4931

Abnormal dynamic function connectivity pattern in first-episode, drug-naïve adult patients with major depressive disorder1Radiology, First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2College of Biomedical Engineering and Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 3Psychiatry, First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 4GE Healthcare, Shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, fMRI (resting state)

Objective: To explore the specific FC change patterns of MDD by combining sFC and dFC.

Methods: 37 MDD and 36 matched HCs were included in this study. The differences of sFC and dFC between two groups were compared.

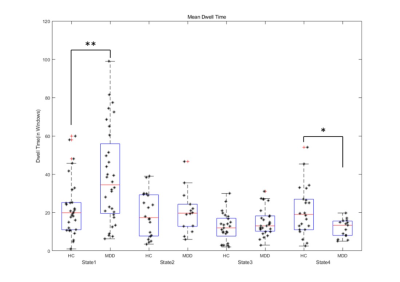

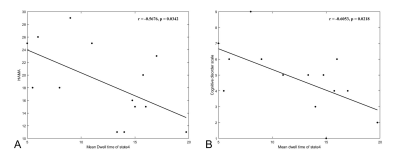

Results: Compared to HCs, patients showed less time in the anti-correlated state between higher-order and lower-order networks and longer dwell time in the whole-brain weakly connected state. The mean dwell time of state 4 was negative correlation with the behavioral scale score in patients.

Conclusions: These disrupted dFC patterns provide new clues to understanding the neuropathology of state-dependence in MDD.

Objective

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is known to be characterized by disrupted brain functional connectivity (FC) patterns, while the dynamic change mode of different functional networks is unclear[1, 2]. This study aimed to characterize specific alterations pattern on intrinsic FC in MDD by combining static FC (sFC) and dynamic FC (dFC).Methods

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data were acquired from 37 first-episode, drug-naïve adult patients with MDD and 36 matched healthy controls (HCs). The sFC and dFC were analyzed using complete time-series and sliding window approach, respectively. Both sFC and dFC differences between groups were analyzed and correlation between disease severity and aberrant FC were explored.Results

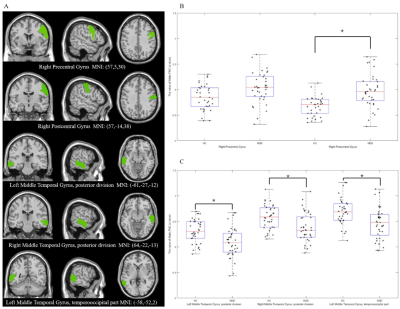

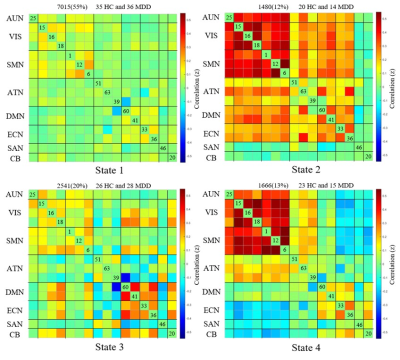

The sFC results showed lower negative sFC between the right angular gyrus and the right postcentral gyrus as well as weaker sFC strength within the bilateral middle temporal gyrus in MDD patients compared to HCs (FIG1). The global dFC analysis clustered the intrinsic brain FC into four states among subnetworks (FIG2). Compared with HCs, patients with MDD demonstrated shorter fraction time and mean dwell time in anti-correlation state between higher-order and lower-order networks (State 4), and increased mean dwell time in the weakly-connected state (State 1) between and within subnetworks (FIG3). The mean dwell time of state 4 was negative correlation with the HAMA score and the cognitive impairment scores of HAMD (FIG4) in patients.Discussion

Static FC patternsPatients with MDD exhibited near-zero connectivity between the right angular gyrus (part of the ECN) and the right postcentral gyrus (a core part of the SMN), relative to the stronger anti-correlation strength in healthy controls. The weaker relative negative correlation between ECN and SMN is in accordance with the hypothesis that MDD patients are more strongly involved in their inner world than healthy individuals [3]. This hypothesis is partially supported by previous research showing the association between weakened ECN connectivity strength and increased rumination in MDD [4]. Such a significant separation between large-scale networks may entail disrupted allocation of cognitive resources leading to an inability to disengage from ruminative cognition [5].

Dynamic FC patterns

Further dynamic FC analysis showed four different network states in populations with MDD and healthy controls. We observed that patients with MDD had less mean dwell time and fraction time in the state4 which characterized by anti-correlation between high-order and low-order networks, and in particular, a strong positive correlation between and within the lower-order networks. Lower-order perceptual networks (i.e., SMN, VIS, and AUD) are associated with sensory perception and motor processes and play a central role in information transfer with the external environment [6]. It has been proposed that anticorrelated networks may imply that networks continuously compete with each other for control of shared brain resources [7, 8]. The high integration within and between lower-order networks in the antagonistic state may reflect normal top-down regulatory mechanisms. At this point, motion and perception are regulated by higher-order cognitive networks, which are closely related to the process of cognitive-to-action transition [2, 9]. The shorter dwell time in this antagonistic state that we found in MDD patients may imply that they were unable to convert effective cognitive processing into action. Hebbian learning theory states that “cells that fire together, wire together”. Based on this, it has been proposed that continuous access to the functional network makes it more stable in the resting state and may strengthen underlying structural connections. [10]. This hypothesis is supported by cognitive training research, which has shown that working memory training not only changes FC, but also induces variations in the structural connectome [11]. As such, we hypothesized that individuals who are less likely to enter the anti-correlated state in their lives may be at higher risk of developing depression.

