4935

Left DLPFC - left ACC resting state functional connectivity association with response to rTMS therapy of major depressive disorder1Cleveland Clinic Foundation, CLEVELAND, OH, United States, 2Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Psychiatric Disorders

High frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) targeted at left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (lDLPFC) is an increasingly popular therapy of patients with major depressive disorder, who are inadequately responsive to medication treatment. There is evidence of resting state functional connectivity (fcMRI) between lDLPFC and left anterior cingulate cortex (lACC) playing a role in rTMS efficacy. We performed a longitudinal study by scanning patients before and after 6-week long 10-Hz rTMS therapy. Patients with lower resting state low frequency blood oxygen level dependent fluctuation correlation and anticorrelation between lDLPFC and lACC responded better to rTMS therapy.Introduction

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non-invasive, non-convulsive neuromodulation method used to treat major depressive disorder (MDD) for patients who are inadequately responsive to medication treatment. High frequency rTMS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (lDLPFC) has been shown to be effective in inadequately responsive MDD.[1,2] Resting state functional connectivity (fcMRI) of several networks has been reported to be altered in MDD[3,4] and application of rTMS has been reported to modulate some of these fcMRI.[5,6] Baseline fcMRI measurements in patients with MDD have been performed before rTMS to compare networks in treatment nonresponders and responders[7] and to determine the most efficient area for rTMS application in the lDLPFC. rTMS therapy has been reported to normalize subgenual hyper connectivity in the medial prefrontal–medial parietal default mode network (DMN) without any effect on frontoparietal central executive network and to induce anticorrelated connectivity between the DLPFC and the medial prefrontal DMN.[8] Increased dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC)–subgenual cingulate and subgenual cingulate–DLPFC fcMRI has also been associated with improvement in MDD after rTMS.[9] lDLPFC–left ACC (lACC) fcMRI has been reported to be higher in patients with MDD than in healthy controls [10] and DLPFC-subgenual ACC anticorrelation (in fcMRI) has been reported to be associated with better rTMS outcome.[11,12]However most of these studies either (i) used DMPFC rTMS,[7,9] or (ii) were not longitudinal in nature.[12] [8] We have performed a longitudinal study with lDLPFC as the target to address the most clinically standard rTMS protocol[13,14] to investigate both maximum correlation and anticorrelation of lDLPFC-lACC fcMRI before and after rTMS, with their possible role in predicting response to rTMS.Methods

Ten patients (57±12 y, 3 male) with MDD were scanned at a Siemens 3T Prisma scanner (Erlangen, Germany) using a 20-channel coil head/neck coil under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol. Each patient was scanned within a week before starting rTMS therapy (pre-treatment scan) and within 1 week after the end of 6 weeks of therapy (post-treatment scan). The inclusion criteria required satisfying DSM-V-TR[15] criteria for inadequate response to at least 1 antidepressant treatment during current major depression episode (17-item HAM-D score>15) despite treatment with an adequate dosage for at least 6 weeks. [16]Whole-brain resting-state functional connectivity scans were performed with patient’s eyes closed: 80° FA; 29-ms TE; 2800-ms TR; 31 axial slices; 4mm slice thickness; no gap; 128×128 matrix; 256×256 mm2 FOV; 1954-Hz/pixel bandwidth; 137 repetitions; 6-min 26-s scan time. Physiologic fluctuations were monitored by pulse plethysmograph and respiratory bellow, and bite bars were used to minimize motion. 30 sessions of 6-week long rTMS was administered by a MagPro R-30 magnetic stimulator (Magventure, Farum, Denmark; 10-Hz frequency, 120% of motor threshold (minimum energy to trigger thumb movement) power, 4-s stimulus duration, 26-s inter-train interval, 75 pulses/train, 3000 total number of pulses).

fcMRI data preprocessing consisted of (i) rejection of 1st 4 data-points from timeseries, (ii) applying a brain mask using the Brain Extraction Tool,[17] (iii) correction for physiologically induced fluctuations and slice acquisition timing using Physiologic EStimation by Temporal Independent Component Analysis,[18] (iv) volume- and slice-wise motion correction using SLice-Oriented Motion COrrection and [19] (v) registration of fcMRI data to anatomical MPRAGE scan collected during the same session using Boundary-Based Registration.[20]

lDLPFC and lACC region of interest (ROI) generation: Although the functional extent of the ACC matches well with its anatomical delineation, this is not the case for the DLPFC, which spans sections of the superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri as well as Brodmann areas 9 and 46. To maintain generalizability, we used a functional atlas characterizing the DLPFC across multiple cognitive states.[21] This atlas is in MNI152 space, so we applied an inverse warp to the image described above to map the DLPFC in each patient’s native fMRI space. Because of the functional/anatomical congruency of the ACC, this region was mapped to the patient’s space using Destrieux atlas.[22]

fcMRI quantitative analysis consisted of (i) quadratically detrending preprocessed data, (ii) temporal filtering with a [0.01 0.08] Hz pass band, (iii) conducting a seed-based search to find the maximal correlation and anticorrelation between the lDLPFC and lACC ROIs using a spherical kernel with a 2-mm radius, and (iiv) conversion of correlations to z-scores using a nonparametric transform based on whole-brain correlations to the seed.[23]

