4915

An unsupervised deep learning-based method for in vivo high resolution Kidney MRI motion correction1Centre for Advanced Imaging, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Australia, 2Australian Research Council Training Centre for Innovation in Biomedical Imaging Technology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 3School of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Motion Correction

A primary challenge for in vivo kidney MRI is the presence of different types of involuntary physiological motion, affecting the diagnostic utility of acquired images due to severe motion artifacts. Existing prospective and retrospective motion correction methods remain ineffective when dealing with complex large amplitude nonrigid motion artifacts. We introduce an unsupervised deep learning-based method for in vivo kidney MRI motion correction. We demonstrate that our deep learning model achieved the average structural similarity index measure (SSIM) of 0.76±0.06 between the reconstructed motion-corrected and ground truth motion-free images, showing an improvement of about 0.33 compared to the corresponding motion-corrupted images.

Introduction

Nephrons are microscopic structures of the kidney which play an essential role in renal filtration of blood. Nephron number varies significantly between individuals reflecting developmental and acquired factors, and the trajectory of nephron number reflects the risk of developing renal disease1,2. Current gold standard methods of nephron quantification have limited clinical utility due to the need for excised kidney or biopsy samples. High resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide a non-invasive tool for whole-kidney nephron visualisation and quantification in vivo3,4. However, a major obstacle to its use for this purpose is different types of involuntary physiological motion, due to respiration, vascular pulsation and gastrointestinal movements. This results in severe artifacts which affect the diagnostic utility of the acquired images and the accuracy of parameter estimation based on the images1,2. The human glomerulus has an average diameter of ~150 µm and voxel intensity blurring caused by small tissue displacements preclude accurate imaging at this resolution2.State-of-the-art prospective navigator-based motion correction technique5-8 require increased acquisition time, need additional equipment and their use is often limited by scanner hardware9 or the type of MRI pulse sequence. The clinical utility of existing retrospective methods has been hampered by the need for costly collection of additional accurate motion pattern information9-11, or due to computationally costly and lengthy post-acquisition iterative optimisation processes12,13. Correction of local deformations due to nonrigid motion artifacts remains a major unresolved challenge for current prospective9 and retrospective techniques11.

Deep learning14 (DL)-based post-reconstruction motion correction methods have three potential advantages over traditional approaches: i) the capacity to extract and learn complex nonlinear patterns efficiently15-17, ii) highly efficient estimation of a new image, enabling their near real-time application15, and iii) can be trained on images acquired from different MRI pulse sequences, facilitating their clinical utility.

Previous DL-based MRI motion detection and motion correction methods18-22 have mainly focused on brain MRI. These studies have considered rigid-body motion artifacts only and have assumed less severe motion artifacts compared to those usually observed in abdominal imaging. Here, we propose a DL-based method to correct complex motion artifacts in high resolution kidney MRI scans.

Methods

We formulated this problem as direct single-step DL-based image-to-image translation between motion-corrupted and motion-free image domains. We conducted ex vivo 3T MRI scans of 13 porcine kidneys (due to the anatomical homology between pig and human kidney) using a 3D T2-weighted turbo spin echo sequence with TR/TE=2000/52ms, turbo-factor=15, echo-spacing=17.2ms, receiver-bandwidth=128 Hz/pixel, signal average=4, resolution=156×370×156 µm and matrix size=456×96×768. To create the motion-corrupted image set, we simulated respiratory motion artifacts as a phase error along the phase encoding direction in the k-space of the motion-free ex vivo MR images23 using:$$\phi(k_y) =\frac{k_y*D*\sin({\lambda}k_y + φ)}{N_y},$$

where D denotes the organ displacement (2-3cm), ky (-π<ky<π) is the phase encoding step in the k-space, Ny represents the total number of phase encoding steps, and λ (0.2-0.7 Hz) and φ (0-π/4) are the frequency and the phase of a sinusoidal wave corresponding to respiratory movement, respectively. The images from both domains were segmented to coronal slabs of 128×128×3 (i.e., 3-channel inputs) for training.

