.

4. In MH, Posnansky O, Speck O. High-resolution distortion-free diffusion imaging using hybrid spin-warp and echo-planar PSF-encoding approach. Neuroimage 2017;148:20-30.

5. Dong Z, Wang F, Reese TG, et al. Tilted-CAIPI for highly accelerated distortion-free EPI with point spread function (PSF) encoding. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81(1);377-392.

6. In MH, Dong Z, Setsompop K, et al. An efficient reconstruction by combining tilted-CAIPI with eddy-current calibration for high-resolution distortion-free diffusion imaging using DIADEM. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 2019;0773.

7. Fessler J. Model-based image reconstruction for MRI. IEEE Signal Process Mag 2010;27(4):81-89.

8. Meyer NK, In MH, Kang D, et al. Model-based PSF-encoded multi-shot EPI reconstruction with low-rank constraints. Proc Intl Soc Magn Reson Med 2022;3484.

9. Foo TK, Laskaris E, Vermilyea M, et al. Lightweight, compact, and high-performance 3T MR system for imaging the brain and extremities. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80(5):2232-2245.

10. In MH, Campeau NG, Huston III J, et al. Rapid T2-DIADEM Echo-Planar Imaging as an Alternative to T2-FSE: A Clinical Feasibility Study. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 2021;0838.

11. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: Sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med 1999;42(5):952-962.

12. Uecker M, Lai P, Murphy MJ, et al. ESPIRiT - An eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: Where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(3):990-1001.

13. Boyd S, Parikh N, Chu E, et al. Distributed Optimization and Statistical Learning via the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers. Found Trends Mach Learn 2010,3(1):1-122.

14. Hughes J. KrippendorffsAlpha: Measuring Agreement Using Krippendorff's Alpha Coefficient. R package version 1.1-2.

Figures