4954

High-resolution single-shot spiral diffusion-weighted imaging at 7T using the expanded encoding model and compressed sensing1Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping (CFMM), Robarts Research Institute, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 2Department of Medical Biophysics, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Image Reconstruction

Reconstruction problems involving the expanded encoding model and field monitoring are typically solved using least squares optimization with the conjugate gradient method and early stopping as an implicit form of regularization. However, this is likely a suboptimal strategy for low SNR acquisitions, such as accelerated or high-resolution diffusion MRI. Hence, in this work we present an extension to the matMRI reconstruction toolbox that incorporates compressed sensing regularization. Results demonstrate that the expanded encoding model and compressed sensing regularization are complementary tools that mitigate artifacts from phase perturbations while permitting lower SNR conditions for high-resolution single-shot spiral diffusion-weighted imaging.Introduction

The expanded encoding model1–6 $$$A_{\textrm{exp}}$$$ incorporates spatially- and time-varying field perturbations for retrospective correction during image reconstruction. So far, these iterative reconstructions based on the conjugate gradient method have used early stopping as implicit regularization, but this optimization framework is likely suboptimal for low-SNR cases like diffusion MRI, making it more challenging to accelerate acquisitions or to increase the spatial resolution. The goal of this work was to combine $$$\ell_1$$$ regularization7-9 and the expanded encoding model for improved trade-offs between spatial resolution, readout time and SNR for single-shot spiral diffusion-weighted imaging at 7T. The compressed sensing reconstruction problem used can be described as follows:$$ \hat{x} = \textrm{argmin}_x \hspace{3mm} \| A_{\textrm{exp}}x-y \|_2^2 + \lambda \| \Psi x \|_1, \hspace{3mm} \textrm(1)$$

where $$$x$$$ is the image,$$$y$$$ is the acquired k-space data from the scanner,$$$\lambda \| \Psi x \|_1$$$ is the regularizer that promotes sparsity in the reconstruction, $$$\hat{x}$$$ , using a sparsifying transform $$$\Psi$$$, and $$$\lambda$$$ is the regularization weighting that balances the contribution of regularization in the optimization.

Additionally, an open-source GPU-enabled reconstruction toolbox, called 'MatMRI', that allows inclusion of the different components of the expanded encoding model, with or without CS, is introduced. The toolbox is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4495476.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained prior to scanning. Acquisitions were performed on a healthy volunteer on a 7-Tesla MRI scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM MRI Plus, Erlangen, Germany), with 80-mT/m gradient strength and a 400-T/m/s maximum slew rate. Concurrent field monitoring was performed using a 16-channel 19F commercial field-probe system integrated into a purpose-built radiofrequency coil (32-channel receive and 8-channel transmit).10 In vivo uniformly accelerated diffusion weighted single-shot spiral acquisitions were acquired with five acceleration factors (2x, …,6x) and three in-plane spatial resolutions (1.5, 1.3, and 1.1 mm). Remaining imaging parameters were as follows: slice thickness = 3 mm, number of slices = 10, TE/TR = 33/2500 ms, FOV = 192x192 mm2. A standard 6-direction DTI protocol, b = 1000 s/mm2, plus one b = 0 s/mm2 acquisition were acquired. A dual Cartesian gradient-echo acquisition was acquired for B0 estimation and computation of sensitivity coil profiles using ESPIRiT.11 The first echo image from this acquisition (ground truth), monitored field dynamics from the 1.5 mm resolution scans, field maps, and sensitivity coil profiles were used to generate forward expanded encoding models to simulate k-space data and to quantitatively compare reconstruction performance to the known ground truth after reconstruction when varying the number of components in the expanded encoding model. Moreover, acceleration factors, number of virtual coils, and noise levels were varied and their effect on reconstruction quality were assessed. Least-squares (LS) and compressed sensing (CS) reconstructions were performed for both the in vivo acquisitions and simulations to investigate the inclusion of CS-based regularization. For the selection of the regularization weighting, we adapted our previous method which involves automatically determining $$$\lambda$$$ from $$$WA_{\textrm{exp}}^\textrm{T}y$$$.9 Finally, from the in vivo reconstructions, we estimated their corresponding diffusion tensors and computed fractional anisotropy maps.12Results

