4945

Assessment of Oxidative Stress and Neuronal Activity Affected in PTSD Subjects1Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States, 2School of Health Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States, 3Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Indiana School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States, 4Department of Chemistry and Physics, Purdue Northwest University, Hammond, IN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Trauma, PTSD

We are reporting neurometabolic imbalances in post-traumatic stress disorder using edited and unedited single voxel spectroscopy with optimized HERMES data acquisition at 3T. We have investigated five brain regions that play a significant role in PTSD including insula, hippocampus, amygdala, anterior, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Our findings report the largest metabolic concentration changes in amygdala which moderates flight or fight state. Moreover, we observe decrease of primary neurotransmitter GABA in hippocampus, antioxidant GSH in DLPFC, and membrane turnover marker tCho across all brain regions.Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) involves persistent emotional reactivity to traumatic stimuli in environments where a threat is no longer present. Several robust neurobiological correlations of PTSD include decrease in size of hippocampus and amygdala, lower basal cortisol levels, and reduction in gray matter volume of prefrontal cortex3. These are mediated, in part, by biochemical imbalances of neural systems. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) is a non-invasive in-vivo imaging modality used to investigate the metabolic window on a wide range of diverse biochemical processes. This study evaluates edited and unedited single voxel spectroscopy (SVS) of ten clinically diagnosed PTSD participants and their age and gender-matched healthy controls to investigate metabolic dynamics of key neurometabolites and neurotransmitters. Certain brain regions are closely related to the underlying PTSD symptoms, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) which modulates decision making and working memory5. The insula controls autonomic functions through the regulation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, while the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) registers physical pain and emotional awareness10. The hippocampus (hippo) regulates memory consolidation, and the amygdala assesses threat-related stimuli5. Previous research has fragmentally demonstrated a significant role of MRS in understanding neuronal excitability in PTSD7. However, a more thorough study utilizing identical parameters over a wide range of metabolites and brain regions may further elucidate the dynamics of brain metabolites and neurotransmitters in PTSD.Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measurements

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Purdue University and informed consent was obtained. Ten PTSD participants (8 males, 2 females, age: 33.9±8.2) and ten healthy age and gender matched controls (8 males, 2 females, age: 33.5±8.5) underwent an hour-long brain scan using a 3T Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma MRI scanner. A vendor-supplied 64-channel receiver head coil was used across all participants.Sequences

Four brain regions (ACC, DLPFC, insula, hippo) have been investigated using edited and unedited MRS. 3D T1-weighted images (MPRAGE, TR/TE = 2300/2.98 ms, slice thickness = 1.2 mm, field-of-view = 256 × 256 mm2) were acquired to select a volume-of-interest (VOI). Unedited SVS was obtained using Point RESolved Spectroscopy (PRESS)1 using TE/TR:30/2000ms, 64 avgs, and VOI:40x25x27mm3. PRESS was chosen to better match the localization used in edited MRS. Edited MRS was acquired using Hadamard Encoding and Reconstruction of MEGA-Edited Spectroscopy (HERMES)2 with TE/TR:80/2000ms, 256 avgs, and VOI:40x25x27mm3. The fifth brain region, the amygdala, was only investigated using unedited MRS with semi-LASER (TE/TR:30/2000ms, 64 avgs, VOI: 15x15x15mm3) due to difficulty in acquiring reliable edited MRS from a small voxel.Data Analysis

For unedited MRS, Osprey6 was used for preprocessing consisting of the alignment of individual averages, averaging, polarity correction, residual water removal, linear baseline correction, and eddy current correction. Furthermore, voxel coregistration and segmentation was also completed in Osprey utilizing statistical parametric mapping (spm)9. Lastly, metabolite quantification was completed in LC Model11. N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), creatine (Cr), choline (Cho), myo-inositol (Ins), and glutamine+glutamamte (Glx) were reported using water referenced quantification and corrected for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Edited MRS data was analyzed in Gannet and CSF corrected values for inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), redox compound GSH, and Glx were reported. All statistical analysis (Shapiro-Wilk normality test, unpaired ttest, Grubbs outlier test) was performed using STATA SE12.Results