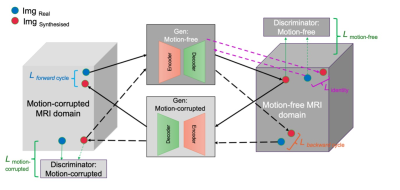

To deal with the case of not having exact voxel-wise pairs from corresponding motion-free and motion-corrupted images, we used a cycle consistency generative adversarial network, an unsupervised deep neural network structure24, as the basis of our motion correction model and added normalised cross correlation cycle consistency (NCC-CycleGAN) to enforce the alignment between the reconstructed motion-corrected and motion-free images. Cycle-GAN can be applied to unpaired images from two image domains, with the network being trained to learn the non-linear mapping between them. The Cycle-GAN consists of two generator-discriminator pairs associated with each image domain (Figure 1).

We added the normalised cross correlation between real image x∈X and the corresponding double-transformed synthesised image G(F(x))∈X to the forward and backward cycle consistency losses proposed in the original Cycle-GAN work24.

Results and Discussion

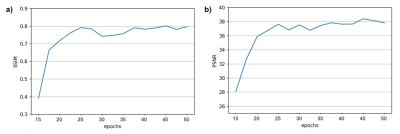

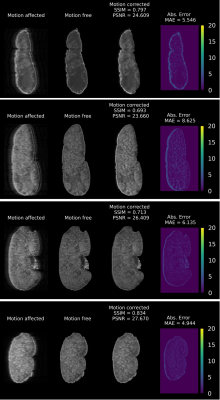

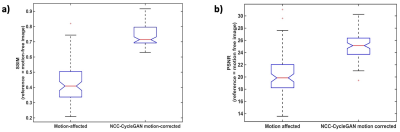

Figure 2 shows the training evaluation on a test set, consisting of 20% of the image samples, using structural similarity index (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR). After 50 epochs, the average SSIM and PSNR on the test set reached 0.8 and 38, respectively.Figure 3 shows four examples of motion correction using the NCC-CycleGAN model to correct respiratory motion artifacts imposed on four coronal slabs of a kidney sample from our held-out validation set. The top two motion artifacts in this figure are more severe (motion-corrupted image SSIM of 0.34 and 0.27, respectively) than the bottom two rows (SSIM of 0.4 and 0.58, respectively), suggesting that the performance of our model is comparable for severe and mild motion artifacts.

The mean SSIM in NCC-CycleGAN motion-corrected images increased significantly to 0.76 ± 0.06 from 0.43 ± 0.12 in the corresponding respiratory-induced motion-corrupted images (Figure 4a). The mean PSNR was also significantly improved to 24.92±2.42 from 20.18±3.14. This verifies the consistent performance of our NCC-CycleGAN model in correcting different degrees of respiratory motion artifacts.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate the feasibility of developing an unsupervised DL-based method for efficient automated retrospective kidney MRI motion correction. This study sets the foundation for future work to develop a DL-based method for correction of different types of complex nonlinear motion artifacts in kidney MRI.Acknowledgements

This work was conducted by the Australian Research Council Training Centre for Innovation in Biomedical Imaging Technology research and funded, in part, by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council (DP140103593 and IC170100035). Authors acknowledge the facilities and scientific and technical assistance of the National Imaging Facility, a National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) capability, at the Centre for Advanced Imaging, The University of Queensland. We also thank Aiman Al Najjar and Nicole Atcheson from the Centre for Advanced Imaging, The University of Queensland for helping with MR data acquisition.

References

1. Dillman JR, Tkach JA, Pedneker A, Trout AT. Quantitative abdominal magnetic resonance imaging in children-special considerations. Abdom Radiol (NY). Jul 1 2021;doi:10.1007/s00261-021-03191-9

2. Havsteen I, Ohlhues A, Madsen KH, Nybing JD, Christensen H, Christensen A. Are Movement Artifacts in Magnetic Resonance imaging a Real Problem?-A Narrative Review. Front Neurol. May 30 2017;8doi:ARTN 232

10.3389/fneur.2017.00232

3. Paling MR, Brookeman JR. Respiration Artifacts in Mr Imaging - Reduction by Breath Holding. J Comput Assist Tomo. Nov-Dec 1986;10(6):1080-1082. doi:Doi 10.1097/00004728-198611000-00046

4. Ehman RL, Mcnamara MT, Pallack M, Hricak H, Higgins CB. Magnetic-Resonance Imaging with Respiratory Gating - Techniques and Advantages. Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(6):1175-1182. doi:DOI 10.2214/ajr.143.6.1175

5. Fu ZW, Wang Y, Grimm RC, et al. Orbital navigator echoes for motion measurements in magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(5):746-753.