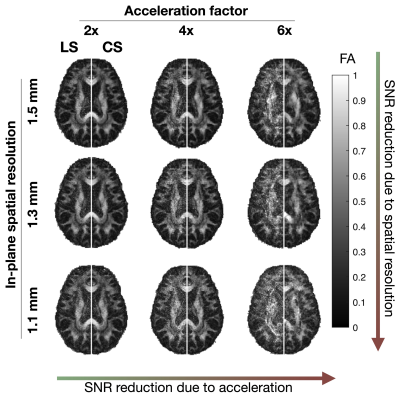

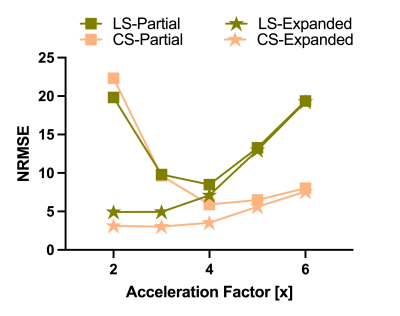

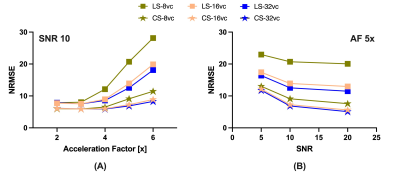

In vivo reconstructions (Figures 1-3) revealed that CS reconstruction effectively denoises the low SNR images and fractional anisotropy maps, enabling higher acceleration factors and higher spatial resolutions than LS reconstruction. Simulations (Figures 4-5) showed that the joint use of the expanded encoding model and CS reduces reconstruction error while varying components of the encoding model, acceleration factors, noise levels and number of virtual coils. While the expanded encoding model handles higher-order phase terms present at lower acceleration factors, CS-based regularization handles SNR reduction due to acceleration or noise.Discussion

In this work, we presented a regularized reconstruction framework that combines the expanded encoding model and CS. This promotes the use of higher acceleration factors, making higher spatial resolution acquisitions more feasible. As shown in the results, CS regularization is further motivated by the fact that when using higher acceleration rates and higher spatial resolutions, blurring due to both T2* decay and partial volume effects is diminished. Additionally, reduction of excessively long readout times reduces the likelihood of 19F field probe signals falling below threshold limits, which would impair the estimation of higher order coefficients for the expanded encoding model. Notably, when using the automatic selection of regularization weighting factor, CS did not introduce additional blurring in reconstructed in vivo images that can occur with wavelet-based over-regularization. While FA map integrity is not preserved at 6x acceleration, aliasing artifacts are reduced considerably using CS, suggesting that CS also improves missing data points for single-shot spirals. In our experiments, coil compression was used to reduce memory requirements and reconstruction time. Results suggest that for the levels of SNR commonly encountered in diffusion MRI, higher acceleration factors should be accompanied by a higher number of virtual coils (≥16) to preserve reconstruction quality, regardless of using LS or CS reconstruction. We recommend using 20-21 virtual coils for a 32-channel receiver as it provides a good trade-off between reconstruction time and image quality.Conclusion

The expanded encoding model and CS regularization are complementary tools for single-shot spiral diffusion MRI. Their combination enables higher in-plane spatial resolutions and higher acceleration factors and overcome limitations from the conventional least-squares reconstruction in lower SNR applications.Acknowledgements

Authors wish to acknowledge funding from the CIHR grant, the NSERC Discovery Grant, Canada Research Chairs, Ontario Research Fund, BrainsCAN-the Canada First Research Excellence Fund award to Western University, and the NSERC PGS D program. Finally, authors would like to thank Mr. Trevor Szekeres and Mr. Scott Charlton for assisting with data acquisition.References

1. Barmet C, Zanche ND, Pruessmann KP. Spatiotemporal magnetic field monitoring for MR. Magnet Reson Med. 2008;60(1):187-197. doi:10.1002/mrm.21603

2. Wilm BJ, Barmet C, Pavan M, Pruessmann KP. Higher order reconstruction for MRI in the presence of spatiotemporal field perturbations. Magnet Reson Med. 2011;65(6):1690-1701. doi:10.1002/mrm.22767

3. Wilm BJ, Nagy Z, Barmet C, et al. Diffusion MRI with concurrent magnetic field monitoring. Magnet Reson Med. 2015;74(4):925-933. doi:10.1002/mrm.25827

4. Wilm BJ, Barmet C, Gross S, et al. Single‐shot spiral imaging enabled by an expanded encoding model: Demonstration in diffusion MRI. Magnet Reson Med. 2017;77(1):83-91. doi:10.1002/mrm.26493

5. Engel M, Kasper L, Barmet C, et al. Single‐shot spiral imaging at 7 T. Magnet Reson Med. 2018;80(5):1836-1846. doi:10.1002/mrm.27176

6. Kasper L, Engel M, Barmet C, et al. Rapid anatomical brain imaging using spiral acquisition and an expanded signal model. Neuroimage. 2018;168:88-100. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.07.062

7. Candes EJ, Wakin MB. An Introduction To Compressive Sampling. Ieee Signal Proc Mag. 2008;25(2):21-30. doi:10.1109/msp.2007.914731

8. Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magnet Reson Med. 2007;58(6):1182-1195. doi:10.1002/mrm.21391

9. Varela‐Mattatall G, Baron CA, Menon RS. Automatic determination of the regularization weighting for wavelet‐based compressed sensing MRI reconstructions. Magnet Reson Med. 2021;86(3):1403-1419. doi:10.1002/mrm.28812

10. Gilbert KM, Dubovan PI, Gati JS, Menon RS, Baron CA. Integration of an RF coil and commercial field camera for ultrahigh‐field MRI. Magnet Reson Med. 2022;87(5):2551-2565. doi:10.1002/mrm.29130

11. Uecker M, Lai P, Murphy MJ, et al. ESPIRiT—an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: Where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magnet Reson Med. 2014;71(3):990-1001. doi:10.1002/mrm.24751

12. Tournier JD, Smith R, Raffelt D, et al. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage. 2019;202:116137. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116137

Figures