4911

Automatic Fetal Orientation Detection Algorithm in Fetal MRI1Department of Electrical, Computer and Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Sciences, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Division of Neuroradiology, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Department of Diagnostic Imaging, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Department of Medical Imaging, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Science and Technology (iBEST), Toronto Metropolitan University and St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Convolutional Neural Networks, Fet-Net

Fetal orientation determines the mode of delivery. It is also important for sequence planning in fetal MRI. This abstract proposes Fet-Net, a deep-learning algorithm, which uses a novel convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture, to automatically detect fetal orientation from a 2-dimensional (2D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) slice. 6,120 2D MRI slices displaying vertex, breech, oblique and transverse fetal orientations were used for training, validation and testing. Fet-Net achieved an average accuracy and F1 score of 97.68%, and a loss of 0.06828. Fet-Net was able to detect and classify fetal orientation, which may serve to accelerate fetal MRI acquisition.Introduction

Fetal MR imaging has become increasingly important in the evaluation of complex fetal abnormalities in recent years and outperforms US in the detection of classification of many fetal pathologies1,2. According to the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine3, one of the key features to identify in all second and third trimester fetal imaging is fetal presentation, or the position of the fetus relative to specific maternal anatomical structures4. Diagnosing fetal orientation is important for the choice of delivery, but also for fetal MRI sequence planning5-7. To the best of our knowledge, no work has applied Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for fetal orientation detection. We aimed to establish and evaluate a CNN algorithm that automatically detects four fetal presentations - vertex (head down), breech (head up), oblique (diagonal) and transverse (sideways)4,8,9, and to compare this algorithm’s performance with that of other state-of-the-art CNN architectures, including VGG, ResNet, Xception and Inception.Methods

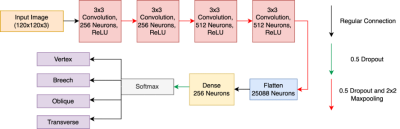

In this retrospective study, 144 T2-weighted coronal 3-dimensional (3D) fetal MRI datasets were included, each consisting of 56-112 2D slices. The spatial resolution of the images was either 512 x 512 or 256 x 256. The 3D fetal MRIs were acquired using a True Fast Imaging with Steady State Free Precession (TrueFISP) sequence at a field strength of 1.5T or 3T. Before training and testing, the fetal MRI datasets were labeled to perform supervised learning. Each 2D slice was classified based on fetal orientation, as shown in Figure 1. Of the 144 3D MRIs, 65 were vertex, 61 were breech, 11 were transverse, and seven were oblique. The fetal MRI datasets ranged in gestational age (GA) from 20+2 weeks to 38+1 weeks. Following data augmentation, each of the four labels consisted of 1,530 2D images, ridding the algorithm of any inherent biases towards one specific label over another. In total, 6,120 2D MRI slices were included in the dataset.The Fet-Net architecture consisted of seven layers. Four convolutional layers, each with a 2D convolutional filter component and a 2D 2x2 MaxPooling component, made up the feature extraction section of the architecture. Dropout rates of 0.5 were present across every layer of the network to help prevent overfitting. The end of the feature extraction component then fed into a neural network, which was composed of the fully connected layer consisting of 25,088 neurons, a hidden dense layer of 256 neurons, and a final layer for classification with four neurons for the four labels. The Fet-Net architecture, which follows a sequential CNN approach inspired by10 is illustrated in Figure 2.

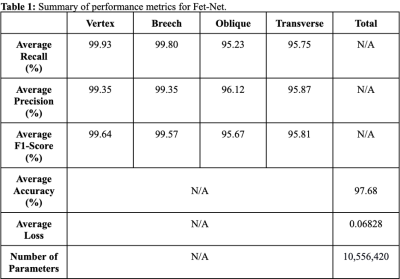

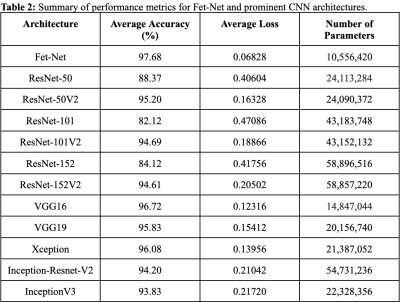

Accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score were used to analyze the performance of the trained model architecture. A 5-fold cross-validation experiment was performed to analyze the performance of the Fet-Net. The same dataset was used for training, validating and testing the VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, ResNet50-V2, ResNet101, ResNet101-V2, ResNet152, ResNet152-V2, Xception, Inception-Resnet-V2, and InceptionV3 architectures11-16.

