4913

Automated Motion Artifact Detection in Early Pediatric Diffusion MRI Using a Convolutional Neural Network

Jayse Merle Weaver1,2, Marissa DiPiero2,3, Patrik Goncalves Rodrigues2, Hassan Cordash2, and Douglas C Dean III1,2,4

1Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Neuroscience Training Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

1Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Neuroscience Training Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Artifacts, Quality Control

A three-dimensional convolutional neural network was trained to detect motion artifacts on a volume level for two pediatric diffusion MRI datasets acquired between 1 month and 3 years of age. Accuracies of 95% and 98% were achieved between the two datasets. Additionally, the effects of motion-corrupted volumes on quantitative parameter estimation was examined. Data was processed without quality control and with quality control performed by the neural network. DTI and NODDI metrics were calculated and compared between methods. Significant differences were found for both individual and group results.Introduction

DTI and NODDI are quantitative MRI techniques capable of probing microstructural changes using diffusion MRI (dMRI) data1,2. The metrics obtained from fitting the DTI and NODDI models provide sensitive markers for brain development and disorders but may be confounded by artifacts in the dMRI images, such as those from subject motion. Hence, quality control (QC) measures are needed to identify such motion and other artifacts from dMRI data to either correct or exclude these data from further analysis. The gold standard for QC of dMRI data, especially pediatric dMRI, is visual inspection and removing artifact-corrupted DWIs from further processing. However, this is time-consuming and prone to subjective error. Thus, automated QC is desired.Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been used to perform automated QC of dMRI data3,4,5,6,7,8. However, no prior works have performed automated QC using a CNN on pediatric dMRI in the age range of 1 month to 3 years, a period of life targeted in recent neuroimaging studies due to the rapid development of white matter9. In this work, we propose a 3D-CNN for detecting motion artifacts in dMRI data acquired during the first 3 years of life.

Methods

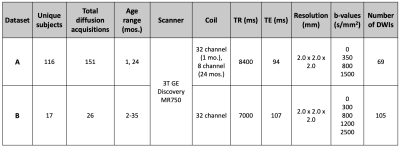

For this work, we used two datasets (Dataset A and B, Table 1) acquired with different acquisition parameters and on populations with different age ranges. Dataset A contains 151 dMRI datasets acquired at two time points, 1 and 24 months of age. Dataset B contains 26 dMRI datasets acquired between 2 and 35 months of age. All data were acquired during natural, non-sedated sleep.Dataset A was used to create the training and testing sets using an identical number of motion-corrupted and motion-free volumes. To prevent data leakage, training and testing sets were split by subject rather than volume. Dataset B served as an additional unseen testing set. All volumes were resized to a common size (128x128x70) and intensity normalized between 0 and 1.

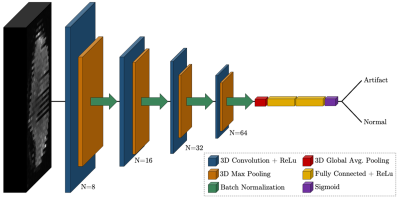

The 3D-CNN architecture was implemented in Python using Keras and Tensorflow. An overview of the network architecture is depicted in Figure 1. The network consists of four feature extraction blocks, with each block containing a 3D convolutional layer with an increasing number of filters, a kernel size of 3x3x3, and ReLU activation. Each convolutional layer is followed by a 3D max pooling layer with a pool size of 2 and batch normalization. The final output is flattened and passed to two fully connected layers with a total dropout rate of 50%. Lastly, a dense layer with 1 neuron and sigmoid activation is used for binary classification.

The network was trained with a batch size of 8, binary cross-entropy as the loss function, and the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-3 and learning rate decay of 0.01. K-fold cross-validation with k=4 was used to test the model’s dependence on the input data.

The model with the highest accuracy across both datasets was selected for use in a pre-processing and analysis pipeline developed by our lab. All one-month-old subjects in the testing dataset (n=24) were used for analysis. The pipeline was repeated three times for each subject with different QC methods: motion-corrupted volumes were identified by a human reader and removed (manual QC), identified by the neural network and removed (model QC), or not removed at all (no QC). The data were fit to the DTI model using the DIPY package10 and the NODDI model using the Dmipy toolbox11.

A study-specific template was created from FA maps using ANTs12. Corpus callosum and internal capsule ROIs were obtained from the JHU Neonate Atlas13. ROIs were then warped into each subject’s native space. FA, RD, and ICVF values were extracted using the ROIs, and intrasubject and group differences between QC methods were examined using t- and F-tests.

Results

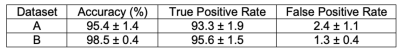

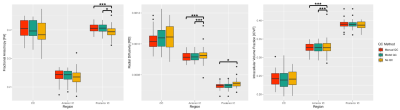

Mean accuracies of 95.4% and 98.5% were achieved on Datasets A and B, respectively (Table 2). Box plots displaying the mean FA, RD, and ICVF values for each region and QC method are shown in Figure 2. The F-tests revealed significant differences in the variances between QC methods. The results of individual t- and F-tests (Table 3) show significant differences in the mean of at least one quantitative measure for 19 of the 24 subjects.Discussion & Conclusion