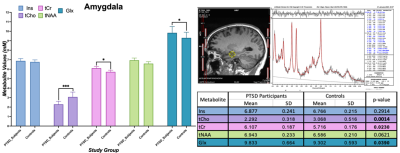

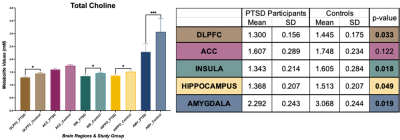

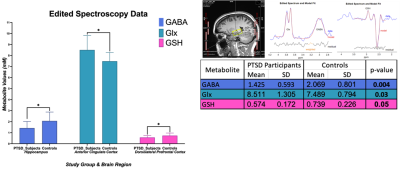

In amygdala, we found statistically significant changes in PTSD participants compared to healthy controls indicating neurotrauma with elevated glutamate-glutamine (Glx, p = 0.039), and creatine (tCr, p = 0.023) values. Additionally, a decrease in choline (tCho, p = 0.0014) seems to indicate neurotrauma related metabolic changes as shown in Figure 1. From single metabolite changes, tCho was decreased in four out of five brain regions (p = 0.02, 0.04, 0.02, 0.001). The fifth brain regions followed the same trend observed in Figure 2. Edited MRS depicted the significant role of three brain regions in PTSD as shown in Figure 3. Lower concentration of GABA (p =0.004) in the hippocampus, and glutathione (GSH, p =0.05) in DLPFC were observed in PTSD population. Increase of Glx in frontal brain regions has been previously reported in neurological disorders, which confirmed our findings in the ACC (p= 0.03).Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we are reporting the largest neurometabolic imbalances in the amygdala, the core component in neurobiological models of stress-related pathologies, which may reflect an exaggerated response of fear circuitry and explain PTSD symptoms, such as hypervigilance and hyperarousal4. Previous studies have indicated the importance of tNAA in PTSD, but here we are reporting an increase of tCho in four out of five brain regions. Edited spectroscopy has elucidated region specific biochemical profile of low concentration neurotransmitter GABA, which is a biological marker of vulnerability for development of mood disorders, anxiety, depression, and insomnia, symptoms commonly found in PTSD8. Furthermore, GSH, an antioxidant in charge of disposal of peroxides, is decreased in DLPFC of PTSD subjects due to the incomplete REDOX and active protection against toxicity5. Lastly, essential amino acids for brain metabolism and function (Glx) are increased in ACC. Further experiments will include a larger sample size and exploration of associations between neurometabolic changes and psychological surveys results from Central Nervous System Vital Signs13.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Purdue University Northwest, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Leslie A. Geddes Graduate Fellowship, and Bottorff Fellowship for their funding and support; Nathan Ooms, Dr. Xiaopeng Zhou, Dr. Gregory Tamer for their continuous work, expertise, and help with all the ongoing MRI projects at the Purdue MRI Facility.References

1.Bottomley, P A. (1987) doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632. 1987.tb32915.x

2.Chan, Kimberly L., et al. (2019) doi:10.1002/mrm.27702

3.Harnett, Nathaniel G., et al. (2017.) doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.04.010

4.Karl, Anke, et al. (2010.) doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.06.008

5.Michels, Lars, et al. (2014.) doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.09.007

6.Oeltzschner, Georg, et al. (2020) : 108827. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2020.108827

7.Price, Rebecca B., et al. (2009) doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.025

8.Schmitz, Taylor W., et al. (2017.) doi.org/10.17863/CAM.21776

9. Friston, K. J et al. (1995.) doi.org/10.1002/hbm.460020402

10. Wang, Dan et al. (2019) doi :10.3389/fnins.2019.00785

11. Provencher, S.W. (1993) doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910300604

12. StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

13. Gualtieri C.T. (2006) doi:10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.007

Figures