Results

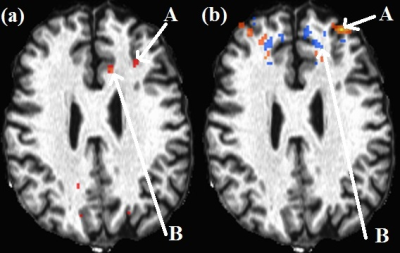

One subject data were discarded due to motion. Representative lDLPFC-lACC correlation and anticorrelation maps are shown in Fig. 1. Paired T-tests showed no significant difference in correlation/anticorrelation before and after rTMS (N=9). HAM-D scores significantly decreased from 20±3 to 10±7 (P<0.001). Plots of pre-rTMS fcMRI correlation/anticorrelation versus changes in HAM-D scores and post-rTMS HAM-D scores are shown in Fig. 2. Changes (decrease) in HAM-D scores correlated significantly with decrease in pre-rTMS correlation and anticorrelation, while post-rTMS HAM-D scores significantly correlated with pre-rTMS correlations.Conclusion

Results from this study suggest that patients with both lower lDLPFC-lACC correlation and anti-correlation respond better to rTMS therapy.Acknowledgements

Cleveland Clinic Research Program Committee partially funded this project.References

[1] Lefaucheur JP, Andre-Obadia N, Antal A, Ayache SS, Baeken C, Benninger DH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin Neurophysiol 2014;125:2150-206.

[2] George MS, Post RM. Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for acute treatment of medication-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:356-64.

[3] Helm K, Viol K, Weiger TM, Tass PA, Grefkes C, Del Monte D, et al. Neuronal connectivity in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018;14:2715-37.

[4] Mulders PC, van Eijndhoven PF, Schene AH, Beckmann CF, Tendolkar I. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depressive disorder: A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;56:330-44.

[5] Fan J, Tso IF, Maixner DF, Abagis T, Hernandez-Garcia L, Taylor SF. Segregation of salience network predicts treatment response of depression to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroimage Clin 2019;22:101719.

[6] Philip NS, Barredo J, Aiken E, Carpenter LL. Neuroimaging Mechanisms of Therapeutic Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Major Depressive Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2018;3:211-22.

[7] Downar J, Geraci J, Salomons TV, Dunlop K, Wheeler S, McAndrews MP, et al. Anhedonia and reward-circuit connectivity distinguish nonresponders from responders to dorsomedial prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2014;76:176-85.

[8] Liston C, Chen AC, Zebley BD, Drysdale AT, Gordon R, Leuchter B, et al. Default mode network mechanisms of transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression. Biol Psychiatry 2014;76:517-26.

[9] Salomons TV, Dunlop K, Kennedy SH, Flint A, Geraci J, Giacobbe P, et al. Resting-state cortico-thalamic-striatal connectivity predicts response to dorsomedial prefrontal rTMS in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014;39:488-98.

[10] Davey CG, Harrison BJ, Yucel M, Allen NB. Regionally specific alterations in functional connectivity of the anterior cingulate cortex in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med 2012;42:2071-81.

[11] Cash RFH, Zalesky A, Thomson RH, Tian Y, Cocchi L, Fitzgerald PB. Subgenual Functional Connectivity Predicts Antidepressant Treatment Response to Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: Independent Validation and Evaluation of Personalization. Biol Psychiatry 2019;86:e5-e7.

[12] Fox MD, Buckner RL, White MP, Greicius MD, Pascual-Leone A. Efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation targets for depression is related to intrinsic functional connectivity with the subgenual cingulate. Biol Psychiatry 2012;72:595-603.

[13] McClintock SM, Reti IM, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, Dubin M, Taylor SF, et al. Consensus Recommendations for the Clinical Application of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) in the Treatment of Depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2018;79.

[14] Philip NS, Carpenter SL, Ridout SJ, Sanchez G, Albright SE, Tyrka AR, et al. 5Hz Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to left prefrontal cortex for major depression. J Affect Disord 2015;186:13-7.

[15] Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th Text Revision ed.). Atlington, VA: American Psychatric Association; 2013.

[16] Tierney JG. Treatment-resistant depression: managed care considerations. J Manag Care Pharm 2007;13:S2-7.

[17] Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 2002;17:143-55.

[18] Beall EB, Lowe MJ. Isolating physiologic noise sources with independently determined spatial measures. Neuroimage 2007;37:1286-300.

[19] Beall EB, Lowe MJ. SimPACE: generating simulated motion corrupted BOLD data with synthetic-navigated acquisition for the development and evaluation of SLOMOCO: a new, highly effective slicewise motion correction. Neuroimage 2014;101:21-34.

[20] Greve DN, Fischl B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage 2009;48:63-72.

[21] Shirer WR, Ryali S, Rykhlevskaia E, Menon V, Greicius MD. Decoding subject-driven cognitive states with whole-brain connectivity patterns. Cereb Cortex 2012;22:158-65.

[22] Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A, Halgren E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 2010;53:1-15.

[23] Lowe MJ, Mock BJ, Sorenson JA. Functional connectivity in single and multislice echoplanar imaging using resting-state fluctuations. Neuroimage 1998;7:119-32.