While CNNs have been previously used to perform automated QC of diffusion data, no studies have trained and evaluated a network on data acquired from infants and toddlers. The proposed CNN identifies motion artifacts with an accuracy greater than 95%. Additionally, the removal of motion-corrupted volumes by either manual QC or neural network QC causes significant differences in a subset of DTI and NODDI metrics on an individual and group level.The proposed network performs binary classification focusing on detecting motion artifacts, the most common artifact when scanning young children during natural, non-sedated sleep. Future work will employ additional public datasets during network training to perform multi-label classification of several types of artifacts on a wider range of pediatric data.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank our research participants and their families who participated in this research as well as the dedicated research staff who made this work possible. This work was supported by grants P50 MH100031, 5R00 MH110596-05, and 1U01 DA055370-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health. Infrastructure support was also provided, in part, by grant U54 HD090256 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD, National Institutes of Health (Waisman Center).References

- Alexander, A. L., Lee, J. E., Lazar, M., & Field, A. S. (2007). Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 4(3), 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011

- Zhang, H., Schneider, T., Wheeler-Kingshott, C. A., & Alexander, D. C. (2012). NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. NeuroImage, 61(4), 1000–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.072

- Kelly, C., Pietsch, M., Counsell, S., & Tournier, J. D. (2017, April). Transfer learning and convolutional neural net fusion for motion artefact detection. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Honolulu, Hawaii (Vol. 3523).

- Graham, M. S., Drobnjak, I., & Zhang, H. (2018). A supervised learning approach for diffusion MRI quality control with minimal training data. NeuroImage, 178, 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.077

- Samani, Z. R., Alappatt, J. A., Parker, D., Ismail, A., & Verma, R. (2020). QC-Automator: Deep Learning-Based Automated Quality Control for Diffusion MR Images. Frontiers in neuroscience, 13, 1456. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01456

- Ahmad, A., Parker, D., Samani, Z. R., & Verma, R. (2021). 3D-QCNet--A pipeline for automated artifact detection in diffusion MRI images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.05285.

- Ettehadi, N., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Semanek, D., Guo, J., Posner, J., & Laine, A. F. (2021). Automatic Volumetric Quality Assessment of Diffusion MR Images via Convolutional Neural Network Classifiers. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference, 2021, 2756–2760. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9630834

- Ettehadi, N., Kashyap, P., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Semanek, D., Desai, K., Guo, J., Posner, J., & Laine, A. F. (2022). Automated Multiclass Artifact Detection in Diffusion MRI Volumes via 3D Residual Squeeze-and-Excitation Convolutional Neural Networks. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 16, 877326. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.877326

- Lebel, C., & Deoni, S. (2018). The development of brain white matter microstructure. NeuroImage, 182, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.097

- Garyfallidis, E., Brett, M., Amirbekian, B., Rokem, A., van der Walt, S., Descoteaux, M., Nimmo-Smith, I., & Dipy Contributors (2014). Dipy, a library for the analysis of diffusion MRI data. Frontiers in neuroinformatics, 8, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2014.00008

- Fick, R., Wassermann, D., & Deriche, R. (2019). The Dmipy Toolbox: Diffusion MRI Multi-Compartment Modeling and Microstructure Recovery Made Easy. Frontiers in neuroinformatics, 13, 64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2019.00064

- Avants, B. B., Tustison, N. J., Song, G., Cook, P. A., Klein, A., & Gee, J. C. (2011). A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. NeuroImage, 54(3), 2033–2044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025

- Oishi, K., Mori, S., Donohue, P. K., Ernst, T., Anderson, L., Buchthal, S., Faria, A., Jiang, H., Li, X., Miller, M. I., van Zijl, P. C., & Chang, L. (2011). Multi-contrast human neonatal brain atlas: application to normal neonate development analysis. NeuroImage, 56(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.051

Figures

Table 1:

Dataset details and acquisition

parameters. All exams used the same 3T scanner (Discovery MR 750, GE

Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and either an 8-channel (GE Healthcare) or a

32-channel (Nova Medical, Wakefield, MA) receive-only head coil. Dataset A was

used to create the training and testing dataset for the neural network, while

Dataset B was held as an unseen dataset for additional testing. All images were

acquired during natural, non-sedated sleep.

Figure 1:

Proposed convolutional neural network

architecture for the detection of motion artifacts in 3D diffusion MRI volumes

of size 128x128x70. The network consists of 4 blocks of 3D convolution

(N=#filters), 3D max pooling (pool=2), and batch normalization, followed by

flattening, dense layers with 50% total dropout, and a sigmoid layer for final

classification.

Table 2:

Neural network testing results. Mean and

standard deviations were calculated using four networks trained during k-folds

cross-validation. Dataset A was partitioned for both training and testing the

network, while Dataset B was used exclusively for testing.

Figure 2:

Box plots displaying comparisons between

QC processing pipelines for three quantitative measures (FA, RD, and ICVF) and

three brain regions (corpus callosum, anterior internal capsules, and exterior

internal capsules). F-test significance was defined as p < 0.05 (*) and p

< 0.0167 (***) following Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons.

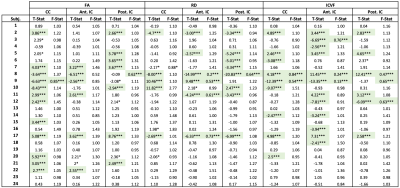

Table 3:

Paired t-

and F-test

results for individual subject ROIs comparing manual and neural network QC

methods for

three quantitative measures (FA, RD, and ICVF) and three brain regions (corpus

callosum, anterior internal capsules, and exterior internal capsules). Significance

was defined as p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.0167 (***, shaded) following

Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4913