The negative correlation between mean dwell time of State4 and the severity of cognitive disorder was an interesting finding. The cognitive deficits may reduce the likelihood of making appropriate choices in the decision-making process. For example, executive dysfunction in the context of depression may lead to de-inhibition and poor decision making in specific contexts, which is considered a risk factor for suicide attempts [12]. The shortened State 4 mean dwell time may reveal that the weakened anti-correlation between brain area cannot maintain a high degree of functional specificity. Thus, abnormal disengagement from the antagonistic state may underlie difficulties in negative information processing, thereby negatively biasing cognitive processing.

Another important result was that MDD patients spent more time in a globally hypo-connected state. The results shed light on previous static FC findings of reduced global connectivity and lack of integration between subnetworks in the resting-state FC in MDD [13, 14]. Whole-brain weak connected states are associated with self-referential thought processing [15]. The predominance of weak connected states not only indicates a disruption in the normal integration of whole-brain networks in MDD, but may also be due to greater investment in self-focused rumination in resting states [2, 16].

Conclusions

Our findings suggested that the absence of antagonistic state and the dominance of weakly-connected state between higher-order and lower-order networks may be the characteristic FC alteration in MDD. These disrupted dFC patterns provide new clues to understanding the neuropathology of state-dependence in MDD.Acknowledgements

We thank all the subjects included in this study.References

1. Hamilton JP, Chen MC, Gotlib IH (2013) Neural systems approaches to understanding major depressive disorder: an intrinsic functional organization perspective. Neurobiol Dis 52(4-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2012.01.015.

2. Yao Z, Shi J, Zhang Z, Zheng W, Hu T, Li Y, Yu Y, Zhang Z, Fu Y, Zou Y, Zhang W, Wu X, Hu B (2019) Altered dynamic functional connectivity in weakly-connected state in major depressive disorder. Clin Neurophysiol 130(11):2096-2104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2019.08.009.

3. Peng D, Liddle EB, Iwabuchi SJ, Zhang C, Wu Z, Liu J, Jiang K, Xu L, Liddle PF, Palaniyappan L, Fang Y (2015) Dissociated large-scale functional connectivity networks of the precuneus in medication-naïve first-episode depression. Psychiatry Res 232(3):250-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.03.003.

4. Connolly CG, Wu J, Ho TC, Hoeft F, Wolkowitz O, Eisendrath S, Frank G, Hendren R, Max JE, Paulus MP, Tapert SF, Banerjee D, Simmons AN, Yang TT (2013) Resting-state functional connectivity of subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in depressed adolescents. Biol Psychiatry 74(12):898-907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.036.

5. Hamilton JP, Furman DJ, Chang C, Thomason ME, Dennis E, Gotlib IH (2011) Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol Psychiatry 70(4):327-333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003.

6. Northoff G, Hirjak D, Wolf RC, Magioncalda P, Martino M (2021) All roads lead to the motor cortex: psychomotor mechanisms and their biochemical modulation in psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry 26(1):92-102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0814-5.

7. Sonuga-Barke EJ, Castellanos FX (2007) Spontaneous attentional fluctuations in impaired states and pathological conditions: a neurobiological hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 31(7):977-986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.02.005.

8. Anticevic A, Cole MW, Murray JD, Corlett PR, Wang XJ, Krystal JH (2012) The role of default network deactivation in cognition and disease. Trends Cogn Sci 16(12):584-592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.10.008.

9. Christopher L, Duff-Canning S, Koshimori Y, Segura B, Boileau I, Chen R, Lang AE, Houle S, Rusjan P, Strafella AP (2015) Salience network and parahippocampal dopamine dysfunction in memory-impaired Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 77(2):269-280. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24323.

10. Figueroa CA, Cabral J, Mocking RJT, Rapuano KM, van Hartevelt TJ, Deco G, Expert P, Schene AH, Kringelbach ML, Ruhé HG (2019) Altered ability to access a clinically relevant control network in patients remitted from major depressive disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 40(9):2771-2786. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24559.

11. Caeyenberghs K, Metzler-Baddeley C, Foley S, Jones DK (2016) Dynamics of the Human Structural Connectome Underlying Working Memory Training. J Neurosci 36(14):4056-4066. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1973-15.2016.

12. Cao J, Ai M, Chen X, Chen J, Wang W, Kuang L (2020) Altered resting-state functional network connectivity is associated with suicide attempt in young depressed patients. Psychiatry Res 285(112713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112713.

13. Zhang L, Wu H, Xu J, Shang J (2018) Abnormal Global Functional Connectivity Patterns in Medication-Free Major Depressive Disorder. Front Neurosci 12(692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00692.

14. Luo L, Wu H, Xu J, Chen F, Wu F, Wang C, Wang J (2021) Abnormal large-scale resting-state functional networks in drug-free major depressive disorder. Brain Imaging Behav 15(1):96-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-019-00236-y.

15. Marusak HA, Calhoun VD, Brown S, Crespo LM, Sala-Hamrick K, Gotlib IH, Thomason ME (2017) Dynamic functional connectivity of neurocognitive networks in children. Hum Brain Mapp 38(1):97-108. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23346.

16. Berman MG, Misic B, Buschkuehl M, Kross E, Deldin PJ, Peltier S, Churchill NW, Jaeggi SM, Vakorin V, McIntosh AR, Jonides J (2014) Does resting-state connectivity reflect depressive rumination? A tale of two analyses. Neuroimage 103(267-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.027.

Figures