Results

As shown in Tables 1-2, Fet-Net achieved a classification accuracy between 95.23% and 99.93%, depending on the label, resulting in an average accuracy of 97.68%. In comparison to all eleven prominent architectures, Fet-Net demonstrated the highest average accuracy and loss, despite having the fewest number of architectural parameters.Discussion

The convolutional neural network, Fet-Net, was able to accurately classify the fetal orientation of a 2D MRI slice as vertex, breech, oblique or transverse. A seven-layer CNN was constructed and tested on 6,120 images by way of 5-fold cross-validation. Fet-Net achieved an average accuracy and F1 score of 97.68%, and a loss of 0.06828. Precision and recall scores for each individual orientation were above 95.23%.The VGG16 architecture was the closest to Fet-Net in performance, but had a lower accuracy by 0.96%, and a greater loss by 0.05488. The most significant difference was seen with the ResNet101 architecture, which had a lower accuracy by 15.56%, and a greater loss by 0.40258. One-sided statistical ANOVA testing demonstrated that the differences in results between the novel Fet-Net architecture and those of VGG16 for accuracy and loss were significant (p<0.05). Since the VGG16 architecture was closest to Fet-Net in terms of performance, Fet-Net's architecture statistically outperformed all eleven prominent architectures. The precision and recall of Fet-Net for each individual label were superior to every other architecture, except for the precision of VGG16 for the transverse label and the recall of VGG16 for the oblique label by 0.3742% and 0.3936%, respectively. Furthermore, the reduced loss value of 0.06828 of Fet-Net is evidence of a predictive model that not only classifies more accurately, but is also more confident in its classifications.

Conclusion

In this experiment, a novel CNN architecture was designed to automatically detect fetal orientation from a 2D fetal MRI slice. The constructed Fet-Net architecture was a simpler network with fewer layers and parameters; yet, performed better on the 6,120 2D image slices of the dataset relative to eleven other prominent classification architectures. The automated detection of fetal orientation may help in sequence planning for fetal MRI acquisition, potentially making fetal MRI acquisition faster and less operator dependent.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Y.-S. Sohn, M.-J. Kim, J.-Y. Kwon, Y.-H. Kim, and Y.-W. Park, “The Usefulness of Fetal MRI for Prenatal Diagnosis,” Yonsei Med J, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 671–677, Aug. 2007, doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.4.671.

2. I. Pimentel, J. Costa, and Ó. Tavares, “Fetal MRI vs. fetal ultrasound in the diagnosis of pathologies of the central nervous system,” European Journal of Public Health, vol. 31, no. Supplement_2, p. ckab120.079, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckab120.079.

3. “AIUM–ACR–ACOG–SMFM–SRU Practice Parameter for the Performance of Standard Diagnostic Obstetric Ultrasound Examinations,” Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, vol. 37, no. 11, pp. E13–E24, 2018, doi: 10.1002/jum.14831.

4. A. G. D. of Health, “Fetal presentation,” Australian Government Department of Health, Jun. 21, 2018. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/pregnancy-care-guidelines/part-j-clinical-assessments-in-late-pregnancy/fetal-presentation (accessed Dec. 03, 2021).

5. M. E. Hannah, W. J. Hannah, S. A. Hewson, E. D. Hodnett, S. Saigal, and A. R. Willan, “Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial,” The Lancet, vol. 356, no. 9239, pp. 1375–1383, Oct. 2000, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02840-3.

6. J. Lyons et al., “Delivery of Breech Presentation at Term Gestation in Canada, 2003–2011,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 125, no. 5, pp. 1153–1161, May 2015, doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000794.

7. A. Herbst, “Term breech delivery in Sweden: mortality relative to fetal presentation and planned mode of delivery,” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, vol. 84, no. 6, pp. 593–601, Jan. 2005, doi: 10.1080/j.0001-6349.2005.00852.x.

8. M. J. Hourihane, “Etiology and Management of Oblique Lie,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 512–519, Oct. 1968.

9. G. D. V. Hankins, T. L. Hammond, R. R. Snyder, and L. C. Gilstrap, “Transverse Lie,” Am J Perinatol, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 66–70, Jan. 1990, doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999449.

10. K. F. Haque and A. Abdelgawad, “A Deep Learning Approach to Detect COVID-19 Patients from Chest X-ray Images,” AI, vol. 1, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.3390/ai1030027.

11. K. Team, “Keras documentation: VGG16 and VGG19.” https://keras.io/api/applications/vgg/ (accessed Nov. 08, 2022).

12. K. Team, “Keras documentation: ResNet and ResNetV2.” https://keras.io/api/applications/resnet/#resnet-and-resnetv2 (accessed Nov. 08, 2022).

13. K. Team, “Keras documentation: Xception.” https://keras.io/api/applications/xception/ (accessed Nov. 08, 2022).

14. K. Team, “Keras documentation: InceptionResNetV2.” https://keras.io/api/applications/inceptionresnetv2/ (accessed Nov. 08, 2022).

15. K. Team, “Keras documentation: InceptionV3.” https://keras.io/api/applications/inceptionv3/ (accessed Nov. 08, 2022).

16. K. Team, “Keras documentation: Keras Applications.” https://keras.io/api/applications/ (accessed Nov. 08, 2022).

Figures