6. Tisdall MD, Hess AT, Reuter M, Meintjes EM, Fischl B, van der Kouwe AJ. Volumetric navigators for prospective motion correction and selective reacquisition in neuroanatomical MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(2):389-399.

7. Welch EB, Manduca A, Grimm RC, Ward HA, Jack Jr CR. Spherical navigator echoes for full 3D rigid body motion measurement in MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2002;47(1):32-41.

8. White N, Roddey C, Shankaranarayanan A, et al. PROMO: real‐time prospective motion correction in MRI using image‐based tracking. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;63(1):91-105.

9. Maclaren J, Herbst M, Speck O, Zaitsev M. Prospective motion correction in brain imaging: A review. Magn Reson Med. Mar 2013;69(3):621-636. doi:10.1002/mrm.24314

10. Gallichan D, Marques JP, Gruetter R. Retrospective correction of involuntary microscopic head movement using highly accelerated fat image navigators (3D FatNavs) at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(3):1030-1039.

11. Küstner T, Armanious K, Yang J, Yang B, Schick F, Gatidis S. Retrospective correction of motion‐affected MR images using deep learning frameworks. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82(4):1527-1540.

12. Atkinson D, Hill DL, Stoyle PN, et al. Automatic compensation of motion artifacts in MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;41(1):163-170.

13. Loktyushin A, Nickisch H, Pohmann R, Schölkopf B. Blind retrospective motion correction of MR images. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(6):1608-1618.

14. LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. nature. 2015;521(7553):436-444.

15. Havaei M, Davy A, Warde-Farley D, et al. Brain tumor segmentation with deep neural networks. Medical image analysis. 2017;35:18-31.

16. Lu D, Popuri K, Ding GW, Balachandar R, Beg MF. Multimodal and multiscale deep neural networks for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using structural MR and FDG-PET images. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):1-13.

17. Ravì D, Wong C, Deligianni F, et al. Deep learning for health informatics. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics. 2016;21(1):4-21.

18. Haskell MW, Cauley SF, Bilgic B, et al. Network accelerated motion estimation and reduction (NAMER): convolutional neural network guided retrospective motion correction using a separable motion model. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82(4):1452-1461.

19. Johnson PM, Drangova M. Conditional generative adversarial network for 3D rigid‐body motion correction in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82(3):901-910.

20. Pawar K, Chen Z, Shah NJ, Egan GF. Motion correction in MRI using deep convolutional neural network. 2018:

21. Pawar K, Chen Z, Shah NJ, Egan GF. Suppressing motion artefacts in MRI using an Inception‐ResNet network with motion simulation augmentation. NMR in Biomedicine. 2019:e4225.

22. Sommer K, Saalbach A, Brosch T, Hall C, Cross N, Andre J. Correction of motion artifacts using a multiscale fully convolutional neural network. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2020;41(3):416-423.

23. Tamada D, Kromrey ML, Ichikawa S, Onishi H, Motosugi U. Motion Artifact Reduction Using a Convolutional Neural Network for Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MR Imaging of the Liver. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2020;19(1):64-76. doi:10.2463/mrms.mp.2018-0156

24. Zhu J-Y, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. 2017:2223-2232.

Figures

Figure 1. Cycle-consistency GAN network structure. The Cycle-GAN network consists of two generators and two discriminators, each playing a role in updating the other three network components. The solid black arrows show a forward cycle from motion corrupted to motion free image translation and the dashed black arrows illustrate a backward cycle from motion free to motion corrupted image translation. In each image domain, the blue and red circles represent the real image and the synthesised image generated by the corresponding generator, respectively.